At this writing, 23,000 people on Twitter are applauding the Trump-Pence presidential campaign analogy comparing poisoned Skittles to Syrian refugees seeking asylum. In so doing, they are probably celebrating xenophobia but they are certainly highlighting impaired reasoning.

This image says it all. Let's end the politically correct agenda that doesn't put America first. #trump2016 pic.twitter.com/9fHwog7ssN

— Donald Trump Jr. (@DonaldJTrumpJr) September 19, 2016

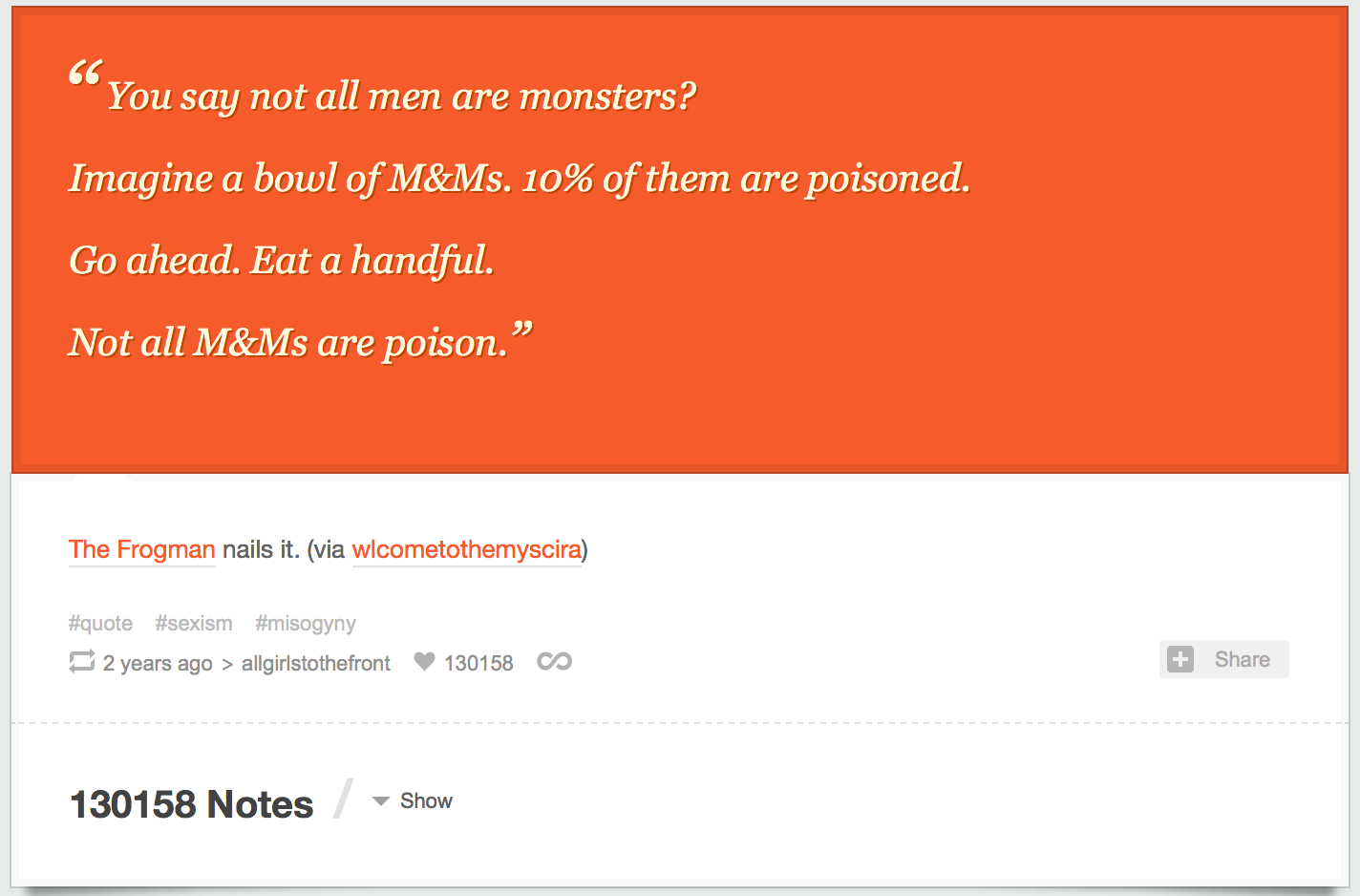

There’s nothing original about the Trump-Pence campaign Skittles analogy. In May 2014, Upworthy used its megaphone to trumpet this Tumblr post that makes a similar argument using M&Ms:

The Frogman is using sweeping generalizations (hyperbole) to criticize men who do not condemn violence against women.

Trump-Pence is relying on them to stimulate knee-jerk reactions.

The popularity of Monday’s tweet is a sad commentary on the state of American critical thinking skills. Or classic “us versus them” thinking. Or both.

The argument at the heart of the Trump-Pence meme is this:

Treating an entire group of people as suspect through an overgeneralization based on bigotry is as valid as not wanting to eat candy when you know, without a trace of doubt, that some pieces of the sample have been poisoned.

This argument is an appeal to emotion (fear) tied up with the hasty generalization, although there was nothing hasty about this tweet.

Where to start? Let’s begin with risk.

Is it possible for an event to be risk-free?

No.

I teach motorcycle safety classes, and one of our goals it to help students identify and minimize risk based on their own level of risk acceptance.

There’s a risk of dying if you get out of the bed in the morning. There is a risk of dying if you stay in bed all day.

Life is risk.

Based on the Trump-Pence analogy, which action should you take? Stay in bed or get out of bed?

Tylenol as the invisible foundation

In 1982, Johnson & Johnson pulled 31 million bottles of Tylenol from retail shelves and warehouses because three people died after taking a cyanide-laced Tylenol capsule. Seven people died from cyanide-laced capsules, although there were additional deaths from copycat crimes.

The Skittles analogy rests, unstated, on this infamous cultural event.

But even in 1982, there was no certainty that our bottle of Tylenol had been adulterated. In other words, the risk of swallowing a poisoned capsule was not the same as that outlined in the tweet.

Moreover, in 1982 on average about 120 people died each day from auto crashes. But no one was advocating that we pull cars off the street.

How many people die each year after consuming acetaminophen, the non-branded ingredient in Tylenol?

We don’t know, but it is more than seven. In 2013, ProPublica reported that the answer may range from the low 100s to as many as a thousand. What we do know is that in addition to reducing your own aches and pains, Tylenol seems to reduce empathy. And it’s the most dangerous OTC pain med:

Since 2006, acetaminophen has accounted for more fatalities than all other over-the-counter pain relievers combined, according to AAPCC data.

Do you worry about dying after taking Tylenol? Should you?

Risk assessment, our Achilles heel

In the Skittles-will-kill-you scenario, the meme-makers in the Trump-Pence campaign (Roger Ailes, anyone?) are letting our minds run wild regarding out chance of dying. How big is the bowl? Are there 100 candies in the bowl, for a 3-in-100 chance? Only 50? What are the odds?

Just as important, what is the benefit? An inconsequential gratification of a sweet tooth versus possible death.

But we know that our risk from accepting immigrants — refugees — is minimal. Vox exclaimed just last week (prescient, that September 13 headline) that Americans face very little risk from immigrants:

You’re more likely to be killed by your own clothes than by an immigrant terrorist. The odds of being killed by a refugee terrorist? One in 3.6 billion.

The Atlantic sang this song in June:

Americans Are as Likely to Be Killed by Their Own Furniture as by Terrorism. Terrorist attacks killed 17 U.S. civilians last year and 15 the year before.

But refugees? Their risk if unable to leave Syria is extreme.

Everyday decisions — whether to visit a neighbor, to go out to buy bread

— have become, potentially, decisions about life and death.

I applaud these attempts to contextualize risk. But the examples chosen — clothes, furniture — are unlikely to be heard by the innumerate. Here’s why.

Psychologists and sociologists (and probably a lot of other -logists) have pointed out ad nauseam that we humans have an outsized fear of rare events like plane crashes (and terrorist attacks), events that are statistically insignificant (unlikely to happen to us). But we believe that common events like heart attacks and car accidents (things more likely to happen to us, based on the odds) are less “risky.”

In the 1980s, psychologist Paul Slovic outlined several factors that lead us, the general public, to make such inaccurate risk assessments:

People tend to be intolerant of risks that they perceive as being uncontrollable, having catastrophic potential, having fatal consequences, or bearing an inequitable distribution of risks and benefits… Also unbearable in the public view are risks that are unknown, new, and delayed in their manifestation of harm…

Advertising executives have known this for years.

That’s why so many car ads are grounded in FUD: fear, uncertainty and doubt.

And political ads, like this one.

Because that’s what this tweet is: a political ad that — consciously, deliberately, with malice and forethought—exploits what we know about how humans assess risk and marries it to political action.

Moreover, the fact that an Illinois Tea Party Republican made the exact same analogy last month shows the derivative (without credit, naturally) nature of the Trump-Pence campaign. (Added: the photo appears to have been lifted from Flickr without permission; that photographer is a refugee.)

Hey @DonaldJTrumpJr, that's the point I made last month.

Glad you agree. pic.twitter.com/Nssw6KC1HY

— Joe Walsh (@WalshFreedom) September 20, 2016

America is a pretty darn safe place, one that is far more safe for white Christians than any other religious or cultural demographic.

In cases where the religious affiliation of terrorism casualties could be determined, Muslims suffered between 82 and 97 percent of terrorism-related fatalities over the past five years.

Trayvon Martin as an invisible foundation?

Finally, why change the meme from M&Ms to Skittles?

Because by November 2014, the M&Ms meme had been modified to focus on Syrian refugees.

In 2012, Florida became the nation’s epicenter for racial conflict when George Zimmerman shot and killed Trayvon Martin, who was returning home after visiting a nearby 7–11 for Skittles.

Since that time, Zimmerman has become a symbol of America’s “alt right” movement, previously known as white supremists.

In Trump, they found a candidate uniquely suited to the movement’s interests: funny, eminently meme-able, and promising to fix America’s worst problems through the sheer force of his will. Perhaps most important, they found a man willing to say the racist things no other mainstream politician would. As Trump steamrolled his way through the primaries, the newly emboldened alt-righters emerged as a force on social media. Among their targets were liberals (otherwise known as libtards), Jews, feminists, the media, and insufficiently reactionary conservatives, whom they called “cucks”…

Thus this tweet, which has generated reams of news coverage guaranteeing that its message is amplified far beyond the bounds of Twitter, was not written to persuade the undecided.

It was written to stroke, to reinforce existing support.

It is a predictable example of a campaign fueled by America’s alt-right.

It is a brilliant example of expedient, short-term political thinking designed to exploit known psychological potholes in reasoning.

And it is a chilling example of the emotions driving decisions about November 8th.

Known for gnawing at complex questions like a terrier with a bone. Digital evangelist, writer, teacher. Transplanted Southerner; teach newbies to ride motorcycles. @kegill (Twitter and Mastodon.social); wiredpen.com