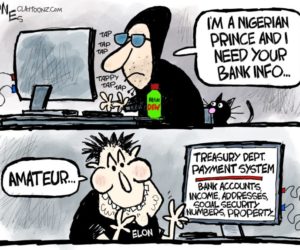

A World Health Organization (WHO) conference on smoking control has not endorsed industry arguments that new smokeless nicotine products are better alternatives to smoking traditional cigarettes.

The clash paves the way for the next great multi-billion-dollar squabble between WHO and industry. This time it is on whether marketing high technology smokeless cigarettes, including electronic products, should face fewer hurdles than currently in place for real tobacco cigarettes.

The WHO Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC), a treaty with 148 Contracting Parties, significantly tightened anti-smoking measures this month and rejected tobacco and vaping industry efforts to influence its work.

It has a powerful ally in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is determined to keep smokeless nicotine products away from minors and young people because they can be addictive.

The conference agreed new strategies to prevent “further interference by tobacco industry in public health policies”. Governments also reaffirmed their resolve to protect their anti-smoking policies “from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry,” a FCTC statement said.

“More than ever, we need to stay the course and strengthen our commitment to ensure that FCTC efforts to protect and promote public health and sustainable development are not hijacked by the tobacco industry,” the secretariat’s chief Vera Luiza da Costa e Silva said.

“We must yield no ground to the tobacco industry… With astronomical budgets, the tobacco industry continues its furious efforts to undermine the implementation of our treaty,” she warned.

This strong anti-industry stance leaves less room for tobacco industry arguments that their new electronic products are less harmful for the more than one billion people worldwide who still crave nicotine.

Announcing tougher measures to prevent sales of smokeless electronic products to young people, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said last month, “We cannot allow a whole new generation to become addicted to nicotine”.

“We see clear signs that youth use of electronic cigarettes has reached an epidemic proportion, and we must adjust certain aspects of our comprehensive strategy to stem this clear and present danger.”

Industry advocates face an uphill struggle to gain wide acceptance from WHO and national regulatory authorities of their contention that their new smokeless and electronic products are efficient methods of harm reduction. Or that they are better alternatives for those who want to quit smoking traditional cigarettes but are unable to give up on nicotine.

Both WHO and USFDA favor measures to promote the potential of e-cigarettes to help adult smokers move away from combustible cigarettes. But not at the expense of young people who are being enticed by new smokeless products that deliver nicotine masked in sweet-tasting compounds.

Major traditional tobacco products companies, including Philip Morris International (PMI) and Imperial Tobacco, insist that their new smoke-free products developed after billions of dollars in research are better alternatives to smoking.

Full page newspaper advertisements quote PMI CEO André Calantzopoulos saying, “I am committed to a smoke-free future. And a conversation about how to achieve it together”.

That smoke-free future involves a shift away from traditional cigarettes to vaping, which uses new high-tech products that satisfy nicotine-related cravings without producing the smoke that causes negative health effects. The argument is that smoking’s harmful health effects are not caused by tobacco but by the smoke inhaled.

New innovative products that heat the tobacco but do not burn it are racing to conquer the world’s smokers. Their producers would be delighted if health authorities like WHO were to declare them less harmful and treat them separately from the blanket bans on smoking in public spaces and draconian curbs on advertising, including fear-provoking visuals placed on traditional cigarette packages to discourage smoking.

But their argument is strongly contested by anti-smoking activists and is being handled with caution by the WHO, the European Commission, USFDA and many national regulatory authorities.

Authorities await more convincing scientific studies conducted by independent researchers rather than those funded by companies on medium and longer-term health impacts.

A WHO report estimated that most adopters of vaping do so because they have quit smoking, and 40 percent are trying to give up. But vast new markets await smoke-free products because one-third of smokers have never tried a vaping device.

Inopportunely for FCTC, many more smokers believe that vaping is less harmful than smoking. This is the breach through which the vaping industry expects to expand sales and market shares.

Potential market shares are so enticing that Calantzopoulos told a New York conference PMI (formerly a tobacco major) is radically transforming as a company “to deliver a future without cigarettes”. Six million adults in 40 countries had already switched “to our heated tobacco product.”

WHO finds the harm reduction aspect of vaping hard to refute because of insufficient medium to long term research on its health effects. But there is growing concern that the nicotine contained in heated tobacco and other electronic products worsens addiction.