Review by Doug Gibson

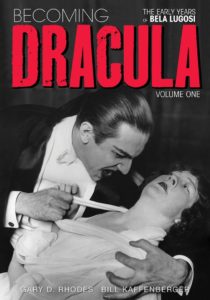

“Becoming Dracula: The Early Years of Bela Lugosi: Volume 1,” (BearManor Media, 2021) is an absolutely superb targeted biography of Lugosi’s first 38 years, from the son of a baker-turned-banker in Lugos, Hungary (now part of Romania) to late 1920, when the already acclaimed Budapest/Berlin thespian arrived penniless in New Orleans, La.

Authors Gary Rhodes and Bill Kaffenberger have collaborated before on Lugosi books. They pored over well-over-century-old documents to unearth many new facts on Lugosi’s early life and career, and they clarified and corrected information — not completely accurate — due to fanciful press interviews. Also corrected is some long-used incorrect information, including where Lugosi performed as Jesus Christ. He did not debut in The Passion in Debrecen, Hungary, but in Budapest in 1912.

Readers accustomed to thinking of the former Bela Blasko as only a creature of the night will enjoy the authors’ account of Bela’s steady rise through the Hungarian acting community. He started very small, gained stature in the provinces, playing a wide variety of roles. He did not get the call the first time he auditioned to perform in Budapest. But he gained great provincial acclaim as a talented, very handsome actor in cities such as Debrecen, and Szeged. After 1912, he became a frequent Budapest actor, with a very large fan base.

He performed in so many play adaptations. Here’s just a few: Trilby, Romeo and Juliet, Anna Karenina, The Tragedy of Man, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Taming of the Shrew, Richard III, and, of course The Passion. He even eventually played — in a film — a “vampire,” but it was not the undead type. It was the mortal, devious seducer type.

As the authors note, he did not always play the lead, or even a supporting role. Hungary’s thespian community was one where actors played multiple types of roles, even extras. The authors hypothesize that some of Bela’s roles may have been as obscure as a face in a crowd. But he did play many major roles, and the scores of newspaper articles gathered by the authors underscore his popularity and notoriety. He was at times criticized for overacting, or over-emoting.

The authors describe a pre-World War I Budapest that must have been thrilling for those within and interested in the arts and politics. The cafes of the city were places for passionate discussions of the arts and politics. Reading Rhodes and Kaffenberger makes me yearn to go back in time just to traverse the Budapest of that era, enter a cafe, and listen to a verbose and very opinionated Lugosi hold court on the arts and politics.

World War I stymied the arts for a while, and also tempered the fervor of many Hungarians who fought for Germany, including the officer Lugosi, who was wounded. According to the authors, he convinced doctors he was mentally unstable, and needed a discharge. Lugosi may have suffered from what we now know as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He did have lasting physical wounds. As the authors note, he had a lifelong empathy with veterans of war.

Lugosi resumed acting on the stage, and also moved to film acting, initially under the name Arisztid Olt. The authors merit respect for tracking down reviews and plots of many Lugosi Hungarian films. Only a fragment of one film exists today.

Lugosi, long a matinee idol, also married for the first time, to Ilona Szmik, the daughter of a bank attorney.

Lugosi became politically radicalized after the war. He supported communist government leaders. He was a communist. When one leader was pushed out by a more extreme communist government led by Bela Kun — who was a puppet of Russia’s Lenin — Lugosi unwisely embraced Kun. He became a labor leader for the new government, in an era of increasing political violence.

While Lugosi appears to have eschewed violence, the inevitable overthrow of Kun by a rightest alternative, and inevitable reprisals, placed Lugosi in real danger. He and his wife fled to Vienna. Soon afterwards, Ilona’s parents, opposed to Lugosi’s politics, persuaded their daughter to leave Vienna, return to Budapest and divorce him. In what seems unfair, the divorce was granted on claims that Bela had deserted Ilona

Bela could not chance a return to Budapest. Based on a mistaken-identity warrant, he was charged with serious crimes. The actual perpetrator had a similar name and was also an actor. The warrant was not withdrawn until the mid 1920s, with Lugosi already in the United States.

Lugosi relocated to Berlin, and re-invigorated his career. As the authors note, post-World War I Berlin was a “Babylon” of sorts, with a culture of promiscuity (Lugosi enjoyed his share of that) and a more permissive attitude among the arts. Although not always the star, Lugosi was very active, appearing in more than a dozen German films. One, heavily edited for U.S. release from 1920, survives under the title “Daughter of the Night.” It can be viewed on YouTube and other streaming services.

Why Lugosi abruptly left for the United States, without much funds, is open to debate. Perhaps he was still worried about being arrested? The authors suggest maybe a love affair went bad. More likely, they opine, is Lugosi was depressed after Ilona filed for divorce in June of 2020.

I look forward to Part 2 of the book, slated for summer release. It’s another must-have book from Rhodes and Kaffenberger. Due to the very large amount of new information unearthed through old-fashioned, shoe-leather reporting and research, I list it, along with “Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain: Second Edition,” by Frank Dello Stritto and Andi Brooks, as the two best targeted biographical works on Lugosi. (This review is cross-posted at The Plan9Crunch blog).