One of my early jobs in the military was to manage the operation and maintenance of a computer.

Younger generations enjoying the reliability, speed and power of a laptop computer may rightly ask, what is there to maintain about a computer? Doesn’t one just buy another one when the old one crashes?

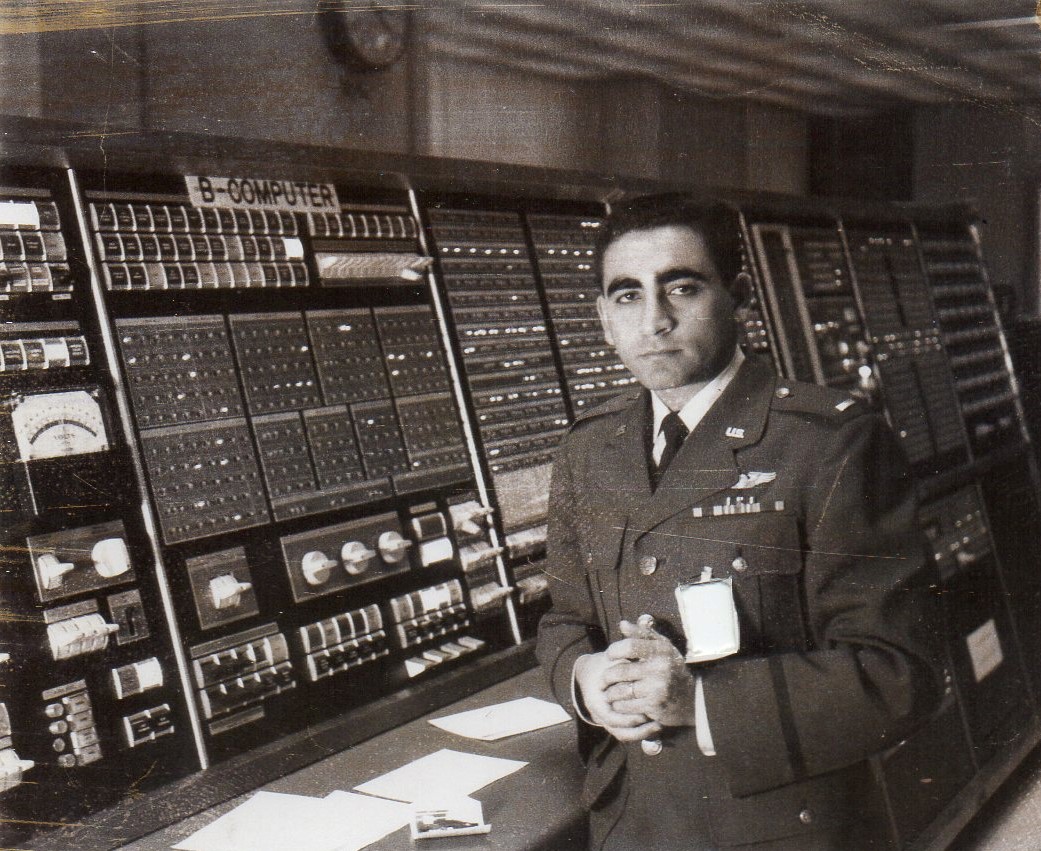

Well, let me tell you about “my” computer. Even better, let me give you a tour of the computer, just as I used to do at an Air Force SAGE (“semi-automatic ground environment”) air defense sector in the early 60s.

But first, let me explain the mission of an air defense sector.

During the Cold War, the threat of a Soviet “air-breathing” (manned bomber) attack on the United States was considered real. (On a couple of occasions, just short of “imminent.”) The mission of an air defense sector (there were 24 of them in the U.S.), with is computers, radar and communication systems, was to detect, identify, track, and guide weapons and fighter aircraft to intercept and, if necessary, destroy any hostile Soviet aircraft approaching the U.S.

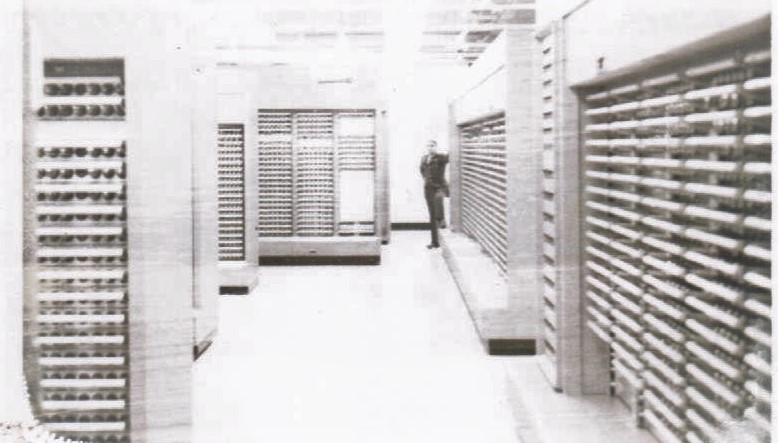

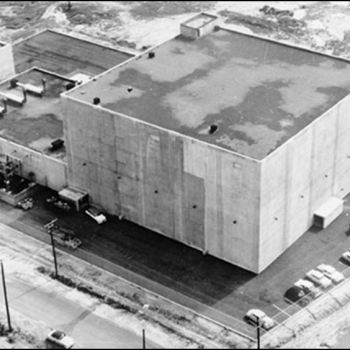

Processing the radar data and other inputs and providing the scores of personnel (surveillance and identification officers, weapons controllers, etc.) the information with which to perform the mission, was an enormous, 275-ton, vacuum tube (50,000 of them) computer occupying over ½ acre of floor space in a four-story concrete “blockhouse” with a total of 3.5 acres of floor space (below).

While, today, we plug our laptop computer into a 120-volt wall socket, the air defense computer’s power was provided by huge diesel generators that delivered enough electricity to power a small town and, since 50,000 vacuum tubes and other electronics generate an awful amount of heat, there was an air conditioning system big enough, you guessed it, to cool a small town. Both located in an adjacent facility.

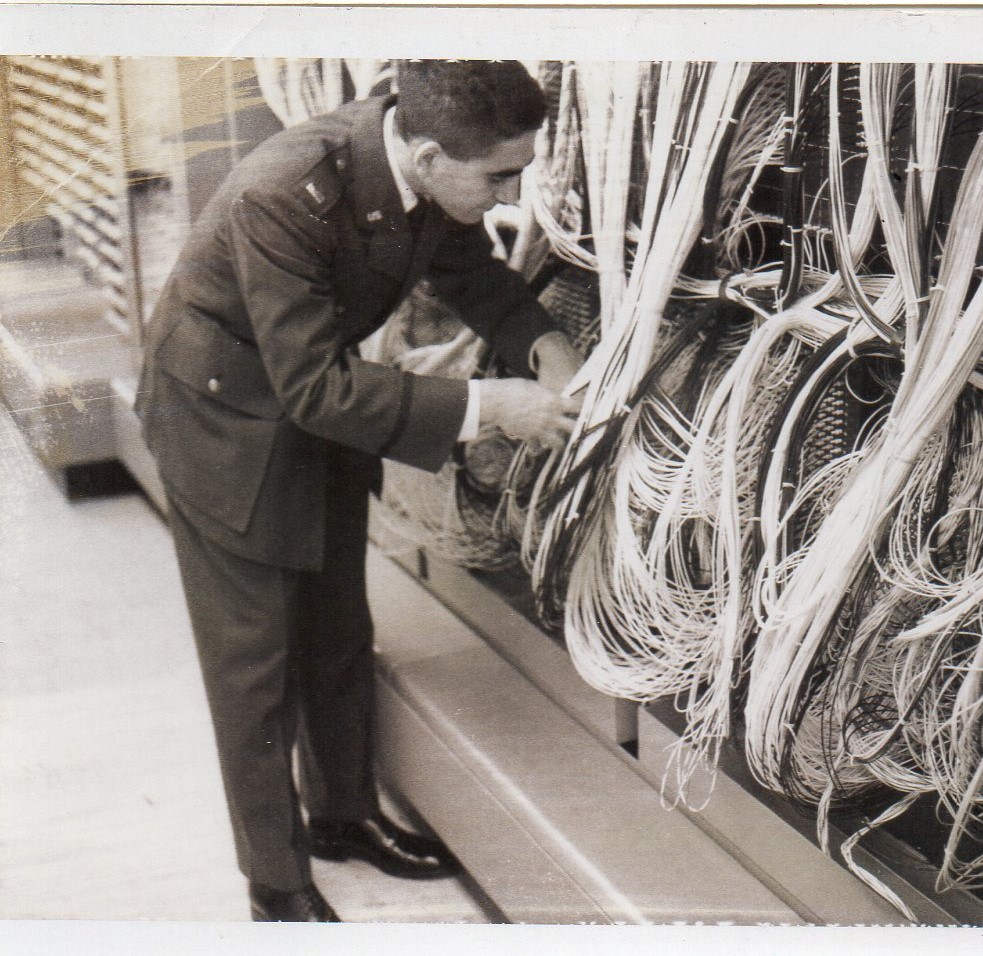

And did I mention the miles of wires and cables connecting everything together? (below)

Or the “magnetic drum” storage devices, each weighing 450 pounds whirling at 3600 rpm – what is now the miniscule “hard drive” in your laptop? How about the dozen 8-ft tall magnetic tape drives lined up along a wall.

The scores of 10-ft tall cabinets, each one containing a ”part” of the computer — such as a “register,” an “adder,” or a “memory” — were spread out over the ½ acre of floor space.

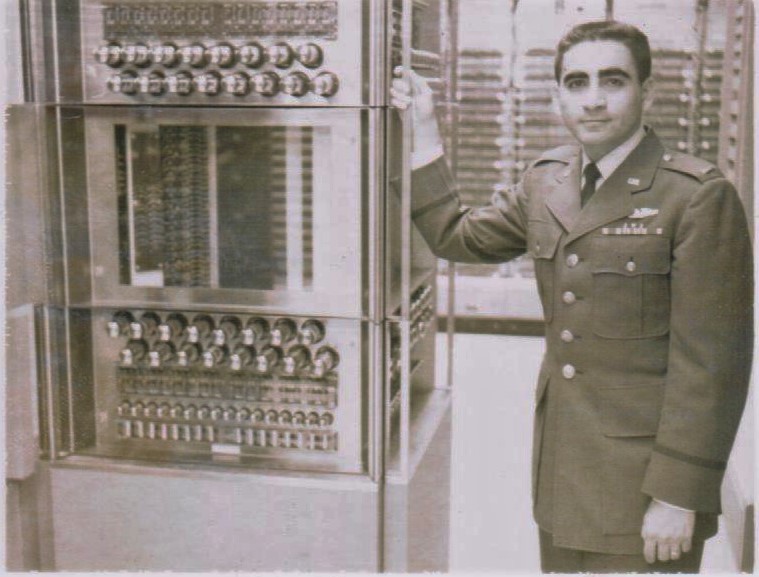

During the tours, I would proudly point to one of the “magnetic ferrite-core memories.” The one shown below stored 4,096 32-bit words and was called “Little Memory.”

The other one, “Big Memory,” stored an “amazing” 65,536 words. Compare that to a typical laptop’s storage capacity one billion times larger and a speed faster by nearly an equal factor all contained in a device no larger than a magazine, and almost as thin.

But back to the “operation and maintenance” of the air defense computer.

The scientists and engineers who designed the AN/FSQ-7 computer (that was the military “nomenclature”) determined at a very early stage that, with the state of the electronics technology at the time, there would be a “fatal” or “catastrophic” failure every few minutes. That would not do for such a critical military system.

Thus, they developed a dual-redundant computer system (two computers), where one – the “active system” — would be running the air defense program while the “standby system” was being maintained.

Part of the maintenance consisted of an ingenuous “marginal checking software system” that systematically varied the voltages to the vacuum tubes, inducing failures in weak components. In effect anticipating failures before they occurred, thus allowing technicians to replace marginal components before they actually failed.

That was the only way to achieve the 99% reliability absolutely necessary for such a critical military function.

But it came at a cost.

It took three shifts of 20 technicians each to keep this monster running 24/7.

Each system cost approximately $128 million in today’s dollars and the entire project is estimated to have cost between $80 and $120 billion in today’s dollars, exceeding the cost of the Manhattan Project.

Although, in some respects, it is like comparing apples to oranges, today’s typical laptop computer with speed, capacity and reliability one million times better costs around $500.

So, next time you are ready to throw your laptop out of the window because of a minor hiccup, think of the amazing power you hold in your hands, all for “peanuts.”

But also pause a moment to think of the brilliant scientists, engineers and programmers from MIT’s Lincoln Labs, MITRE, RAND and the System Development Corporation, IBM and others who made the impossible possible.