Crowds and critical thinking tend not to go hand in hand. That observation has been made by scholars throughout the centuries.

Take for example this passage from the 1914 work Cyclopedia of American Government:

“The conditions under which crowds gather are commonly unfavorable to reflective and critical thinking. Hence, it comes about that the level of intelligence to which successful appeal can be made is generally low. Political speakers often take advantage of this fact to employ analogies by way of argument such as would never for a moment stand the scrutiny of a calmer moment. . . In comparison with the normal individual consciousness, the mind of the crowd is fragmentary, discontinuous and especially susceptible to suggestions. It forgets the most evident facts, it leaps to conclusions over chasms of limitless depths, it follows with unbridled enthusiasm the leader who once holds it in his grip with little regard to rational continuity of thought.”1

The above-cited observation is affirmed by Psych Central author Rebecca Lee in her 2018 article The Acceptance of Group Mentality:

“Groupthink occurs when a crowd of people (usually with good intentions) conform in such a way that leads to dysfunctional or irrational behavior. Their viewpoints may be so strong that critical thinking becomes impaired and ration takes a back seat to the intensity of emotion rising from the group.”2

In his 1895 work The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, French psychologist Gustave Le Bon describes the relationship between crowds and reasoning:

“It cannot absolutely be said that crowds do not reason and are not to be influenced by reasoning. However, the arguments they employ and those which are capable of influencing them are, from a logical point of view, of such an inferior kind that it is only by way of analogy that they can be described as reasoning. . .

A chain of logical argumentation is totally incomprehensible to crowds, and for this reason it is permissible to say that they do not reason or that they reason falsely and are not to be influenced by reasoning. Astonishment is felt at times on reading certain speeches at their weakness, and yet they had an enormous influence on the crowds which listened to them, but it is forgotten that they were intended to persuade collectivities and not to be read by philosophers. An orator in intimate communication with a crowd can evoke images by which it will be seduced. If he is successful his object has been attained, and twenty volumes of harangues–always the outcome of reflection–are not worth the few phrases which appealed to the brains it was required to convince.

It would be superfluous to add that the powerlessness of crowds to reason aright prevents them displaying any trace of the critical spirit, prevents them, that is, from being capable of discerning truth from error, or of forming a precise judgment on any matter. Judgments accepted by crowds are merely judgments forced upon them and never judgments adopted after discussion.”3

Personal Observations:

– It is easier to use critical thinking while in a crowd when one has thoroughly studied the topic that a speaker is lecturing or preaching about.

– It is easier to use critical thinking while in a crowd when one has no emotional attachment to the speaker and/or other members of the crowd.

1McLaughlin, A.C., & Hart, A.B. (1914). Cyclopedia of American government. D. Appleton and Company.

2Lee, R. (2018). The Acceptance of Group Mentality. Psych Central. Retrieved on March 30, 2020, from https://psychcentral.com/blog/the-acceptance-of-group-mentality/

3Le Bon, G. (1895). The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. The Macmillan Co.

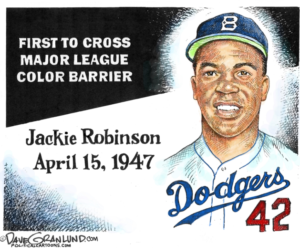

Featured Image from Library of Congress, in Public Domain.

The “Wanted” posters say the following about David: “Wanted: A refugee from planet Melmac masquerading as a human. Loves cats. If seen, contact the Alien Task Force.”