AKA “tracing the provenance of a photograph”

On 19 February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which led the Pentagon to “[define] the entire West Coast … as a military area.” The result: internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans; two-thirds were citizens.

In one of our most shameful acts as a country, we forced Japanese Americans to abandon their homes and businesses. We shipped them off to military internment camps scattered around the country.

In 1944, in Korematsu v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the government, upholding the constitutionality of the executive order and internment in a 6-3 decision. Yet our government was not playing fair:

In 1983, a pro bono legal team with new evidence re-opened the 40-year-old case in a federal district court on the basis of government misconduct. They showed that the government’s legal team had intentionally suppressed or destroyed evidence from government intelligence agencies reporting that Japanese Americans posed no military threat to the U.S. The official reports, including those from the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, were not presented in court. On November 10, 1983, a federal judge overturned Korematsu’s conviction in the same San Francisco courthouse where he had been convicted as a young man (emphasis added).

The 1944 Supreme Court decision still stands.

We would not apologize until 1988, when President Ronald Reagan “signed a bill to recompense each surviving internee with a tax-free check for $20,000 [a pittance] and an apology from the U.S. government.”

But here’s the rub: the 1942 action did not come out of the blue. In the 1920s, white residents in Hollywood were agitating against Japanese American ownership of land.

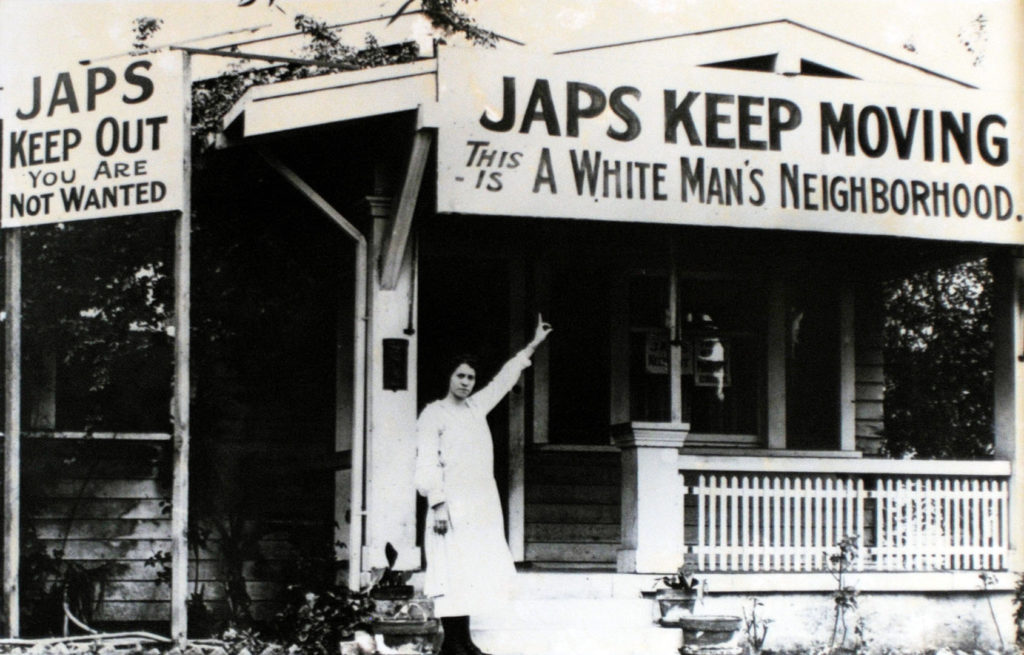

“Japs keep moving”

When I started looking for an image to illustrate this post, the one that I’ve chosen popped up, but without any provenance. (This copy is from the National Park Planner, which credits no one: “Anti-Japanese immigrant photo.”)

One Flickr share credits an Ellis Island exhibit but provides no other context (such as location or date). Another credits the Minidoka Internment National Monument display inside the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument visitors center (also no additional context). Here’s one from Manzanar prison camp, which helps explain why some think the photo is from the 1940s. A fourth implies that the photographer might be Rebecca Dramen (but no Google search validated that idea).

A Smithsonian reference dates a cropped version of the photo to 1920 (it is from 1923) and credits the National Japanese American Historical Society. This link is in a StackExchange post.

The Smithsonian has a very large collection of photos related to Japanese Americans and the Constitution which is accessible by search. The photo collection is part of what appears to be an older online exhibit which is Flash-based; that helps explain why it doesn’t show up well in a Google search.

There’s an orphan page with no details at OSU; a colorized post card; and a blogspot post from 2012, with the following comment:

The lady in that picture was my grandmother Mimi – my grandfather was very racist – she wasn’t. She was a descendant of the Spanish Land Grant families. The house on Tamarind Ave. is no longer in the family – it was very embarrassing to the family when that picture was published in the April ’86 issue of National Geographic, maybe to make up for bad karma my daughter and a cousin love Japanese culture.

The Hollywood Protective Association

I learned that west coast bigotry was much older than the WWII internments while tracing the origins of this photograph. In the 1920s, white people formed the Hollywood Protective Association, with the goal of keeping Hollywood “white.”

In April 1923, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce told white residents, who were upset because Japanese Americans had purchased eight parcels of land, to “[urge] residents to agree to restrict the use of land to those of the Caucasian race.”

The angry white people had formed a group called the Hollywood Protective Association and started circulating petitions “asking residents not to sell their land to Japanese.” By June some bunch of geniuses called the Los Angeles County Anti-Asiatic Association had invited the mobbed-up Hollywoodies to join their umbrella gang, assuring them that they were “prepared to back them in every possible way to keep their districts white.”

If you, like me, have not heard of this group, perhaps it is because we aren’t from the LA area. Or are white. Or haven’t taken it upon ourselves to learn about the bigotry that peppers our history.

From The factors affecting the geographical aggregation and dispersion of the Japanese residences in the city of Los Angeles, Koyoshi Uono. University of Southern California, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1927, p. 140:

And lo and behold, there is my photo: immortalized in a dissertation from 1927. The photo ran in the Los Angeles Examiner on 18 May 1923.

Credit photos!

Finally, an ongoing plea to credit the source of any photo your share online, including those that you have taken yourself.

This is also a plea to honor copyright (search Creative Commons licensed photos first), but at a minimum link back to the source. If that source has no information on provenance, either do the work (and yes, it’s work) or DON’T LINK TO THAT IMAGE.

Learn more

- Japanese American National Museum

- Library of Congress, Newspaper collection, Japanese-American Internment

- National Archives, Japanese relocation during WWII

- PBS, Children of the camps

- Reuters, 75 years later, Japanese Americans recall pain of internment camps

- Smithsonian, The Injustice of Japanese-American Internment Camps Resonates Strongly to This Day

- The Atlantic, WWII: Internment of Japanese Americans

:: Cross-posted from WiredPen

:: @kegill

Known for gnawing at complex questions like a terrier with a bone. Digital evangelist, writer, teacher. Transplanted Southerner; teach newbies to ride motorcycles. @kegill (Twitter and Mastodon.social); wiredpen.com