Seymour Hersh wonders, should we be worried about a cyber war?

The short answer, NO!

The amount of cyber-jargon we’ve got in government is stupefying: A Cyber Czar rules Cyber Command assessing the cyber threat to our cyber security; we need cyber weapons to defend against a cyber attack, protect against cyber-pillaging and wage cyber war; we must develop cyber capabilities able to withstand sustained cyber operations… to say nothing of the cyber-crime threat from cyber-criminals.

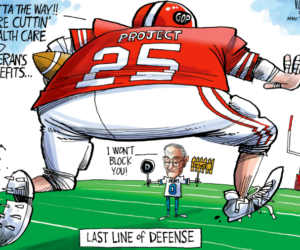

And in the end Hersh suggests it’s bureaucrats building political support for their expanded turf and former government officials building sales for their books. The piece begins and ends with the first international crisis of George W. Bush’s Administration — a crisis caused by a lack of political leadership and military commanders unable to ever give up a mission.

A couple snippets. First, a fundamental confusion:

I was told by military, technical, and intelligence experts that these fears have been exaggerated, and are based on a fundamental confusion between cyber espionage and cyber war. Cyber espionage is the science of covertly capturing e-mail traffic, text messages, other electronic communications, and corporate data for the purpose of gathering national-security or commercial intelligence. Cyber war involves the penetration of foreign networks for the purpose of disrupting or dismantling those networks, and making them inoperable. … Blurring the distinction between cyber war and cyber espionage has been profitable for defense contractors—and dispiriting for privacy advocates.

The most common cyber-war scare scenarios involve America’s electrical grid. Even the most vigorous privacy advocate would not dispute the need to improve the safety of the power infrastructure, but there is no documented case of an electrical shutdown forced by a cyber attack. And the cartoonish view that a hacker pressing a button could cause the lights to go out across the country is simply wrong. There is no national power grid in the United States. There are more than a hundred publicly and privately owned power companies that operate their own lines, with separate computer systems and separate security arrangements. The companies have formed many regional grids, which means that an electrical supplier that found itself under cyber attack would be able to avail itself of power from nearby systems. Decentralization, which alarms security experts like Clarke and many in the military, can also protect networks.

What about Stuxnet?

If Stuxnet was aimed specifically at Bushehr [nuclear-energy plant, in Iran], it exhibited one of the weaknesses of cyber attacks: they are difficult to target and also to contain. India and China were both hit harder than Iran, and the virus could easily have spread in a different direction, and hit Israel itself. Again, the very openness of the Internet serves as a deterrent against the use of cyber weapons.

Bruce Schneier, a computer scientist who publishes a widely read blog on cyber security, told me that he didn’t know whether Stuxnet posed a new threat. “There’s certainly no actual evidence that the worm is targeted against Iran or anybody,” he said in an e-mail. “On the other hand, it’s very well designed and well written.” The real hazard of Stuxnet, he added, might be that it was “great for those who want to believe cyber war is here. It is going to be harder than ever to hold off the military.”

The image is of a proposed Air Force Cyber Command patch that caused something of a flap in 2008 because of its similarity to the Strategic Air Command patch. I find nothing about the patch since.