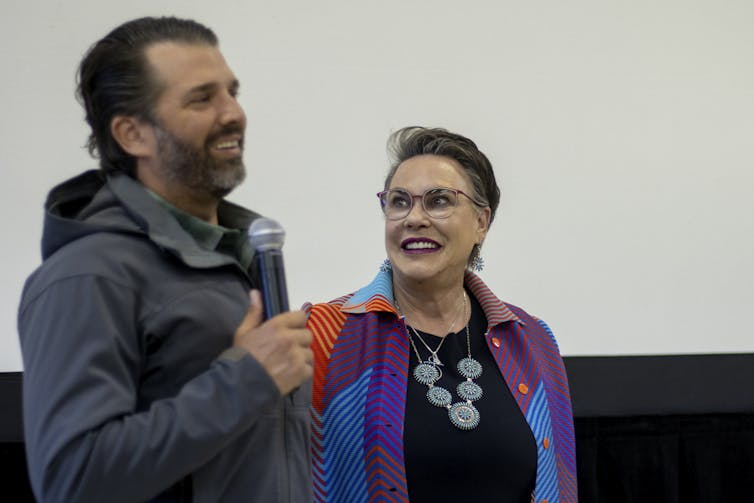

AP Photo/Jae C. Hong

Robert B. Talisse, Vanderbilt University

Republican Liz Cheney, a three-term member of Congress and the GOP’s leading – and lonely – critic of Donald Trump, lost her re-election bid on Aug. 16, 2022, to a Trump-supported primary challenger, Harriet Hageman.

Cheney had fallen out of favor with Republican voters across the country, who viewed her unrelenting sharp criticism of Trump as apostasy. Her fall from favor was dramatically evident in the Wyoming Republican primary, where Hageman took 66% of the vote to Cheney’s 29% share.

It was a stunning reversal of Cheney’s showing in previous years.

In the 2020 general election in Wyoming, Cheney won nearly 70% of the vote, based on her reliable voting record that was in step with the GOP legislative agenda.

In a state where over 70% of registered voters are Republicans, Cheney should have been a shoo-in for reelection in the Wyoming GOP primary. But she wasn’t.

Polling conducted 10 days before the election revealed Cheney trailing political newcomer Harriet Hageman by nearly 30 points.

The key difference between then and now is that Hageman has been endorsed by Donald Trump as a result of her embrace of Trump’s “big lie” that the 2020 election was “rigged.”

In stark contrast, Cheney remains one of the few GOP critics of Trump and serves as the vice chair of the Jan. 6 congressional select committee investigating the assault on the U.S. Capitol.

She has called Trump’s election lie “a cancer that threatens our great Republic.”

In response, Trump has called Cheney a “despicable human being” and a RINO, a pejorative acronym for “Republican in name only.”

The question then is how could the endorsement of a one-term, twice-impeached and historically unpopular former president catapult an unknown candidate into a massive win over an effective incumbent?

Partisan loyalty trumps GOP policies

As I argue in my recent book “Sustaining Democracy,” the situation is not so perplexing after all.

To explain Cheney’s predicament, it’s important to recognize that ordinary thinking about how democracy works begins with a mistaken premise.

Natalie Behring/Getty Images

We assume that voters first determine their interests and then support candidates who will best advance them. Although it lies at the heart of the theory of representative democracy, this assumption puts things backwards. In today’s hyperpartisan America, political interests are the product of political allegiances – not the other way around.

Partisan identity comes first, policy preferences trail behind.

Such is the case in Wyoming.

Judging from the animosity between the campaigns, it’s reasonable to expect stark policy differences between Cheney and Hageman. But in fact, their legislative priorities are very much alike. Hageman embraces standard GOP positions about protecting borders, opposing abortion, lowering taxes, upholding the Constitution and “putting America first” – as does Cheney.

By ordinary measures, Hageman and Cheney should be allies.

This happens because partisan affiliation is a matter of lifestyle rather than ideas.

In the United States, liberals and conservatives systematically prefer different neighborhoods, live in different kinds of housing and even demonstrate different tastes in home decoration.

Moreover, partisan identity is firmly tied to where one shops, the food one eats, the car one drives, the television shows one watches, where one vacations and even the brand of coffee one prefers.

Families, schools, workplaces and places of worship consequently have all become politically homogeneous.

With the electorate effectively segregated into distinctly liberal and conservative ways of life, partisan identity is acquired in the course of ordinary social interaction, similar to how individuals become fans of the local sports teams.

How extreme views develop

The trouble is that when individuals inhabit ideologically homogeneous social environments, they become increasingly vulnerable to belief polarization, the phenomenon whereby interactions with like-minded individuals lead us to adopt more extreme beliefs and attitudes.

As people become more extreme in this way, they also adopt intensely negative views of those who do not share their partisan affiliation. This causes them to band together with partisan allies, fueling the dynamic further.

Importantly, our polarized selves are also more conformist.

As people shift into more extreme beliefs and attitudes, they also demand increasing homogeneity among their allies. This renders coalitions more reliant on centralized and hierarchical leaders to set the standards for authentic group membership.

In turn, the group begins to expel members and thus to shrink.

Toxic impact on democracy

But that’s not all.

As the group becomes more homogeneous, it also becomes more vulnerable to the Black Sheep Effect, the tendency for individuals to dislike lapsed or deviant members of their own group more intensely than they dislike members of rival groups. Polarization makes cross-partisan relations toxic, but it also poisons relations among allies.

So Cheney’s political fate is no puzzle.

Ultimately, I believe, the difference between her and Hageman has little to do with legislative priorities or the business of Congress.

David Hume Kennerly via GettyImages

The divide, rather, is a matter of loyalty to a partisan identity that has Trump at its center, and the corresponding need to punish those who refuse to comply with his wishes.

Ironically, Cheney’s determination to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law may have been her undoing among Republican voters.

Yet the Wyoming primary reveals a deeper problem.

In the U.S. democratic system, members of Congress pledge to faithfully perform the role set for them in the Constitution. That role is to represent the interests of their state constituents in federal policymaking.

Once we recognize the centrality of partisan identities and how they are rooted in lifestyles rather than public policies, it becomes clear that much conventional thinking about how democracy works needs revision.

This story is an updated version of an article that was originally published on August 15, 2022.![]()

Robert B. Talisse, W. Alton Jones Professor of Philosophy, Vanderbilt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.