Warner Bros.

Meisha Lohmann, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Several years ago, I made a visit to a local book sale and came across a rare 1964 edition of Roald Dahl’s “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” Popular in its own right, the novel has also served as the inspiration for a number of movies, including “Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory” – the classic 1971 movie starring the late Gene Wilder – a 2005 reboot starring Johnny Depp, and “Wonka,” the 2023 version.

As a child of the 1980s, I had voraciously consumed Dahl’s novels, so I knew the book well. But the illustrations in this particular edition looked unfamiliar.

Once I brought the worn and tattered book home and began to read it aloud to my kids, I realized that some passages looked unfamiliar as well. My voice faltered as the Oompa-Loompas – the pint-sized workers in Wonka’s chocolate factory – appeared and Charlie asked, “Are they really made out of chocolate, Mr. Wonka?”

To which Wonka replied: “Nonsense!”

“They belong to a tribe of tiny miniature pygmies known as Oompa-Loompas,” Wonka explains in this version of the book. “I discovered them myself. I brought them over from Africa myself – the whole tribe of them, three thousand in all. I found them in the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had ever been before.”

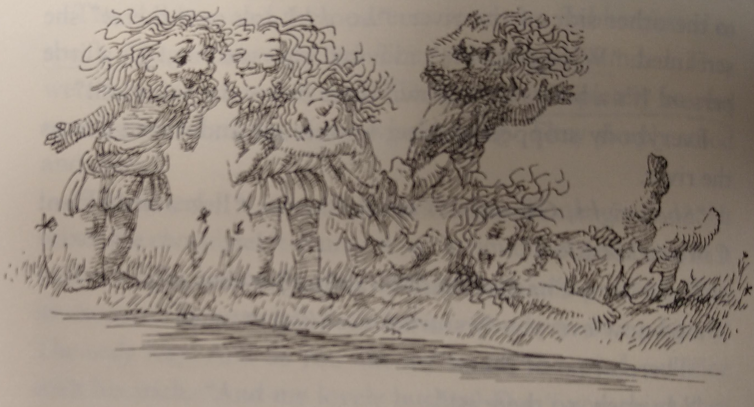

The accompanying black-and-white illustration of several dark-skinned Oompa-Loompas left me stunned.

Dahl’s book is part of a long history of children’s books that feature racist stereotypes – a list that includes six Dr. Seuss books that were removed from publication in 2021. Other children’s classics, such as “Peter Pan” and “Mary Poppins,” have also been criticized for perpetuating racism.

As an English lecturer who specializes in decoding some of the hidden meanings and dark realities in popular children’s stories, I looked deeper into the blatant racism in the 1964 edition of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” comparing it to a more recent copy from 2011.

Notably, the description of the Oompa-Loompa’s skin had been changed from “almost black” to “rosy-white.” And rather than coming from Africa, they came from “Loompaland.” I learned that these changes were made by Dahl for the 1974 edition after criticism by the NAACP and others. Dahl’s response was to remove the Black characters altogether.

Yet as philosophy lecturer Ron Novy points out, even the latest editions of the book still perpetuate racist and imperialist ideologies.

Parallels with slavery

When Wonka describes how he “smuggled” the Oompa-Loompas into the country in “large packing cases with holes in them,” the image clearly recalls slave ships navigating the Middle Passage. Wonka’s promise to pay the Oompa-Loompas’ wages in cacao beans, and the admission that no one ever sees them come in or out of the factory, reinforces the Oompa-Loompas’ subjugation to Willy Wonka, who plays the role of their “Great White Father,” as fourth grade reading teacher Katherine Baxter noted in 1974.

Historian Donald Yacovone has pointed out that, even in its revised form, “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” has long contributed to the perpetuation of white supremacist ideology. Not only do the Oompa-Loompas immediately appear – ready to obey – whenever Wonka clicks his fingers, but Wonka is also repeatedly dismissive of them. He calls them “charming” but tells his visitors not to believe a word the Oompa-Loompas say. “It’s all nonsense, every bit of it!”

Wonka even uses the Oompa-Loompas as experimental subjects. He feeds them gum that turns them into blueberries and fizzy drinks that send one unfortunate man aloft until he “disappeared out of sight” and was never seen again. These experiments seem a grotesque parody of the myriad cases of enslaved and free Black Americans who have been subjected to experimental surgeries, treatments and medical neglect.

In both the book’s current version and in the original, he smuggles them into his factory and pays them in cacao beans because they were “practically starving to death” and cacao was “the one food that they longed for more than any other … but they couldn’t get it” on their own.

It’s an absurd assertion that this community of people, originally located in the heart of Africa, cannot access a crop that, while native to the Amazon, is primarily grown in West African countries. That they need Wonka to give them access to the resources of their own land is a damaging colonialist fantasy – one which, as Yacovone notes, has historically buoyed, rather than diminished, the popularity of the novel and the 1971 and 2005 films.

Maintaining the status quo

Unfortunately, the latest Wonka movie also engages in the type of implicit racism that remains in the revised 1974 version of the novel. The most prominent Black character, a girl named Noodle, played by the talented Calah Lane, takes a back seat to Wonka in the major events of the film.

The new Wonka almost broke from the tradition of having Wonka played by white men. Early in the new film’s conception, Newsweek reported that actor, comedian and musician Donald Glover was under consideration for the lead role, a choice that could have at least begun to force a rewrite of the original novel’s racist narrative.

Instead, the film casts Noodle in the position of an unfortunate Black girl who can only hope for a ride on Wonka’s velvet coattails.

“I know things haven’t been easy for you,” Wonka says in the movie. “They’re going to get better.”

“You promise?” Noodle replies, hopefully, and he does promise, highlighting his role as her white savior. Another character in voice-over agrees: “You could change her life, Mr. Wonka. Change all their lives.”

I was initially hopeful about the prospect of a movie that moves away from the novel’s racist origins, yet still imparts the power of imagination on a new generation. Unfortunately, moviegoers may find themselves having to hold their breath and make a wish, as Gene Wilder stated in a song from the 1971 movie, for a version that holds no remnants of its racist past.![]()

Meisha Lohmann, Lecturer in English Literature, Binghamton University, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.