AP/Chick Harrity

Ken Hughes, University of Virginia

Like Donald Trump, Richard Nixon tried to stonewall congressional investigations into crimes allegedly committed in the White House.

“Why, we’ll just let it go to the (Supreme) Court. Fight it like hell,” Nixon said.

But the stone wall crumbled under pressure from the public, Congress and the courts, and its rubble formed the foundation for an article of impeachment.

As the Senate Watergate investigation began in 1973, Nixon took a position like Trump did on May 2, when he barred former White House counsel Don McGahn from testifying before Congress about potential obstruction of justice by the president.

To block current and former White House aides from testifying before Congress, Nixon claimed that “executive privilege” shielded presidential conversations from congressional oversight.

And just as Trump claimed on Wednesday that executive privilege allows him to withhold the complete, unredacted Mueller report from Congress, Nixon claimed it allowed him to withhold executive branch documents.

AP/Alex Brandon

Why Nixon resisted

Nixon’s claims of executive privilege were a matter of political survival.

One of the crimes for which Congress was investigating Nixon was obstruction of justice, and he was guilty.

There is no credible evidence that Nixon knew about the underlying crime, the Watergate break-in, until after the burglars got caught.

But Nixon did know that some of those involved in the break-in were linked to other crimes he personally initiated, such as the illegal leaking of information obtained from grand juries to discredit his political enemies.

The president had obstructed the FBI investigation of Watergate to conceal his own crimes. On June 23, 1972, for example, in a conversation captured on his own secret White House taping system, Nixon approved a plan to use the CIA to obstruct the FBI investigation. This tape ultimately became known as “the smoking gun,” since it proved that Nixon was guilty of obstruction.

Nixon was using “executive privilege” to conceal his obstruction from Congress and the Watergate special prosecutor.

Political survival

Nixon could not hold the hard line for long. It made him look guilty, even to supporters, who started asking why he didn’t just let his aides testify if he was innocent.

And when former aides decided to testify against him, as former White House counsel John W. Dean III did on national television, it was obvious Nixon had no power to stop them.

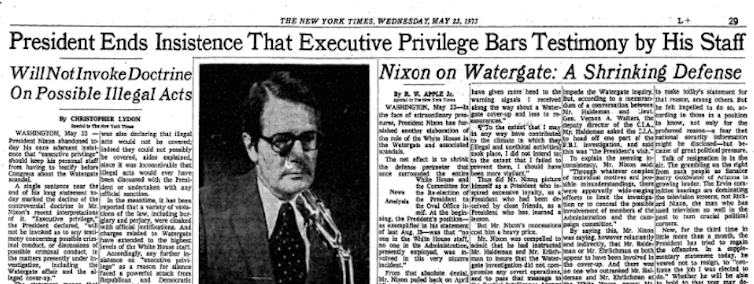

Screenshot, NY Times archive

If Nixon wanted any current or former White House aides to testify in his favor – there were many who were willing to, from H.R. Haldeman to Patrick Buchanan – and offset the bad publicity he was getting from the hearings, he had to reverse himself. In May 1973, Nixon announced that “executive privilege will not be invoked as to any testimony concerning possible criminal conduct.”

But he still withheld White House documents.

Again, it was a matter of political survival. He could plausibly deny testimony against him, but it was impossible to deny his own voice on tape.

Struggle over privilege

Once the existence of his secret tapes was revealed to Congress in July 1973, they became the center of the struggle over executive privilege.

Congress and the special prosecutor wanted the tapes, because they could prove once and for all who was telling the truth. Nixon withheld them for that same reason.

The issue came to a head once the House Judiciary Committee began an impeachment inquiry.

The committee’s ranking Republican, Rep. Edward Hutchinson of Michigan, said at the inquiry’s outset that he “would tell (the White House) that executive privilege in the face of an impeachment inquiry must fall.”

The notion that the president enjoys the privilege of withholding information from Congress is based in the constitutional separation of powers, but impeachment is an exception to that separation. Impeachment is a legislative check on executive power, just as the veto, for example, is an executive check on legislative power.

Nixon’s own Justice Department could not find a single example in history of anyone ever invoking executive privilege in an impeachment inquiry – not even Andrew Johnson, the only president to have been impeached by that point. (Congress can impeach any civil officer of the U.S. government.)

When the Judiciary Committee subpoenaed Nixon’s tapes, Nixon refused to turn them over, saying he had already provided Congress with “the full story of Watergate.”

National Archives via the AP

The court acts, the president resigns

But Nixon was forced to give his tapes to the special prosecutor when the Supreme Court decided 8-0 on July 24, 1974, that executive privilege did not give a president the right to refuse to hand over evidence in a criminal trial.

Within a week, the Judiciary Committee voted 21-7 to impeach Nixon for defying congressional subpoenas.

“If we do not pass this article today, the whole impeachment power becomes meaningless,” said Rep. Lawrence J. Hogan, a Republican of Maryland, father of the current Maryland governor, Larry Hogan.

In August, publication of a transcript of the the smoking gun tape confirmed that the president was guilty of obstruction of justice. Nixon resigned rather than give Congress the chance to remove him.

His claims of executive privilege had helped him hold onto power an extra year. Invoking executive privilege was not a winning play – but it was the last one available to a guilty president.![]()

Ken Hughes, Research Specialist, the Miller Center, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.