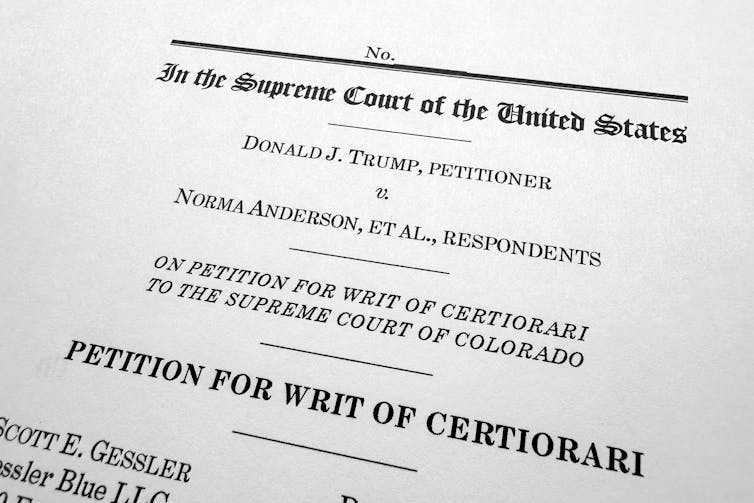

Stefani Reynolds/Getty Images

Derek T. Muller, University of Notre Dame

Momentous questions for the U.S. Supreme Court and momentous consequences for the country are likely now that the court has announced it will decide whether former president and current presidential candidate Donald Trump is eligible to appear on the Colorado ballot.

The court’s decision to consider the issue comes in the wake of Colorado’s highest court ruling that Trump had engaged in insurrection and therefore was barred from appearing on the state’s GOP primary ballot by Section 3 of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Maine’s secretary of state also barred Trump from the state’s primary ballot, and more than a dozen other states are considering similar moves.

The Conversation’s senior politics and democracy editor, Naomi Schalit, spoke with Notre Dame election law scholar Derek Muller about the Supreme Court’s decision to take the case, which will rest on the court’s interpretation of a post Civil War-era amendment aimed at keeping those who “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” from serving in political office.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

On a scale of 1 to 10, how big is this?

In terms of potential impact, it’s a 10. It is excluding a former president from appearing on the ballot for engaging in insurrection.

That’s monumental for several reasons. It’s the first major and material use of this provision of the Constitution since the Civil War. It’s the first time it has kept a presidential candidate off the ballot, much less a former one and the apparent front-runner for the Republican Party nomination.

But on the flip side, what are the odds of that actually happening? That’s more speculative. And so the number is probably less than 10. This was an extraordinary major decision from the Colorado Supreme Court. But you have to temper that by saying, well, there’s a chance it gets reversed, and then Trump appears on the ballot and this mostly goes away.

What are the risks here for the court? Legal scholar Michael W. McConnell at Stanford said in The Washington Post, “There is no way they can decide the case without having about half the country think they are being partisan hacks.”

This is a binary choice that either empowers the Republican candidate or prevents voters from choosing him. So when you have a choice in such stark, political and partisan terms, whatever the Supreme Court is doing is often going to be viewed through that lens by many voters.

I think it’s a reason why there will be as much effort as possible internally on the court to reach a consensus view to avoid that appearance of partisanship on the court, that appearance of division on the court. If there’s consensus, it’s harder for the public to sort of point the finger at one side or another.

That’s much easier said than done. The court decides questions with major political consequences all the time. But to decide the questions in the context of an upcoming election feels different.

The justices granted only Trump’s appeal to consider the case, not the Colorado Republican Party’s. Is this significant, and if so, how?

The Colorado Republican Party and the Trump campaign were on two different tracks in their appeals. When you grant both cases, you invite two sets of attorneys and parties to participate and add complexity. I think the decision to grant only Trump’s case is a decision to make this as streamlined a process as possible.

Will whatever decision the court makes put to rest the ballot access questions in all the other states?

There are a couple of very narrow grounds the court might rule on. For example, they might say, we’re not ready to hear this case because it’s only a primary, or Colorado so abused its own state procedures as to run afoul of federal constitutional rules. Those would be kind of rulings only applicable to the Colorado case or only applicable in the primaries.

There’s a chance the court does this, but my sense – not to speculate too much – is that’s going to be deeply unsatisfying for the court, knowing that if they delay in this case, another case is likely coming later in the summer where these questions will have to be addressed in August or September. That’s much closer to the general election. Those are months when the court is in recess, and they would have to come back from their summer vacation early. So my sense is that the court will try to resolve these on a comprehensive basis. They’ve scheduled oral argument on Feb. 8, 2024 so they want to move on as quickly as possible to put this to rest.

AP Photo/Jon Elswick

You submitted an amicus brief in the Colorado case for neither side. What was it you wanted to tell the court?

I raised two general points and then one specific to Colorado. The two general points are that I think states have the power to judge the qualifications of presidential candidates and keep them off the ballot. And states have done that over the years to say if you were born in Nicaragua, or you’re 27 years old, we’re going to keep you off the ballot.

But I also say states have no obligation to do that. You can look throughout history, going back to the 1890s, where ineligible candidates’ names have been printed and put on the ballot. And this isn’t a question of whether or not the state wants to do it – they have the flexibility to do it. So I wanted to set those two framing questions up so the court doesn’t veer too much in one direction or the other to say “states have no power,” or “of course states have power regardless of what the legislature has asked them to do.”

The point specific to Colorado is I doubted there was jurisdiction in Colorado for the state Supreme Court to hear this case, but the court disagreed with me.

What could happen during the period between now and the court’s decision that could be consequential?

More states are going to consider these challenges as the ballot deadlines approach. And we know that there’s Super Tuesday the first Tuesday of March when a significant number of states hold presidential primaries. So I think there’s a lot of uncertainty in the next six weeks about which states might exclude him.

On top of that is voter uncertainty. Voters are making their decisions and weighing the trade-offs of who to vote for. Right now, this is a cloud hanging over the Trump campaign. It’s not just that he’s been declared ineligible in Colorado and Maine. It’s the question in other states for other voters: Am I wasting my vote, is this actually an ineligible candidate? Should I be voting for somebody else?

That’s not an enviable position for voters to be in – that they might cast their ballots only to find out later that they’re not going to be counted.![]()

Derek T. Muller, Professor of Law, University of Notre Dame

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.