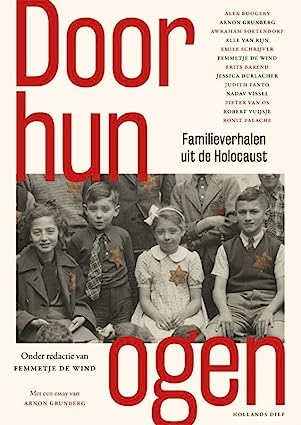

In one of her most recent books, Door Hun Ogen (Through Their Eyes) (below), well-known Dutch author Femmetje de Wind publishes a collection of heartrending interviews by young people of their Jewish grandparents, great-grandparents and other relatives who survived the Holocaust during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

One of the stories is by 10-year-old Joshua Pinto who writes how his great-grandfather, Sieg Parsser, and Parsser’s parents are grabbed by the Nazis in Amsterdam and eventually transported to the Bergen-Belsen death camp where his great-grandfather was murdered. As Allied troops approached, the Nazis — desperate to hide and destroy evidence of their abominable crimes against humanity — crammed Sieg and his mother, along with 2,500 other Jews, into a train headed away from the front enroute to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic.

The train, called der Verlorene Zug (the “Lost Train”), however zig-zagged aimlessly through eastern Germany for about two weeks before finally ending up near the small German village of Tröbitz, but not before its human cargo had suffered unspeakable misery, including malnutrition, disease and, for many (approximately 200) death due to starvation and various contagious diseases such as typhus and tuberculosis that spread like wildfire through the crammed cattle and freight carriages. Another 300 would die at the end of the ordeal. (The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum places the “exact number” of persons who died at 704.)

I remembered hearing about this “lost train” and did some research. There are numerous stories, reports, books, even a new movie, about the “Lost Train,” or the “Lost Transport,” or “the Train of the Lost.” While the names may differ and the accounts may vary as to certain details, dates and numbers, common threads emerge when it comes to the harrowing experiences endured by the Jewish prisoners.

There were in fact three trains that left an overcrowded, disease-ridden Bergen-Belsen between 6 and 10 April 1945, each carrying approximately 2,500 prisoners from the death camp, destination another death camp, Theresienstadt.

The first train was liberated at Farsleben near Magdeburg, Germany by U.S. troops just a few days after departing Bergen-Belsen..

The second transport did reach Theresienstadt a few days later.

The third train — to become the lost train – left Bergen-Belsen on April 10, 1945.

This train would encounter up-close allied bombings, artillery firings between German and Allied troops, destroyed bridges, impassable routes, bombed out tracks and train stations, and constant danger of being mistakenly attacked by Allies or intentionally destroyed by the Nazis.

At one point, the Nazis considered dumping the entire train into the Elbe river.

As more and more prisoners died during the ordeal, fellow prisoners would bury the victims along the train tracks at each stop, “sometimes simply between two train stops.”

“Every evening we would remove the dead from the train and bury them beside the railway tracks,” recalls train survivor Mirjam (Andriesse) Lapid, who was 11 at the time.

In another interview in Through their Eyes, we learn more about the hellish nightmare.

This time from a conversation between young Dutch Ezra Soesan and his grandmother’s friend Anita Leeser-Gass, who was imprisoned at Bergen-Belsen along with her mother and second father.

Anita, who was seven at the time, tells how she and her mother – already sick, weakened and starved — are loaded onto the train that was to become de verloren trein (the lost train.)

“We had heard that they had built gas chambers in Theresienstadt,” Anita tells Ezra. “But on the way we ran into arms fire between the Allies and the Germans. We hung as much white clothing on the train as possible hoping that it would be clear to the Allies that we were not a military train…”

Anita tells how, during the shelling, the prisoners had to frequently step off the train and, together with the German guards, seek shelter under the train wagons.

Finally, on April 23, 1945, the doomed train comes to a halt near the little German town of Tröbitz where the prisoners are freed by the Russian Army. “By three Russians and a horse,” says Anita Leeser.

What followed were some dreadful days and weeks for the small mining community of 700 inhabitants “to which more than 2000 sick and starving people now came. Fast help was needed to save the half-starved and sick men, women and children and to ensure them a life in freedom,” according to a posting by the community of Tröbitz, commemorating the fateful event and quoting the words of German historian Erika Arlt.

A memorial stone at the Jewish cemetery in Tröbitz, “perhaps the only village in Germany where people of the Jewish faith have never lived in the past,” explains:

In memory of the Jewish men and women who succumbed to murderous fascism in Tröbitz in 1945, this stone was set as a reminder for the living.