This Presidential election cycle has been marked by one constant: how wrong many pundits and analysts have been who’ve insisted with great certainty that showman-businessman Donald Trump could NEVER get the nomination — just as many of them (and people in comments on blogs and Facebook) are now insisting he could NEVER be elected. Clearly, they have been wrong and could be wrong again. And what’s occurring with Donald Trump and those who solidly back him has even led brilliant historians such as historian-journalist Rick Perlstein to take pause and ponder not just what’s going on but how they perceived things and even see them now, even after painstaking research and careful analysis.

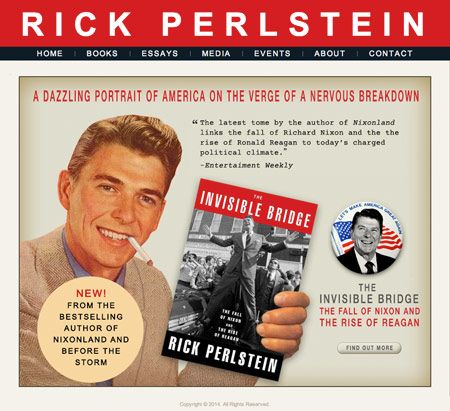

Firstly, if you don’t know Perlstein’s work and haven’t read his books you need to. He has traced the rise of American conservatism (and the decline of liberalism as an underlying background assumption in our media and political culture) in a series of books that started with 2001’s Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. After that came 2008’s Nixonland then, two years ago, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Each of his books reads like a novel: he offers huge quotes, reconstructs the political, media and cultural scene at the time (TV shows, movies, letters to the editor, state of the art research) and traces conservatism step by step becoming the dominant force in the Republican Party.

In an interview in Salon, he underscored how what we are now seeing is something totally different — something that doesn’t fit into past analyses. Here’s a bit of the interview that needs to be read in full, with a few comments (Ive added quotes to Pearlsteins’ answers):

Are you surprised that things seem to be turning up Trump?

“I had a very interesting experience this summer. I remember exactly when it was. It was when I was reading an article by [Evan] Osnos in the New Yorker about Trump. He happened to be covering the white nationalist movement, basically neo-Nazis. Coincidentally, it was right when Donald Trump burst onto the scene, and he wrote about how these guys were embracing Trump, as they never had embraced any Republican candidate before. The feeling I got was that this was the first time in a very long time that I’ve read anything about the Republican Party that I couldn’t assimilate into my normal categories. That was a very uncanny and uncomfortable feeling for me. I realized that I had to go back to the drawing board and rethink what was going on. This is something that’s very new, very strange, and very hard to assimilate into what we thought we knew about how the Republican Party worked.”

How has it changed your opinion of how the Republican Party works?

“Well, of course, the whole of my intellectual project, which I have been working on for a good, solid 15 years now, has been the rise of a conservative infrastructure that has taken over the Republican Party and turned it into a vehicle for conservative policy. If there’s one thing that I thought I knew, it is that basically the ideas and the institutions that were born through the Goldwater movement were a backbone of this conservative takeover of the Republican Party. Donald Trump is perhaps most interesting in his lack of connections to that entire world. The first sign that something very different was happening was when he basically rejected Fox News, threw them over the side, and had no interest in kowtowing to them.”

I’ve often noted here now the “givens” of our politics are crumbling. I also agree with The Daily Beast’s John Avlon and The Atlantic’s David Frum that part of the process that veered the Republican party sharply to the right and mad compromise a dirty words has been the the role of conservative talk radio and Fox News. They have been town-halls for modern conservatism and transmit a worldview, general perception, and provide often cherry-picked information to bolster listeners and viewers’ existing beliefs.

Who ever would have thought 40 years ago that entertainment for many Americans would be listening to someone bash one party or one ideology and name calling for three hours? The tribal tendencies of American partisan politics and ideology were reinforced. Next came the (less powerful) liberal entertainment political complex, which struggled to counter the conservative entertainment political complex. The talk radio/blog-comments-troll nature of our politics removed some constraints on out political discourse.

Trump has now removed other constraints on our political dialogue — constraints that I’ve always sensed came from the fact Greatest Generation politicos in general had lived through a century where the hate genie had been allowed to be released from the bottle and it was a terrible thing to bold, and a battle (at least partially) shove back in.

Pearlstein touches on this:

Do you think the things that Trump has been exploiting have always been exploitable, or do you think that some conditions, either in the Republican Party or the country at large, have changed and made Trump possible?

“That’s a good question. I think that people who base their political appeal on stirring up the latent anger of, let’s just say, for shorthand’s sake, what Richard Nixon called the “silent majority,” know that they’re riding a tiger. Whether it was Richard Nixon very explicitly, when he was charting his political comeback after the 1960 loss, rejecting the John Birch Society. Or whether it was Ronald Reagan in 1978 refusing to align himself with something called the Briggs Initiative in California, which was basically an initiative to ban gay people from teaching, at a time when gays were being attacked in the streets. Or whether it was George W. Bush saying that Islam is a religion of peace and going to a mosque the week after 9/11. These Republican leaders have always resisted the urge to go full demagogue. I think they understood that if they did so, it would have very scary consequences. There was always this boundary of responsibility, the kind of thing enforced by William F. Buckley when he was alive.

I think that Donald Trump is the first front-runner in the Republican Party to throw that kind of caution to the wind. As demagogic as so much of the conservative movement has been in the United States, and full of outrageous examples of demagoguery, there’s always been this kind of saving remnant, or fear of stirring up the full measure of anger that exists.”

There are no such reservations anymore. Is it generational? He notes:

“But, by the same token, for a lot of these people growing up, the experience of Europe, and World War II, and fascism, was a living memory. I think there was this kind of understanding that civilization can often be precarious. I think people knew that, and people saw that, and as ugly as some of these folks could be, whether it was Ronald Reagan going after welfare queens, or Richard Nixon calling anti-war protesters “bums,” or George W. Bush basically engineering a conspiracy to get us into a war in Iraq, there was a certain kind of disciplining, an internal disciplining. I think that anyone who plays the game of American politics at that level knows this can be a very ugly country, that a lot of anger courses barely beneath the surface.

Let me tell you a story about Barry Goldwater. One of the first big things to happen in America, after the Republican convention that nominated Barry Goldwater, in which he of course, famously said, “Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice,” was the outbreak of a very frightening race riot in Harlem, in New York. As I wrote in my first book, people who were rioting in Harlem were rioting, of course, in response to the shooting of a black young person by a white cop. Barry Goldwater kind of stuck his finger in the air and said, “This is really frightening stuff.” He actually, in a meeting with Lyndon Johnson, literally said, “If my supporters start exploiting these riots and start exploiting racial turmoil in the United States to get me elected, I will withdraw from the presidential campaign.”

That’s a profound contrast to someone like Donald Trump, who literally began his campaign by proposing one of the most massive ethnic cleansings in the history of mankind. I mean, can you imagine what it would mean? People talk about Bernie Sanders’ program being radical and inconceivable. Can you imagine what would happen in the act of trying to deport 12 million human beings, if people start resisting?

And — unlike many of the talking heads on TV, or bloggers on any number of blogs, right and left — he admits that trying to find thoughtful explanations isn’t easy:

If Trump is defeated, do you think the Republican Party can right itself, or do you think Trump has opened up a permanent wound?

“[Pauses.] Let the record show that I’m speechless. I have no easy answers for this one. What would it mean to right the ship? You have some very profound and fundamental problems. You have every senator who has ever worked with Ted Cruz turning toward Donald Trump, because they can’t stand Cruz. You have much of the infrastructure of the conservative movement explicitly saying that Donald Trump is unacceptable. That’s a pretty profound breach, especially for liberals who are so used to seeing conservatives and Republicans as united strategic geniuses. Again, I have to end on that note of humility. Where was the original contradiction? Where did this come from? Is it, you know, really just this one guy with big hair? Is this situation the result of the failure of political economy as practiced by the Democrats and the Republicans? I don’t have any good answers, and anyone who does, I think, is being glib.”

Read the interview in full since he also comments on Jeb Bush’s flameout.

But mostly read the books. They are written in a highly lively style where you don’t only get to see the growth of conservatism but he virtually reconstructs the entire era in his use of quotes and research of news events, films, media reaction, and original research. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED:

Joe Gandelman is a former fulltime journalist who freelanced in India, Spain, Bangladesh and Cypress writing for publications such as the Christian Science Monitor and Newsweek. He also did radio reports from Madrid for NPR’s All Things Considered. He has worked on two U.S. newspapers and quit the news biz in 1990 to go into entertainment. He also has written for The Week and several online publications, did a column for Cagle Cartoons Syndicate and has appeared on CNN.