The Roman General Broke One Law and Was Met With War. The U.S. President Is Breaking Laws Left and Right—Without Major Resistance

By Michele Renee Salzman

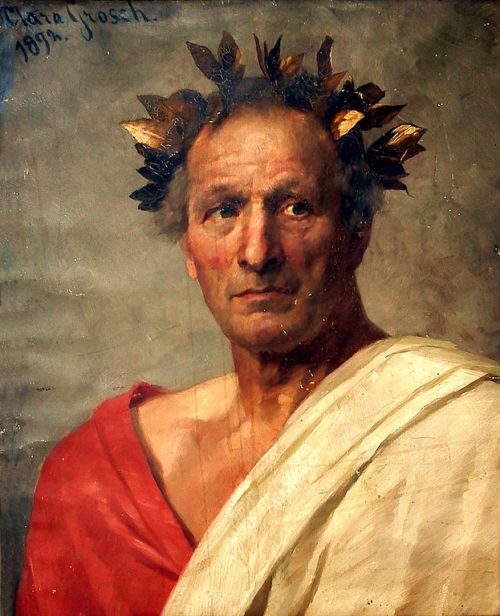

Commentators love to compare Donald Trump’s norm-breaking ways to Julius Caesar’s momentous decision to “cross the Rubicon” in 49 B.C.E. By leading his troops over the Rubicon River and into Italy to stand for election in Rome, Caesar defied Roman law. The outrage that followed set the stage for the civil wars that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the birth of the Roman Empire. The Rubicon comparison appeals to pundits because it recognizes the destructive impact of a populist leader who willingly breaks the law to gain power.

But the analogy ultimately falls short because Trump’s actions are more far-reaching than Caesar’s—and because they have met less resistance.

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon, his goal was specific and limited. Caesar had no desire to remake the republic nor to destroy the way Roman politics worked. He simply wanted to bring his army with him to run for election for consul, the highest executive position in the state—a position voted on yearly, and one he had served before, in 59 B.C.E. Since then, Caesar’s military feats, daring exploits, and unparalleled leadership of his legions in Gaul (now modern France), which he advertised in his Commentaries, had made him tremendously popular in Rome and very wealthy. Now, he was ready to return to Rome, triumphantly.

According to the law, he had to give up his command and disband his troops before entering Rome. This requirement was a legacy of earlier civil wars that had unfolded in the 80s B.C.E., when the popular generals Marius and Sulla marched on Rome to force the senate to grant them military commands. But Caesar’s troops, who worshipped him, were a crucial source of his strength. Without them at his side, the senate was likely to bring him up on charges for his misuse of funds and for his undertaking military actions in Gaul without senatorial permission. In such a scenario, he could have been exiled for his success.

So, Caesar found supporters in Rome: the 10 elected representatives of the people known as Tribunes of the Plebs. They put forth a law to allow him to run for office without giving up his command. Most senators opposed this request, believing such a compromise would undermine the state and greatly empower Caesar.

They were right. After Caesar learned that the Tribunes had failed, he tried once more to negotiate, offering to put down his arms if the senate took away command from the current consul, Pompey. The senate refused and declared Caesar a public enemy. They asked Pompey—a former commander himself—to raise an army to defend the state. Only then did Caesar cross the Rubicon River, entering Italy near Ravenna on January 10, 49 B.C.E. Caesar’s men followed their general, even if it meant civil war against their fellow citizens. Some may have believed Caesar’s claim that he was defending not just his honor, as the Roman biographer Suetonius tells us, but that of the tribunes and people of Rome, freeing the republic from the tyranny of the senate. But he also knew what was coming: “The die is cast,” he is alleged to have said, as he crossed the Rubicon.

The battles that embroiled the Mediterranean world for the next five years pitted Caesar and his troops against the remnants of Roman republican forces in Greece, Egypt, North Africa, Spain, and Italy.

But when he returned to Rome, first in 48 B.C.E., he had the senate name him dictator, a position that traditionally endowed temporary emergency powers. He initiated a stunning number of rapid reforms designed to “fix” the state. (Some were needed, like setting a calendar of 365 days, the same one we use today.) Ultimately, Caesar achieved victory. The senate—or at least those who survived and were granted clemency or who were newly appointed—honored Caesar in February 44 B.C.E. with a new title, dictator perpetuus or “dictator forever,” an unprecedented power. A month later, 60 senators joined in a plot to kill Caesar, stabbing him to death on the Ides of March.

Once Caesar was dead, the senate reconvened. They believed they could simply return the republic to what it had been before, but a new round of civil wars followed, ending with the emergence of Rome’s first emperor, Caesar’s great-nephew Octavian, who took the name Augustus, “Revered One.” With Augustus’ ascendance, the republic died, even as Augustus claimed to have restored it. But for historians, Caesar’s crossing the Rubicon, more than 20 years earlier, was the critical turning point.

Both Caesar and Trump were populists who spoke and behaved brashly, upending established norms and steering their followers in radically new directions. Politicians and citizens alike viewed both men as acting illegally to bring their respective, powerful republics to crisis. Caesar’s actions launched 500 years of imperial rule in the west. Trump’s actions, many argue, will herald an end to the post-World War II international order, and threaten American futures at home.

But in crucial ways, the situations are not the same—and it has as much to do with Trump as it does with his opponents in Congress and the courts. Trump has crossed the Rubicon without any attempts to negotiate with the U.S. legislature—and we don’t yet see any sustained, effective opposition to his illegal actions in the Senate or House of Representatives. In 44 B.C.E, the Roman Senate acted to uphold the law—and as a result, the senate continued to play a key role in reshaping the government of Rome in future centuries. Emperors worked with senators, relying on them to govern provinces and administer the state.

Trump’s use of executive orders is aimed at undermining the role of the Congress in government. And Congressional opposition is disorganized, internally divided, and virtually leaderless. A closer analog to the Roman Senate might be the U.S. courts, though it is not yet clear that Trump will abide by judicial decisions, nor that the courts will uphold pre-existing limits on presidential power.

Unlike Caesar’s limited goals in 49 B.C.E, Trump desires to bring widespread change to our republic—overturning everything from decades of foreign policy and lawfully constituted federal agencies to medical research, education, and the law.

To effectively preserve our republic, collective action and protest must be louder and more organized. It may not be too late for the U.S. Congress—and all of us—to stand up for the fundamentals of our democracy, the rights of federal workers and migrants, and the health of people at home and abroad. Roman senators—Pompey, Cato, Brutus, and Cassius—were willing to stand up to Caesar’s autocracy. But only future historians looking back will be able to determine if elected officials and people who actively oppose Trump today will be more successful in preserving our republic.

Michele Renee Salzman is a historian at the University of California, Riverside, and the author, most recently, of The ‘Falls’ of Rome: Crises, Resilience and Resurgence in Late Antiquity. This was written for Zócalo Public Square.