History, one might presume, is an assemblage of facts, and the longer and more complex a particular history is the more facts there are. But facts are malleable, and it took me many years of history reading to come to understand that they too often are merely reflections of historians’ perspectives — the political axes they happen to grind. This may be no truer than in the modern history of the Middle East because of the diet of chauvinistic Eurocentric claptrap that we have been force fed beginning with school texts and continuing through the tsunami of books extolling the benevolent greatness of the once and future colonial powers.

That Scott Anderson refuses to buy into this big lie is chief among the many virtues of his magnificent new geopolitical history, Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East. While nominally a biography of the heroic if quixotic T.E. Lawrence, played to such great effect by Peter O’Toole in David Lean’s 1962 cinematic masterpiece, it more importantly is the tale of British duplicity, with ample help from the French and the quasi-involvement of feckless Americans, in double-crossing the Arabs in the wake of their successful revolt against their Turkish oppressors in the closing days of World War I.

Having been promised self-determination in the form of their own homeland as a reward for crushing the Ottoman Empire in its inhospitably arid western expanses, the Arabs instead were left with sloppy seconds as the imperial powers arbitrarily carved up the region, ostensibly at the post-war Versailles Peace Conference but in reality as a result of the Sykes-Picot Agreement hammered out in secret two and a half years before the Armistice.

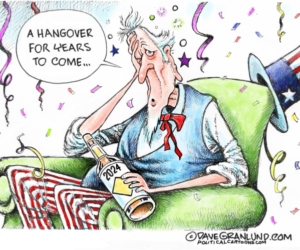

The upshot was the artificial boundaries of colonial Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, and eventually the state of Israel, as well. The predictable result — and it broke Lawrence’s heart as the Arabs’ only true champion — has been never ending ethnic strife, poverty, disenfranchisement, religious extremism and, of course, terrorism. Long story short, the Iraq, Iran and now Syrian crises were not accidents, but inevitabilities.

“Ever since [the end of World War I], Arab society has tended to define itself less by what it aspires to become than by what it is opposed to: colonialism, Zionism, Western imperialism in its many forms,” Anderson writes. As a New York Times op-ed columnist recently noted, this culture of opposition has enabled generations of dictators to distract attention from their own misrule.

And in one of his most prescient comments, Lawrence discarded the fiction relentlessly peddled by the Great Powers that the Arabs would accept a Jewish nation in their midst. Instead, he predicted that “if a Jewish state is to be created in Palestine, it will have to be done by force of arms and maintained by force of arms amid an overwhelmingly hostile population.”

Oh, and let us not forget that the emergence of the U.S.’s best regional buddy, Saudi Arabia, and its terrorist-breeding, ultra-conservative Wahhabist form of Islam, is a result of the stew concocted by Britain and France.

Things might not have worked out a whole lot differently had those nations kept their promises. But we will never know because once planted, the toxic seed of imperialist duplicity has not and never will be completely eradicated. While the Arab Spring is a beautiful thing, the tortured history that preceded it and its uncertain future are an inevitable result of the folly alluded to in the subtitle of Lawrence in Arabia.

Lawrence is, of course, the primary focus of Lawrence in Arabia, but Anderson artfully weaves in the stories of four other key but comparatively little known characters: Curt Prufer, a German scholar turned spy and Turkish adviser; Djemal Pasha, a Turkish leader who showed equal parts compassion and ruthlessness; William Yale, a New England blue blood and State Department special agent while on Standard Oil of New York’s payroll, and Aaron Aaronsohn, an agronomist and master spy who was at odds with most other advocates of a Jewish state and contemptuous of the dirt poor Palestinians who would be displaced.

While Lawrence helped the Arabs win the war but could not help them win the peace, his lasting legacy is his plea that Westerners discard their stilted thinking about Arabs and immerse themselves in the local environment, wherever it might be, as to know “its families, clans and tribes, friends and enemies, wells, hills and roads.”

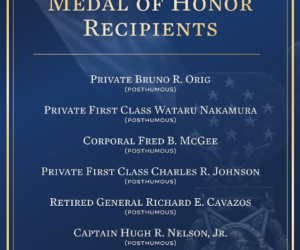

Lawrence is best known for Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a sometimes overly fanciful yet fascinating account of his years as a liaison officer with rebel forces during the Arab Revolt on which the Lean movie is based. But it is his Twenty-Seven Articles, a treatise written for his superiors in 1917, that continues to have profound influence today. Nearly a century later, Twenty-Seven Articles has the force of revelation, and amid the American military “surge” in Iraq in 2006, General David Petraeus ordered his senior officers to read it so that they might better learn how to win the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people.

Today’s State Department diplomats — whether toiling in Benghazi or Beirut — would be well advised to do the same.

Two other books that I’ve recently read brilliantly capture the transcendental futility of World War I: Robert Graves’ autobiographical Good-Bye to All That and Mark Helprin’s fictional A Soldier of the Great War.

Good-Bye (1929), which is considered to be one of the greatest of non-fiction books, traces Graves’ monumental loss of innocence as a captain in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers as he grapples with the horror of the war and later bitterly bids farewell to England and its absurd class culture. A Soldier (2005) is the magnificently told story of a prosperous Roman lawyer whose life is shattered by the war. He becomes a hero, then a prisoner and deserter who wanders through a ravaged Europe, in the process losing one family for another.