What some call a disability may be your greatest asset

by Dan Piraro

“Danny has a problem paying attention and following instructions,” read the damning note scrawled across my report card. My parents lectured me, but…I wasn’t paying attention.

Being different has always been stigmatized. Most of us outside the norm strive to “fit in.” But should we?

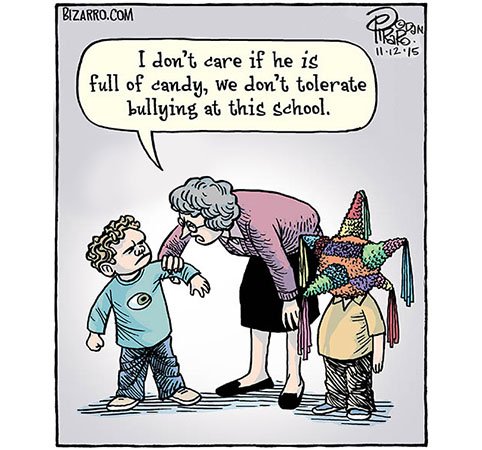

When kids are physically or mentally different from the average, they are often treated like threats or targets. Bullies abuse them, and adults often want to separate them from the “normal” children. When I was a kid, some were sent to stand in the corner as punishment when their behavior was deemed “disruptive.”

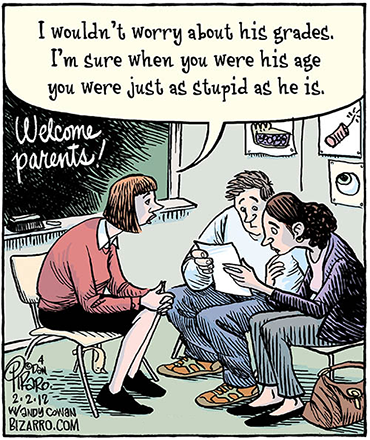

One of my sisters was dyslexic, but that condition wasn’t commonly known when we were young. Only two explanations were considered for children who had trouble reading: stupid or lazy.

My parents didn’t want a “stupid” kid, so they pushed her to try harder at something she was neurologically incapable of doing at that time. They may as well have been imploring her to levitate or speak Mandarin. That made her feel stupid, though she certainly was not.

I wasn’t dyslexic, but when I started school in the mid-1960s, sitting still and paying attention to a teacher was as unavailable to me as space flight. I could pay attention if I was doodling on a piece of paper as I listened, but that went over as well as if I’d tried juggling chainsaws.

I was far behind the other kids in learning to read, too. I was much more fascinated by the shape and design of letters than the sounds of them. Even after I got the hang of converting symbols to sounds, I could read an entire story and have almost no idea what it was about—the alternate stories simultaneously happening in my head demanded more attention.

Adding to my challenges was my family’s Catholicism. Dad had attended Catholic school, and it had toughened him up for Marine boot camp, so he did not want to deny me the same advantage.

My teachers were old-school nuns whose notion of compassion was to refrain from putting their full weight behind the yardstick they were swinging at our knuckles. Our school was connected to a church where my fellow students and I were required to attend mass every single morning, for an entire hour, presented in Latin.

Who brings a yardstick to church? Sister Mary Contusions did.

Sitting still under her watchful eye and listening to a man wearing a decorative shower curtain blather in a foreign language for an hour was torture for a kid like me.

To endure it, I would fall into my mind’s eye and let it wander far and wide. My mental adventures were just enough to get me through six years of five masses per week (and another on Sunday with my family!) without developing split personalities to bear the abuse.

Like many folks who can’t read, I used my wits to hide that I was so far behind the norm, and I found ways to make decent grades without reading the assigned materials.

The older I got, however, the more difficult that charade became.

After a lousy report card in middle school, my father insisted on helping me with my homework. When he saw the doodles all over my notebooks, he chided that I would never amount to anything if I didn’t stop drawing all over my schoolwork. I tried to explain it was the only way I could pay attention, but he was no more convinced than the old-lady nuns had been.

By the time I went to college, it was a lost cause. The assigned reading was too much and I dropped out after one semester.

It wasn’t that I didn’t know how to read, it was that I could not concentrate on what I was reading. I had to cover the same material over and over to comprehend it.

I lost count of how many lectures I’d heard on applying myself, but “not trying” was never my problem. I wasn’t behind the average because I was stupid or lazy—it was simply because I was not average.

In those days, society had yet to discover the obvious: Not everyone’s mind works the same way—and that’s okay.

Kids who learn differently are often called disabled, and shuttled off to a special school, or considered “slow” and placed in a remedial learning group. Worse yet, some are punished. I spent plenty of time standing in the corner. Humiliation did not cure me.

***

The concept of “learning disabilities” did not become mainstream until later, so I was never diagnosed, but I’ve always wondered if I had a few. I have long suspected I had ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) but have recently discovered I’m firmly on the autistic spectrum. You could have knocked me over with a feather.

My case is not as pronounced as it might’ve been, so I was not shipped off to an internment camp for fidgety slackers, but I experienced enough judgment to sympathize with anyone who is pigeonholed for not being like most people.

Capitalist societies need worker bees, and that’s what traditional education trains kids to be. But some folks are not suited for working in the hive, and that can make a person feel unfit, like an outsider who isn’t welcome to the party.

In my early adulthood, I lamented not being better at “normal” jobs (though these were jobs I didn’t want to do anyway!) but eventually, it was precisely my so-called “disorders” that enabled me to forge a successful career as a cartoonist.

Now in my sixties, I’ve written, drawn, and published over 12,000 cartoons in newspapers and magazines in the past few decades: one each day for almost forty years. And each time I’ve sat down to come up with a new gag, I’ve dropped into that place in my mind where I’d go as a kid during church each morning and tap into that creative flow—the same one that interrupted me when I’d try to read or listen to a lecture.

I have a theory why doodling allows me to pay better attention: Language and creativity operate from opposite sides of the brain. If I calm the creative side with drawing, it allows me to pay better attention to speech with the other side. When I look at those doodles later, I can remember what was being said when I created them.

For me, it is more effective than taking notes in English. (If only I could’ve drawn while reading!) But to this day, if I’m drawing, people assume I’m not paying attention.

That powerful, right-brain creative flow that refuses to be ignored and routinely inserts itself when I am trying to do something else is a symptom of my autism. But it is also the reason I’ve been able to adhere to such demanding cartoon publishing schedules.

What was labeled by the system as a “deficit” and a “disorder” turned out to be one of my greatest assets.

***

And my dyslexic sister who did poorly in school? She went on to manage a credit union, then later headed up her local Habitat for Humanity office, arranging financing and building homes for hundreds of low-income families in her community. Not so bad for a “stupid” and “lazy” kid.

As for my dad, he loves to tell the “if you don’t stop drawing all over your schoolwork” story on himself. He couldn’t be more proud of my career and laughingly thanks me for having ignored his fatherly advice.

He’s also lovingly apologized to my sister for misunderstanding her reading problems.

***

Most non-average behaviors are now called “neurodivergent,” which is a less judgmental and more accurate term than ADHD and the like—the Ds standing for “deficit” and “disorder.” “Neurodivergent” simply means a person thinks differently than is typical, and it’s no crime.

Know who else was different? Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, William Shakespeare, Abraham Lincoln, Charles Darwin, Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, Virginia Woolf, Steven Hawking, Toni Morrison, and Bruce Springsteen all displayed characteristics that were not average but proved to be why we know their names. Though I certainly don’t deserve to, I’d stand in the corner with those folks any day.

If you are neurodivergent—or socially, culturally, or physically different than the local norm—remember that you’re in pretty good company. Embrace your differences and the struggles they present, whatever they are. Use them, revel in them, display them with pride.

Our entire universe thrives on diversity: No two things anywhere are exactly alike. And here on Earth among humans, diversity is what makes history.

Dan Piraro is the creator of the syndicated newspaper and online comic Bizarro. His cartoons can be seen at bizarro.com. His creative writing can be subscribed to via bizarro.com/signup. To read his graphic novel Peyote Cowboy as it is being illustrated, see PeyoteCowboy.net