Mobile applications might provide a new business model for some artists, according to one of my students who has been researching the music industry this quarter. Last month, for example, the Presidents of the United States of America released an iPhone application containing four of their albums, plus rarities, live tracks and demos. The cost? $3.

Because the songs are streamed from the application, this distribution method should not cut into MP3 sales. That’s an important observation. At Gnomedex three years ago, Dave Dederer described how the band made as much as 80 percent of their revenue from the iTunes store.

Today I read in Fierce Mobile Content that Matt Groening’s long-running (22 years) comic Life In Hell will soon vanish from the pages of the LA Weekly. Jason Ankeny goes on to argue … you guessed it … that Life In Hell and other comics would be “natural on a Kindle or on an iPhone.” And it’s not just because these two devices offer a revenue model that the open web does not:

[T]he late, great Charles Schulz conceived Peanuts in a four-panel format that could be arranged horizontally, vertically or even as a square, all dependent on the needs of the newspapers that published it–by extension, an entire strip could fit horizontally across an iPhone screen, or as a square on a Kindle screen, or even as a panel-by-panel slideshow optimized for a smaller, more basic handset, and still remain true to Schulz’s original vision.

Moreover, a comic strip can offer a complete and satisfying experience whether you read just one strip or several weeks’ worth at one time–after all, the strips were written and drawn for readers to enjoy on a daily basis, but taken in larger chunks, the best comics offer extended storylines and levels of thematic depth as compelling as any more traditional narrative.

Here’s where I start to get nervous.

Digital Goods and Public Goods

I understand why content creators would gravitate to a proprietary, closed distribution platform. That platform provides the scarcity and exclusivity needed to make money. That’s because these platforms transform the digital good into one that is both “rival” and “excludable”. In their “native” digital state, these goods have the characteristics of public goods — they aren’t rival (two of us can consume them at the same time without interfering with the other person’s experience) and they aren’t excludable (the content owner cannot prevent us from consuming their good). That’s why public goods are financed by “the public”! Think most roads, police and first departments, lighthouses.

However, what has made the web a wild and wonderful place has been its disruption of proprietary information systems. Web standards and open systems are preconditions (along with ubiquitous connectivity) for our ability to “work in the cloud” regardless of our computer’s operating system or installed browser software. As Tim Berners-Lee said in 1996:

Anyone who slaps a ‘this page is best viewed with Browser X’ label on a Web page appears to be yearning for the bad old days, before the Web, when you had very little chance of reading a document written on another computer, another word processor, or another network.

However, cultural objects — music, television, non-financial news — are being hard-pressed to survive in the limited revenue space that is the open web.

Transitions are not pleasant for those in their midst. Ask (hypothetically) the nation’s buggy makers as the automobile became the vehicle of choice in America. In 1937, Time magazine reported (yes, it’s online and free to access – making my point about public goods) that there were “only 14 buggy-makers left in the U. S.” Yet in 1855, there had been 13 “carriage makers” in one small town alone, Mifflinburg, PA. Mifflinburg became “known as Buggy Town because its buggy makers produced more horse-drawn vehicles per capita than any other town in the state.” Eventually, all but one firm in Mifflinburg closed its doors; the remaining firm shifted to making automobile bodies, but it, too, shuttered its facilities in 1940.

The changes that we are undergoing in today’s market for information goods are no less wrenching or socially transformative than those faced by buggy makers in the early days of the automobile.

Who Owns The Network?

However, there’s one more wrinkle in today’s story. We access the open internet through a network of publicly and privately owned systems. In the United States, the pricing system — at least for home access — is principally an all-you-can-eat buffet. The size of the buffet may differ (think size as access speed), but in the main there are no limits on how much you can eat (download or upload).

The iPhone and Kindle data networks are different from the open internet; these networks are proprietary and closed. The Kindle currently has limited access to the internet, period. The iPhone accesses the internet via a metered, privately owned system (the “phone company”).

In the U.S. this market — mobile device internet access — has an oligopolistic structure, meaning that there are only a handful of companies, which translates to limited competition. Phone companies, of course, want to turn their oligopolies into monopolies; monopolies can make more money. Thus, AT&T negotiates a contract as the exclusive “phone company” for the iPhone. Finally, mobile telephony is not regulated in the same manner as landlines; mobile phone companies can charge what the market “will bear” without regulation, whereas landline fees are regulated.

Having our daily comics or news come to us courtesy of our mobile device would not be unlike having our “television” delivered via the cable company. But in this model, what would be the equivalent of the broadcast networks, the content that comes “over the air” (analogous to the open internet model)? Smart phones — and their data plans — are expensive. Newspapers and broadcast TV are relatively cheap (and the newspapers are available at the library).

Moving back to the automobile analogy for a moment: most roads in the U.S. (the automobile network) are publicly owned. Most have no fee for use. I believe that information networks are no less integral to the long-term economic viability of this country; however, most of them require a direct payment for access. (Roads have indirect fees: gasoline taxes and licensing fees, for example.)

Possible Solution For Public Service News

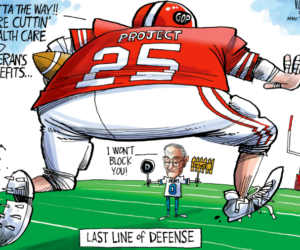

I care far less about the pay-to-view model implicit in iPhone or Kindle access to digital content when that content is entertainment (e.g., cultural objects like music) than I do when the content is essential to a functional and viable democracy (e.g., political news). My fear is that the latter is the one that will be hard-pressed to find a revenue source if it becomes totally unbundled from an artifact like the newspaper.

I don’t see the mobile model working for general news unless the content is licensed to the mobile phone company. Unfortunately, I can see this model working, at least for an elite audience. The result, I fear, would be a return to the information world of the 1980s, when the only way to access news was through a subscription* or a visit to the library. This model leads to oligopolistic information markets and reduced access to multiple points of view.

Perhaps the government could provide tax incentives for news organizations to provide “public service” information on the web, free-for-all; this open access model would be similar to broadcast TV. The news organizations would not be “licensed” (like broadcasters) but audited, perhaps, to determine the degree of tax break.

These news organizations could be hyperlocal websites or mega-corporations. Size and scope does not matter. The key, in my mind, is the quantity (ratio) of public service journalism. This is not the daily sports report, but it could be an investigation into insider gambling by an athlete or sports team owner. This is not Brittany’s latest adventures, but it could be an investigation into how celebrities are treated differently by the court system, when compared to non-celebrities (drugs, DUI, et.). This is not Peanuts, but it could be Cagle or Horsey. This is reporting on local school boards, governor task forces, public utility district meetings, city council meetings.

There is precedent: broadcast licenses (radio, TV) include a public service clause. I’m arguing that providing “free” access to public service journalism is equally important and a logical extension of that public service commitment.

We have to move quickly, if this “tax relief” model is to become viable. Newspaper organizations are teetering – all because of the loss of historical revenue models (classified ads lost to CraigsList and eBay); some because of self-inflicted wounds (too much debt, not “tending to knitting” as Tom Peters would say); and some because of misplaced shareholder priorities (an expectation of monopoly rents when the monopoly has vanished).

What have I missed?

* I’m old; I have dead-tree subscriptions to The Seattle Times, Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Harper’s, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and The Week. I have online-only subscriptions to Salon and The Financial Times. No, I don’t want to sum the annual subscription fees!

This article first appeared at WiredPen

Known for gnawing at complex questions like a terrier with a bone. Digital evangelist, writer, teacher. Transplanted Southerner; teach newbies to ride motorcycles. @kegill (Twitter and Mastodon.social); wiredpen.com