by John L. Micek

Where do we go next? What do we do now?

Those are the questions I found myself asking after I spoke to a panel of gun violence reduction activists this week. It was two nights after the murders in Boulder, a week after the rampage in Atlanta, and hours after the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee played out a drama so reliably scripted that it felt like even the players involved knew they were playing a role.

Even over Zoom, in the early hours of the evening, the frustration among my fellow panelists was palpable. I couldn’t see the slumped shoulders, but I could certainly feel them. There were some deep breaths. And a bit of gallows humor before these heroically dedicated volunteers – and they were all volunteers – plucked themselves up, and set about the endless work of trying to make a difference.

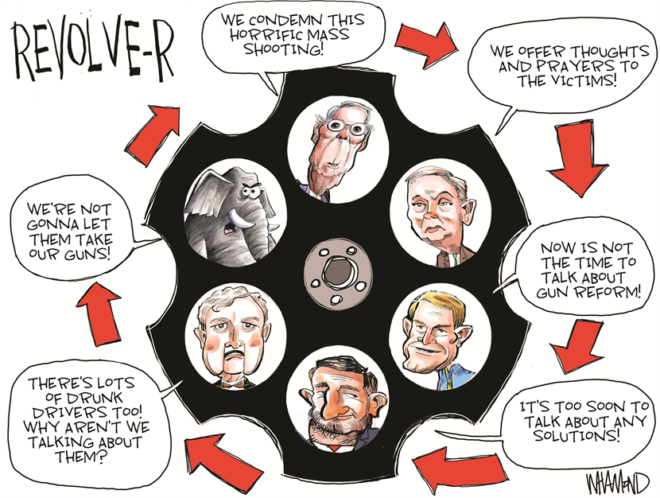

After every mass shooting – and they continued during the pandemic, even if you didn’t necessarily hear about them – our policy debate unfolds exactly the same way.

Gun violence reduction advocates in Washington D.C. and in state capitals across the land push for action. Opponents pretend to be horrified at the politicization of the issue, hollowly complain that it’s too soon to be talking about such things, and then nothing happens.

And the numbers are staggering. According to data compiled by the Gun Violence Archive, nearly 20,000 Americans lost their lives to gun violence last year, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. A further 24,000 died by suicide with a gun. It was the deadliest year in at least two decades, and it came on top of the catastrophic toll of the more than half-million we lost to the pandemic.

The accused shooter in Boulder allegedly carried out his murderous spree that claimed the lives of 10 people, including one police officer, with a weapon that was legally a pistol, but resembled a semi-automatic AR-15 rifle, the Washington Post reported.

City officials in Boulder had previously banned assault-style weapons until a judge struck down the ordinance weeks before the shooting.

In his ruling, Judge Andrew Hartman determined that “only Colorado state (or federal) law can prohibit the possession, sale, and transfer of assault weapons and large capacity magazines,” Colorado Newsline, reported.

The people of Boulder moved on their own because their state lawmakers and their elected representatives in Washington wouldn’t do it for them.

Where do we go next? What do we do now?

The answer is staring us in the face.

We ban assault weapons. Every last damn one of them. They’re the weapon of choice for mass murderers. They exist only to kill as quickly and efficiently as possible. The only people with a right to one are law enforcement and the military. I don’t need one. You don’t need one either.

After all, the United States had an assault weapons ban from 1994 to 2004. And it worked, as my friend and colleague John A. Tures, a political science professor at LaGrange College just an hour from Atlanta, recently wrote.

“From 2005 to 2021, there were an average of 5.1176 mass shootings per year, far more than the 1.6 from the [ban] years, and our year isn’t over yet,” Tures wrote. “And yes, the difference in means was statistically significant. Lumping the non-ban years with the ban years shows more mass shootings, on average, per year, during the years without an assault weapons ban, than during the years with [a ban].”

On Tuesday, President Joe Biden called on the Senate to act on two previously approved House bills tightening background checks and eliminating the so-called “Charleston Loophole,” which allows the sale of a gun to continue even if a background check is not finished if three business days have passed.

Biden told lawmakers he knows Congress can pass an assault weapons ban, observing that “I got that done when I was a senator. It passed, it was the law for the longest time. And it brought down these mass killings.”

Biden also made similar promises during his campaign, when he pledged to ban the sale of automatic weapons and high capacity magazines. He also said he’d implement a program for owners of semi-automatics to either sell them to the government or register their weapons under the National Firearms Act.

During a news conference in Pennsylvania earlier this week, the Rev. Bob Birch, who ministered to congregations in two communities shattered by gun violence – Newtown, Conn., and Nickel Mines, Pa. – argued the moral case for action.

“All of those killed were my neighbors. I cannot be a neighbor to those killed and their families, if I do not seek justice,” he said. “If I am to follow the way of Christ … I must work to end the cycle of hurting.”

That’s the moral test our lawmakers have faced and failed again and again. Given the opportunity to end the cycle of hurting, they have chosen not to act.

What do we now? Where do we go next? We know the answer. It’s been there all along.

Copyright 2021 John L. Micek, distributed by Cagle Cartoons newspaper syndicate. An award-winning political journalist, John L. Micek is Editor-in-Chief of The Pennsylvania Capital-Star in Harrisburg, Pa. Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @ByJohnLMicek.