About eight weeks ago we honored eighteen service members of the Jewish faith who have been awarded the Medal of Honor, going as far back as the Civil War.

One of those heroes is Corporal Tibor Rubin.

This is what we wrote about him:

Corporal Tibor Rubin [was awarded the Medal of Honor] for “for extraordinary heroism during the period from July 23, 1950 to April 20, 1953,” while serving as a rifleman in Korea where, among other, he “single-handedly defended a hill for 24 hours against waves of North Korean soldiers, securing a crucial route of retreat for his rifle company.”

Also, for “unyielding courage and bravery” while a prisoner of war for 30 months in a Chinese prisoner of war camp after he was severely wounded. Ruben is the only Holocaust survivor to be awarded the Medal of Honor. When he was thirteen, he survived 14 months at the Nazi Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

The full citation is at the end of this column.

When one honors eighteen Medal of Honor recipients in a short essay it is difficult to give each one the full credit they deserve.

Fortunately, on the occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah), Jon Guttman at The Military Times helps us to learn more about this hero.

On Rubin’s internment at a Nazi concentration camp:

Born in Pásztó, Hungary, on June 18, 1929, Tibor Rubin was 13 when the Nazis sent him to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. He survived 14 months before the U.S. Third Army liberated the camp. His family was less fortunate — his stepmother and sister died in Auschwitz and his father perished in Buchenwald.

Jon Simkins, also at The Military Times, describes this chapter in Rubin’s young life as follows:

Rubin, a Hungarian Jew, was seized by Nazi forces as a teenager while attempting to flee to neutral Switzerland. Following his capture, Rubin and his family came face to face with Dr. Josef Mengele, the diabolical SS physician often called the “Angel of Death” for his practice of inhumane medical experiments on Auschwitz prisoners.

“Dr. Mengele told us to go left or right,” Rubin told the Los Angeles Times in 2005. “If you went left, you went to a gas chamber. If you went right, you went to work in a labor camp.”

After emigrating to the U.S. in 1948, Rubin worked first as a shoemaker and then as a butcher in New York City, Guttman continues.

Fulfilling his promise that “if the Lord helped me go to America, I’d join the Army,” in July 1950, Rubin enlisted in the U.S. Army after failing the English language test a year earlier.

After shipping to Korea as a member of Company I, 8th Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, Rubin “discovered the persistence of American anti-Semitism…” Guttman writes. “This came particularly from his first sergeant, Arthur Peyton, “who made a policy of ‘volunteering’ him for the most hazardous missions…” he adds.

After two of Rubin’s commanders recommended him for the Medal of Honor, “both officers were subsequently killed and Peyton ‘lost’ the paperwork,” Guttman writes.

In the March 25 article on Jewish Medal of Honor recipients, we noted such prejudice and antisemitism towards servicemembers of the Jewish faith:

Even as Jewish men and women – more than 600,000 – have faithfully and patriotically served in every branch of our armed forces since the American Revolution, they have had to struggle against prejudice, constitutional bias and antisemitism and many have been denied high military honors.

Specifically, about Rubin:

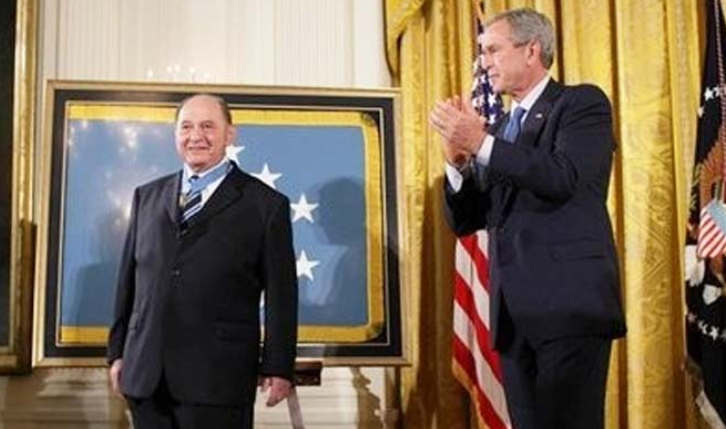

Take Holocaust survivor and Korean War hero Tibor Rubin. A 1993 study commissioned by the Army determined that Rubin had been denied the Medal of Honor because of religion. Fifty-five years after Rubin’s heroic actions, President George W. Bush presented Rubin the Medal of Honor.

But back to Rubin’s fate a prisoner of war in a Chinese camp.

Again, Guttman at The Military Times:

It wasn’t until April 20, 1953, that Rubin was released in a prisoner of war exchange. Although sick and weak, he claimed that Chinese treatment, harsh though it was, was a cakewalk compared to Mauthausen, from which he’d developed survival techniques that came into play again, such as stealing food and medicine from his captors or using maggots to treat gangrenous wounds, all of which he did for fellow POWs as “mitzvahs” (good deeds).

Learning that he was not yet an American citizen, the Chinese repeatedly offered to repatriate him to Hungary if he wished. Given the oppressive Communist regime there, Rubin declined.

In a tribute to Tibor Rubin at Army.mil, we get a glimpse at Rubin’s memories from the Nazi death camp and, later, from the Chinese POW camp:

Life as a prisoner under the Nazis and the Chinese are incomparable for Rubin. Of his Chinese captors, Rubin says only that they were “human” and somewhat lenient. Of the Nazis, Rubin remains baffled by their capacity to kill. He was just a boy when he lost his parents and two little sisters to the Nazi’s brutality. “In Mauthausen, they told us right away, ‘You Jews, none of you will ever make it out of here alive’,” Rubin remembers. “Every day so many people were killed. Bodies piled up God knows how high. We had nothing to look forward to but dying. It was a most terrible thing, like a horror movie…”

Tibor “Ted” Rubin became a U.S. citizen after he left the Army and settled in Long Beach California.

He passed away at his home in California on December 5, 2015. He was 86.

As mentioned earlier, in 2005, President George W. Bush presented him with the Medal of Honor. The citation below describes Corporal Tibor Rubin’s bravery above and beyond the call of duty.

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Corporal Rubin distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism during the period from July 23, 1950 to April 20, 1953 while serving as a rifleman with Company I, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division in the Republic of Korea. While his unit was retreating to the Pusan Perimeter, Corporal Rubin was assigned to stay behind to keep open the vital Taegu-Pusan road link used by his withdrawing unit.

During the ensuing battle, overwhelming numbers of North Korean troops assaulted a hill defended solely by Corporal Rubin. He inflicted a staggering number of casualties on the attacking force during his personal 24-hour battle, single-handedly slowing the enemy advance and allowing the 8th Cavalry Regiment to successfully complete its withdrawal.

Following the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, the 8th Cavalry Regiment proceeded northward and advanced into North Korea. During the advance, he helped capture several hundred North Korean soldiers. On October 30, 1950, Chinese forces attacked his unit at Unsan, North Korea, during a massive night-time assault. That night and throughout the next day, he manned a .30 caliber machine gun at the south end of the unit’s line after three previous gunners became casualties. He continued to man his machine gun until his ammunition was exhausted. His determined stand slowed the pace of the enemy advance in his sector permitting the remnants of his unit to retreat southward.

As the battle raged, Corporal Rubin was severely wounded and captured by the Chinese. Choosing to remain in the prison camp despite offers from the Chinese to return him to his native Hungary, Corporal Rubin disregarded his own personal safety and immediately began sneaking out of the camp at night in search of food for his comrades. Breaking into enemy food storehouses and gardens, he risked certain torture or death if caught. Corporal Rubin provided not only food to the starving soldiers, but also desperately needed medical care and moral support for the sick and wounded of the POW camp.

His brave, selfless efforts were directly attributed to saving the lives of as many as 40 of his fellow prisoners. Corporal Rubin’s gallant actions in close contact with the enemy and unyielding courage and bravery while a prison of war are in the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Army.”