The author is not quite as old as the “technique” mentioned in this article, but just admitting to having used it should be a dead giveaway to his age.

Tomorrow, May 24, is the 175th anniversary of the first Morse code message sent across a “long” distance over an experimental wire line — that is the 35 miles between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Md.

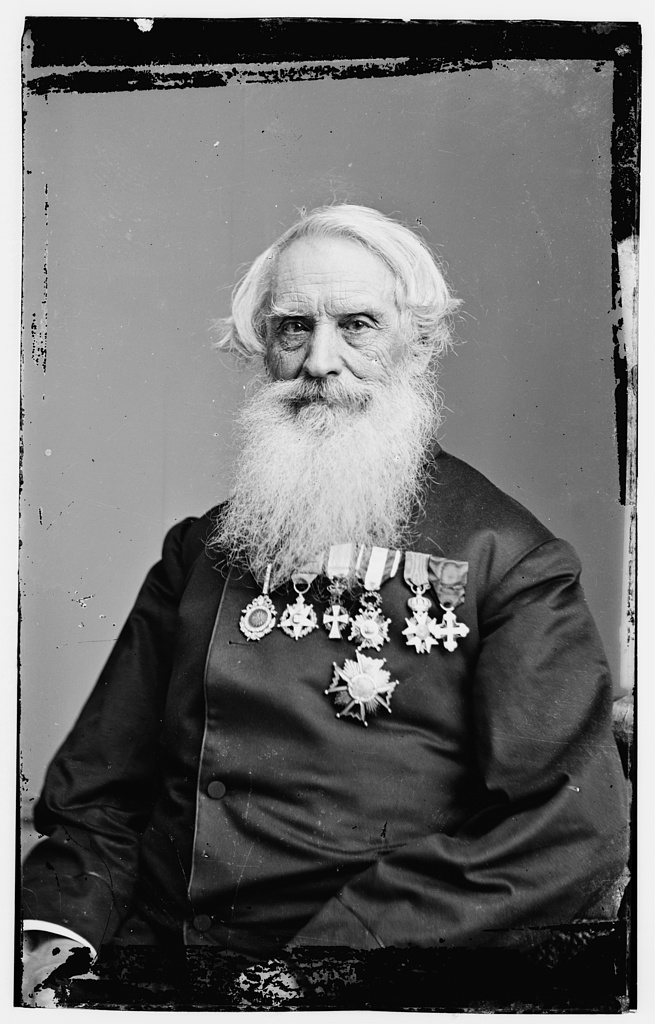

On that day, 175 years ago, Samuel F.B. Morse (one of the developers of the telegraph, below), used a code he had helped develop to send the historic message “What hath God wrought” and revolutionized long-distance communication.

Samuel F. B.Morse (Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress)

That code, modified and improved over the years, has come to be known as “Morse code” and, subsequently, along with the telegraph, has been used extensively around the world by governments, armies, commercial interests (e.g. “The Western Union Telegraphy Company”) and individuals.

For the young ones among our readers, Morse code messages are sent using a Morse code “keyer” and other electro-mechanical or electronic means via wire, cable or radio waves (“radiotelegraphy”) by representing characters through a combination of long and short electrical signals: dots and dashes (“dits and dahs”)

Already during the Civil War, both sides used Morse code to receive intelligence and to send “command and control” messages.

As a code that could be easily encrypted, securely and reliably transmitted, radiotelegraphy became the “preferred” means of military communication during World War II, especially for “carrying messages between the warships and the naval bases of the belligerents…using encrypted messages…used by warplanes, especially by long-range patrol planes that were sent out…to scout for enemy warships, cargo ships, and troop ships…”

During the Cold War, Morse code radiotelegraphy continued to be widely used.

As a U.S. Air Force airborne radio operator in the 50s and early 60s, the author became quite proficient at it for several reasons.

First and foremost, because of the excellent and intensive training the author received. So intensive that, 60 years later, he still finds himself almost unconsciously “tapping out,” with his fingers the Morse code for words he hears.

Second, because at times –- when, due to weather or equipment problems, all other means of communications failed aboard the mission aircraft — CW (continuous wave) Morse code communication became the only means to perform the mission.

Finally, as a young Hispanic immigrant (below) with quite a pronounced accent, when using voice radio communications, the use of “accent-neutral” Morse code became the favorite fallback means of communications for the author.

While the author was “just doing his job” as an airborne radio operator, there are many instances of bravery displayed by men and women in those roles. Their skills and actions in Morse code communication or Morse code intercept operations have saved lives, won battles and may have even won a war.

True, the use of Morse code is waning. In 2007, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission dropped Morse code as a requirement for all amateur radio technician class licenses.

However, the U.S. military still trains personnel in the use of Morse code (below), albeit not as extensively. Why? One military Morse code instructor points out, “We train [for] Morse code because the adversary still uses Morse code,” and another Air Force member says, “It remains the cheapest and most reliable means of communication.”

Students learn Morse code at the Center for Information Dominance (CID) Unit, Corry Station,Fla. “Morse code is just one tool that cryptologic technician (collection) Sailors use as members of the Navy’s Information Warfare community to perform collection, analysis and reporting on communication signals.” (U.S. Navy photo by Information Systems Technician 1st Class Kristin Carter)

True again. It is cheap, simple, reliable and it can be used to convey information in the most desperate, emergency situations (We all know how to “Morse-code-spell” SOS), whether via radio, smoke signals, flashing lights — or even with eye blinks.

That is exactly how Cmdr. Jeremiah A. Denton Jr., a Navy aviator shot down south of Hanoi in 1965 and captured by the North Vietnamese, conveyed to America the harsh truth about his captivity in a Hanoi prison.

The prisoner of war, tortured for 10 months by his North Vietnamese captors, was hauled in front of a Japanese television reporter in May, 1966, (below) for a propaganda broadcast and was threatened with more severe beatings if he did not respond properly to his interviewer.

During the interrogation, pretending to be blinded by the bright spotlights, Denton blinked out “T-O-R-T-U-R-E.” in Morse code with his eyelids.

It was the first confirmation that American prisoners of war were being subjected to atrocities during the Vietnam War.

Retired Rear Admiral Denton “whose public acts of defiance and patriotism came to embody the sacrifices of American POWs in Vietnam,” passed away March 28, 2014 at age 89.

This Memorial Day weekend, we remember and honor him along with all airborne, ground and intercept radio operators and all military men and women who have served their country and are no longer with us.

Lead image: U.S. Navy WW II recruiting poster.