In 2011 America will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War. If the last two 50-year markers are any indication, this will be a very big deal.

States across the country are starting their preparations. Here in Tennessee, which saw more military action than any state outside Virginia, a coalition of preservation, tourism and education groups is preparing for the event. Scholars have planned a symposium next month for the anniversary of John Brown’s Raid at Harper’s Ferry, an event that played a crucial role in triggering the war.

But what will this mean for American identity? Historian David Blight outlined three memorial narratives that emerged in the decades following the Civil War. The Emancipationist narrative, embraced by African Americans and the dwindling population of white Radical Republicans emphasized the promise of freedom to four millions slaves as the single most important event in the war. The Lost Cause narrative insisted that the South was justified in seceding, that its troops fought honorably and nobly, that slavery was ancillary at best to the cause of secession – “state’s rights” were the REAL reason for secession – and the Old South social order was superior to what followed. Then there was the Reconciliationist narrative, which praised white soldiers North and South for the bravery and dedication to cause – though no serious examination of causes should be undertaken so as not to disturb the fragile peace.

In 1911, the Lost Cause narrative had triumphed – especially in the South. Nearly every Southern town had a statue of a Confederate soldier gracing its most conspicuous public space. Reconstruction was written into the textbooks as an infamous era of black supremacy and corruption. And the first blockbuster feature-length film in American history – Birth of a Nation – celebrated the Ku Klux Klan, which re-emerged in 1915 as the final statement of Lost Cause values for a new age.

By 1961 the Reconciliationist narrative had come to dominate national discourse. This was the moment when modern re-enacting and battlefield preservation really took off. The early civil rights movement had done enough to temper the old fires of Lost Causism – among Northerners especially – but it had yet to eradicate this white supremacist narrative. In fact, many Southern states revived their Lost Cause heraldry as a relic of Massive Resistance to the civil rights movement; Georgia even added the Confederate Battle Flag to its state flag at this time. Still, the centennial of the Civil War was a time to celebrate both sides and, as much as possible, ignore the causes that led up to it.

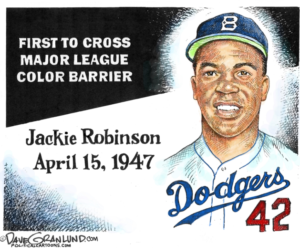

The 1960s changed all of that, and reignited support for the Emancipationist narrative. Civil rights activists openly identified with Radical Reconstruction, and black Civil War soldiers were “rediscovered” by white people – and valorized in the movie Glory. Even white Southerners – now in migration to the Party of Lincoln – grudgingly accepted the emancipation of slaves as a fundamentally positive moment in American history (though many continued to insist that secession was over “state’s rights” and not defense of slavery).

How will this play out in the sesquicentennial celebration? With the election of a black President America has made its most profound statement on the consequences of the Civil War. Expect lots of self-congratulation on how far we’ve come as a nation – thanks largely to the Union victory, the emplacement of civil rights in the Constitution during Reconstruction (even if it would take another century before those Amendments had any meaning), and, of course, the valor of the soldiers.

But that doesn’t mean the emancipationist narrative will go uncontested. Scholars on the left have long challenged the motives of Radical Republicans, seeing them more as agents of industrial capitalism than moral avatars of freedom. If the great myth in the South is that secession was based on state’s rights, the great myth in the North is that most of the soldiers fought to free the slaves (and the Underground Railroad was proudly supported in every Northern town). This delusion of self-congratulation belies a Northern racial conservatism that made emancipation far from inevitable.

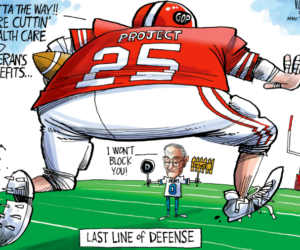

On the far right will be the Neo-Confederates who insist that they fought against Federal tyranny; no doubt they will incorporate current day gripes against the Obama Administration as part of their revived Lost Cause.

And millions of others will just want to visit the beautiful battlefield parks, imagine themselves to be soldiers and officers, and think nothing beyond platitudes of the reason they fought.

Hopefully, though, we will come out of the sesquicentennial with a more nuanced understanding of what Union, freedom and, yes, race, actually meant for Americans in 1861.