Royal Shakespeare Company Collection

Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Central Michigan University

Republicans, as you’ve probably heard, are being called “weird.”

In a quip that launched a million memes, Minnesota governor-turned-VP candidate Tim Walz referred to his right-wing political opposition as “weird people” in a July 23, 2024, interview on MSNBC.

Since then, the barb has stuck, with leading Democratic party figures, from Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer to presidential nominee Kamala Harris, branding their Republican opposition with the moniker.

Of course, in a classic deployment of the “I know you are, but what am I?” retort, the Republicans have tried to flip the script.

“You know what’s really weird?” Donald Trump Jr. opined on X. “Soft on crime politicians like Kamala allowing illegal aliens out of prison so they can violently assault Americans.” And in an interview with conservative radio host Clay Travis, former President Donald Trump said of Democrats, “They’re the weird ones. Nobody’s ever called me weird. I’m a lot of things, but weird I’m not.”

While I get why both sides are hurling weird bombs at each other, I’m nevertheless not on board with all the “weird shaming.” It isn’t just hypocritical for each party to claim to speak on behalf of the forgotten and marginalized while mockingly calling the other side weird. It’s also deeply regressive.

The weird, I would argue, deserve respect. As someone who has spent the past three decades researching, writing about and teaching topics including vampires, ghosts, monsters, cult films and what gets categorized as “weird fiction,” I should know.

‘Wyrd’ history

When politicians use the term weird, they’re trying to depict their opponents as odd or strange. However, the origins of the term are much more expansive and profound.

The Old English “wyrd,” from which the contemporary usage is derived, in fact was a noun corresponding to fate or destiny. “Wyrd” signified the forces directing the course of human affairs – an understanding reflected, for example, by Shakespeare’s three prophetic “weird sisters” in “Macbeth.” An individual’s “weird” was their fate, while use of the term weird as an adjective connoted the supernatural power to manipulate human destiny.

Despite the progressive generalization of the term to refer to all things strange, fantastic and unusual, resonances of the weird’s “wyrd” origins are retained by what has come to be called “weird fiction,” a subgenre of speculative fiction.

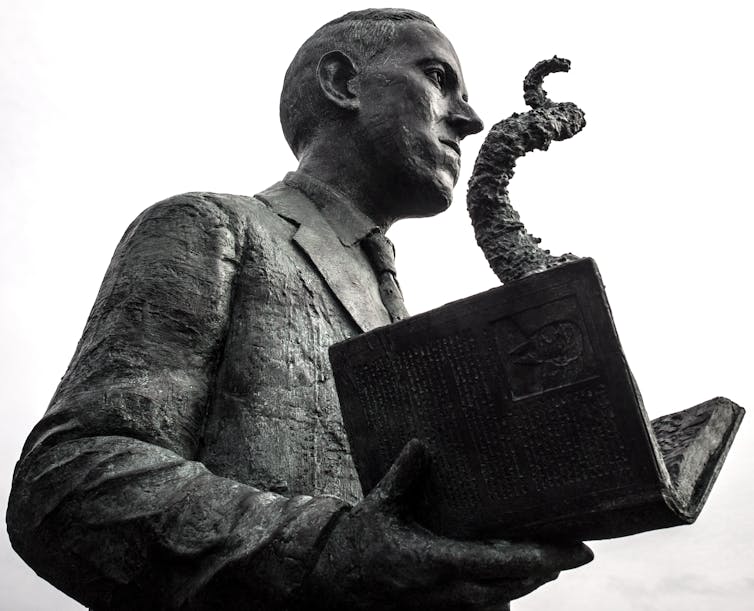

The weird tale, explained early 20th-century writer H.P. Lovecraft in his 1927 treatise “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” is one that challenges our taken-for-granted understandings of how the world works. It does this through – to use Lovecraft’s characteristic purple prose – a “malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguards against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

David Lepage/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The weird tale pushes back against human pretensions of grandeur, hinting at just how much we don’t know about the universe and just how precarious our situation truly is.

Meanwhile, the freaks, geeks, outsiders, misfits and mavericks are weirdos who push back in a different way. They are the nonconformists whom, as Ralph Waldo Emerson pointed out in his 1841 essay “Self-Reliance,” “the world whips … with its displeasure.”

Where would we be, I wonder, without the artists and scientists and thinkers developing “weird” ideas and unorthodox ways to see and appreciate the world?

In this sense, nearly all progress is part of weird history, propelled by visionaries frequently misunderstood in their own time.

From denigration to celebration

Of course, not all weirdos change the world through grand gestures and history-altering interventions; sometimes weirdos just do their own thing.

That, too, has been a large part of the story of the past century, as Western culture has increasingly – if reluctantly – made room for once-unorthodox or even taboo forms of self-expression, from tattoos to drag shows.

Proliferating subcultures, gender identities and forms of self-expression – although no doubt propelled by capitalist market forces – nevertheless demonstrate the premium placed today on individualism.

In fact, pop culture has been keen to invite historical weirdos back into the fold – so much so that vampires, ogres and fairy-tale villains such as Maleficent from “Sleeping Beauty” now enlist audiences’ sympathies by telling their side of the story.

The true villains are now often seen as those who demonize difference and insist on straight-jacketing individual freedom of expression. Many contemporary monsters aren’t bad, they’re just misunderstood – and their monstrous behavior results from being bullied, excluded, insulted and rejected for being “weird.”

Reclaiming weird

However sincerely felt, the Democrats’ deployment of the weird characterization is, of course, strategic.

Walz’s barb clearly managed to get under the skin of a crowd for whom the idea of not being “normal” is apparently distressing – and it is for this reason, I believe, that the Democrats have repeatedly tried to make the idea stick.

Historian of political rhetoric Jennifer Mercieca told The Associated Press, “The opposite of normalizing authoritarianism is to make it weird, to call it out and to sort of mock it.” Said another way, to refer to your opposition and their policies as “weird” is to denigrate it as abnormal.

Political expediency, however, comes with consequences – and here, much to my dismay, I find myself agreeing with Vivek Ramaswamy – the conservative entrepreneur who unsuccessfully ran for the Republican presidential nomination.

Ramaswamy wrote on X that the weird insults are “a tad ironic coming from the party that preaches ‘diversity & inclusion.’” Ironic puts it mildly.

While there may well be utility in deploying the term “weird” to frustrate political opponents, I’d prefer to reclaim the weird as something to appreciate, respect and celebrate.

The weird is that which introduces cracks into the edifice of the status quo, liberating possibilities for different futures and forms of expression. There are many different, more specific adjectives politicians and others can use to characterize their rivals.

Let’s keep America weird.![]()

Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Professor of English, Central Michigan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.