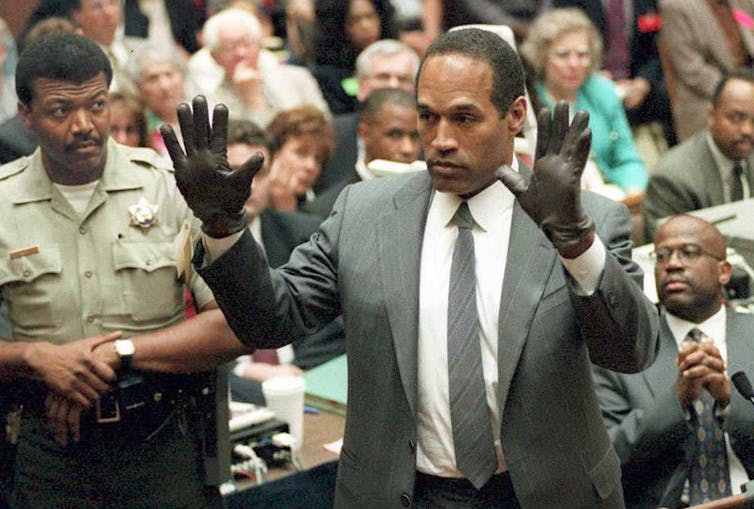

POO/AFP via Getty Images

Frankie Bailey, University at Albany, State University of New York

With the death of O.J. Simpson, I can’t help but wonder whether the media has learned any lessons from its coverage of his trial, in which the ex-football star was acquitted of murdering his ex-wife and her friend.

In many ways, the “trial of the century” brought out some of the media’s worst impulses.

As criminologist Gregg Barak explained, the O.J. Simpson case was a true “spectacle” – essentially a nine-month live news broadcast. At the same time, because of Simpson’s celebrity, the case was being followed as popular culture.

Of course, crimes have always attracted morbid interest, generating media attention and inspiring true-crime narratives.

But since the late 20th century, this has occurred more often – sometimes even before a trial has ended. The lines between news and entertainment have become increasingly blurred – what criminologist Ray Surette calls “infotainment” – with race, class and the quest for ratings influencing which crimes get covered and how they get portrayed.

Trial by media

Whenever I teach the O.J. Simpson trial in my criminal justice classes, I bring up a late-19th century murder case involving a white, upperclass woman named Lizzie Borden.

Both Simpson and Borden were accused of double murder – and both of their trials became a media circus.

In August 1892, Andrew Borden, a wealthy businessman, and Abby, his second wife, were hacked to death in their home in Fall River, Massachusetts. Accused of killing her father and hated stepmother, their 32-year-old daughter, Lizzie, became the subject of exhaustive media coverage.

A century before O.J. Simpson hired what the media called a legal “dream team,” Borden had a star-studded defense team that included a former governor and the Borden family lawyer. Like the Simpson case, the legal strategies of the prosecutor and the Borden defense team were subjected to much media scrutiny.

Most of the evidence against Borden was circumstantial; in the end, she was acquitted by an all-male jury that may have found it difficult to believe a respectable spinster could commit such a horrific crime.

Yet, Borden was never able to escape the stigma of having been accused of murder. Upon being set free, she found herself ostracized by former friends. For years, newspaper coverage documented Borden’s life after her acquittal. Since her death, the countless books, articles, a made-for-TV movie – even a recent TV series about Borden’s life after the trial – demonstrate the staying power of the high-profile, 19th-century trial.

Like Borden, Simpson was able to use his class and wealth to his advantage. But he also was excoriated during and after his trial.

Celebrity crimes make good TV

Of course, there was no television in Borden’s time.

On Oct. 3, 1995, an estimated 150 million Americans tuned in to hear the jury’s verdict in the O.J. Simpson trial. It marked the culmination of 16 months of wall-to-wall, prime-time television coverage.

On the evening of June 12, 1994, Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend, Ronald Lyle Goldman, were slashed to death outside Nicole Simpson’s upscale condo in Los Angeles, California. After the police pursued O.J. Simpson’s white Bronco in a low-speed car chase that mesmerized TV viewers, O.J. Simpson was arrested and charged with the murders.

For the broadcast networks and their fledgling cable news counterparts, it was a recipe for high drama – and high ratings.

With a captivated nation glued to their TVs, radios and newspapers, media outlets rolled out a slate of trial experts to offer daily commentary. This template would become the norm for future celebrity trials, as a cottage industry of legal pundits would appear on the airwaves to comment on cases ranging from Tom Brady’s “Deflategate” lawsuit to the indictments of former President Donald Trump since he left office in 2021.

Post-trial research has found that audience perceptions of guilt or innocence in the Simpson trial were shaped by the amount – and type – of media consumed. The more someone became sucked into the daily happenings of the trial, the more likely they were to become emotionally invested in O.J.’s life. Developing what’s known as a parasocial bond, they became more likely to believe in his innocence.

How the media colors crime and race

When the jury declared Simpson innocent, reactions largely fell along racial lines. Throngs of white Americans responded with shock, dismay – even anger – while crowds of Black Americans responded with elation.

Polls and surveys later found people’s reactions to the verdict reflected not only their opinion about Simpson’s guilt or innocence, but also their beliefs about race and the fairness of the country’s criminal justice system.

Barbara Alper/Getty Images

Scholars today also realize that the media, when constructing narratives about crime and justice, will often fall back on tropes and stereotypes.

Shaped and reinforced by the media, these constructs influence how offenders and victims are perceived. For example, one 2004 study revealed that newspaper coverage tends to depersonalize female victims of violent crimes. And a 2018 study found that the race of a mass shooter will color how the media covers the crime and the accused, with the violent acts of white criminals depicted as unfortunate anomalies of circumstance and mental illness.

Simpson’s own relationship to race was always complicated.

In a 1970 New York Times article titled “For the Black Athlete, New Advances,” reporter Robert Lipsyte quoted Simpson describing how he had overheard a racial slur while attending a wedding with mostly white guests. Lipsyte wrote that race relations would have to improve dramatically for Simpson “to be able to transcend blackness in his public image.”

By the 1990s, Simpson seemed to have done just that. A middle-aged O.J. had achieved celebrity status, and he appeared to have transcended this blackness by distancing himself from poor and working-class black people, while gaining the acceptance of white people who saw him as a celebrity immune to the trappings of racial stereotypes.

Despite some incidents of domestic violence, Simpson had been able to maintain this genial reputation – until he was accused of the murder of his white ex-wife and her friend.

Simpson’s fall from grace was symbolized by a controversial 1994 Time magazine cover photo, which some claim was altered to make Simpson’s skin appear darker.

By 2014, the gap between how Black people and white people viewed Simpson’s verdict had narrowed: Black people were far more likely to believe that Simpson was guilty.

However, Simpson’s fragile public image was a reminder of the limits of his ability to transcend race. And there’s no indication that Black Americans have any more confidence in the U.S. criminal justice system today than they did in 1995.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Feb. 3, 2016.![]()

Frankie Bailey, Professor of Criminal Justice, University at Albany, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.