President Joe Biden’s hardline policies towards China may be good for domestic electoral politics but are likely to trap him in positions that he may not be able to undo without looking weak to countries in central, south and south-east Asia.

Biden is resurrecting decades-old post-Cold War doctrines about spreading democracy and human rights as central tenets of his foreign policies. He sees them as steppingstones to restoring US leadership over world affairs after the disruptions caused by former president Donald Trump.

This may be unsuited to the current realities of a rapidly advancing digital global village where Asian countries offer the fastest growing markets.

The Biden administration’s first high-level meeting with China takes place today in Anchorage, when Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan meet China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi and its most senior foreign policy official, Yang Jiechi.

The Chinese have been conciliatory in comments during the build-up but Blinken was blunt, describing China as “the only country with the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to seriously challenge the stable and open international system.”

Blinken has rightly called the US-China relationship “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century.” The problem is that both sides want to meet each other from positions of strength although neither has enough strength to strong arm the other.

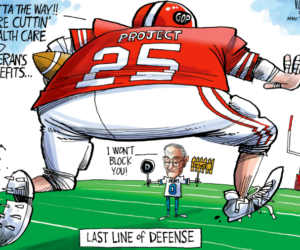

Biden may have to soft-pedal his castigation of democracy and human rights in China if he wants Beijing’s cooperation on climate change, North Korea, nuclear proliferation, Afghanistan, Iran, the Middle East and other matters of common interest.

These are also prime concerns for central, south and south east Asian countries, which will struggle for a long time with the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermaths. They may give wider berth to Biden’s Washington to avoid being caught in the middle of US-China disputes arising more from domestic politics than sensible foreign, trade and security policy needs.

There is growing suspicion that in Cold War-style, Biden is preparing to use democracy promotion and human rights as weapons of foreign policy to impose sanctions against rivals and preserve US leadership.

Like Beijing, most of the region’s countries do not care much for American interpretations of democracy and human rights. They have also begun to doubt the fairness of US democracy and the many ways in which political parties manipulate electoral politics to stay in power.

The US-China relationship is a complex guerrilla conflict between two prickly powers that have not a modicum of trust in each other. Washington would do well to be as clear-eyed about its own limitations as it is of Beijing’s authoritarianism and other flaws.

The starting point for many US experts is that China sees the US as a declining power and wants to do all it can to accelerate that downfall. But that portrays Xi as a naïve leader steeped in jealousy of American power.

Xi’s obsession is not with US power but with demonstrating to all his 1.4 billion people that the Communist Party of China deserves respect and obedience. He wants them to believe it is their sole protector and source of prosperity and technological progress.

The Communist Party celebrates its 100 year birthday this summer and Xi does not want to get involved in arguments with Biden’s White House that might mar his image as the avuncular strongman leader of his people.

There is bipartisan loathing in the US for China’s dictatorial communist regime, its human rights atrocities against the Uyghur minority, destruction of democracy in Hongkong, and state-dominated economy and social life.

But the reality is that China is an economic and technology juggernaut. Washington does not have the power to intimidate it regardless of European allies, Japan, South Korea, Japan, Australia, India and other friends in Asia.

Trump used many economic weapons from America’s stockpile, including draconian tariffs and sanctions against China’s best high-tech firms like Huawei to intimidate Beijing. But he failed to make Chinese President Xi Jinping budge significantly.

Now Biden’s aggressive words are bark without bite. They are unlikely to produce better results against a Communist leadership that did not flinch under Trump’s rain of sticks and bricks.

The US is the planet’s mightiest military power but using it against Beijing is not an option because launching missiles against mainland China may bring nuclear retaliation against the US homeland.

It may be foolhardy to use US forces or aircraft carriers in the region to destroy targets in mainland China to protect Taiwan or the interests of Japan, South Korea and the Philippines.

Washington may also be alone in such a situation because Europe’s NATO allies may hesitate to stand with US forces since they do not have similar defense commitments in the region.

Fighting China for any reason will not be like destroying Saddam Hussein’s military in Iraq, the Taliban in Afghanistan, or Muammar Gaddafi’s military in Libya. Those were possible because the US military had freedom of the skies and their militaries were decrepit.

China will not surrender freedom of its skies and its military has weapons capable of competing with America’s arsenal at every level. So, Biden, Blinken and Sullivan have no alternative to engaging in negotiations with China on every issue that concerns them.

For that reason they should be wary of humiliating China with words unless they have the actual power to make it change behavior. Otherwise, Biden will lose respect in Asian cultures.

Photo 185928759 © Frédéric Legrand – Dreamstime.com