The COVID-19 pandemic has had a serious impact on our military in terms of casualties among our troops and in posing a challenge to its ability to remain at top readiness and continue its core missions.

More than 5,000 service members have now tested positive for the virus and two have died.

The U.S. Navy has been especially hit hard, with coronavirus cases on more than two dozen Navy battleships. Most strikingly, the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt has been sidelined for more than a month, with the number of coronavirus cases now exceeding 1,000.

Fortunately, our nation is not engaged in any major military combat action nor is it facing any direct and imminent major military threat.

Such was not the case during World War I when the apocalyptic Spanish Influenza or “Spanish Flu” broke out.

The Spanish Flu, unrelated to Spain, broke out in the United States in March 1918 as the Great War was raging in Europe.

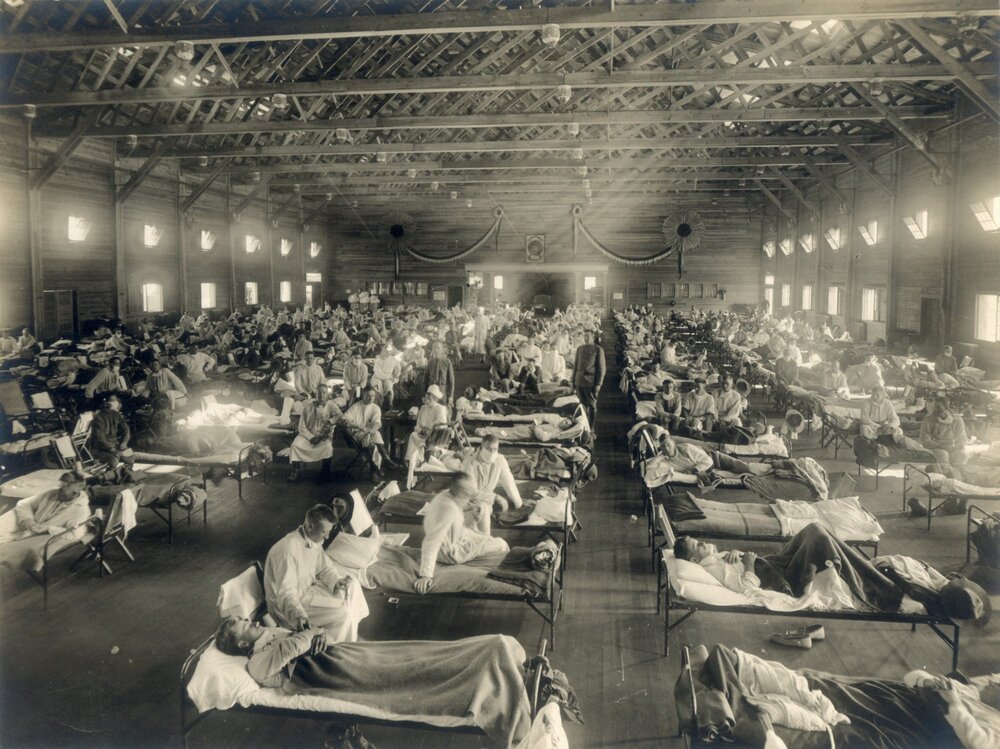

While scientists are still not sure where the virus first emerged, ironically and unfortunately, in the U.S., the flu was reportedly brought from nearby Haskell County, Kansas, to the sprawling Army training installation Camp Funston – home to 54,000 troops — in early March 1918. At the camp, the virus spread quickly. By the end of March, the virus had hospitalized more than 1,000 troops and killed 38.

From Camp Funston, the virus spread like wildfire to major military training camps in the U.S. and, from there, infected soldiers deploying to Europe carried the flu with them into the deadly trenches on the Western Front. There, the virus jumped across and behind enemy lines. The disease was also spreading fast into U.S. civilian communities.

In 1918, 340,000 U, S, soldiers were hospitalized for influenza, while 227,000 soldiers were in the hospital due to wounds suffered in battle.

Worse, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive alone, 1,451 Americans died from the flu and more soldiers were evacuated from the front with influenza than for wounds suffered in combat.

Then, as troops returned home, they brought back with them a far deadlier strain of the Spanish flu and infected thousands more in the general population. The second wave struck down especially those in the prime of their lives, those between the ages of 18 and 35.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, “over 25 per cent of the entire male population of the country between the ages of 18 and 31 were in military service” during that period.

The pandemic continued beyond the armistice into 1919 and finally faded in the early 1920s. But not before, in all its waves, forms and mutations, hospitalizing almost 800,000 American soldiers, killing approximately 45,000 of them (nearly 25,000 in Europe) and killing more than 600,000 Americans back home and an estimated 20 million to 50 million people around the world – other estimates run as high as 100 million. “An exact number is unlikely ever to be determined.”

The number of casualties the military has suffered thus far because of the coronavirus is, thank God, a far cry from the horrific toll the Spanish Flu took on our military.

But, are there lessons to be learnt from that painful chapter in our military history?

Here is one opinion:

In “Pandemics and the U.S. Military: Lessons from 1918,” Michael Shurkin, a senior political scientist at the non-profit, non-partisan RAND Corporation, takes note of the early (April 1) already mounting impact the coronavirus was having on the U.S. military, especially the outbreak on the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

After taking a close look at the difficult choices our country had to make during World War I and the devastating effect the Spanish Flu had on the military, Shurkin offers the following thoughts:

In early 1918, as the allies needed more manpower and the outcome of the war hung in the balance, the pandemic forced America’s military leadership to “prioritize mobilization [and accept] the human toll as a grim necessity.”

Fortunately, military leaders today face a more benign security environment than their predecessors a century ago, says Shurkin: “The U.S. military is engaged in military operations abroad, but it is not fighting a great-power war. As a result, the Pentagon has every reason to do everything in its power to stem the current pandemic — even if it has to absorb some downgrade in readiness.”

“America’s military leaders…have a number of advantages over their predecessors, including advances in medical technology, the sharing of information, and the fact that the United States is not currently involved in a major war…Moreover, modern warfare is relatively more compatible with strong public health measures than was the case back in the day,” Shurkin adds.

Shurkin:

[Therefore, it] stands to reason that military commanders — with some creativity and flexibility — should be able to protect the force during COVID-19 while minimizing negative effects on readiness. Downstream effects related to interrupted training, for example, may be inevitable. On the other hand, the price to be paid for not doing everything possible to impede the spread of the pandemic in terms of readiness and letting soldiers (along with their families and any other civilians with whom they interact) get sick could be significant.

Finally, Shurkin returns to the captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt rightfully prioritizing the health (and lives) of his ship’s crew while, on the other hand, President Woodrow Wilson and his Chief of Staff Gen. Peyton March “believed they had to throw every available man, sick or not, into battle in 1918.”

References:

PANDEMICS AND THE U.S. MILITARY: LESSONS FROM 1918

The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919