[icopyright one button toolbar]

A suggestion for a national holiday?

Make the Confederacy’s Defeat a National Holiday

Brian Beutler / The New Republic— 150 years ago this week, Robert E. Lee surrendered to the Union. Let’s celebrate it—every year. — In a speech one month ago, the first black president of the United States challenged millions of white Americans to resist the convenient allure …

Good thought, but jumping the gun on today, in many ways, the REAL end of the Civil War.

The Daughters of the Confederacy are hallucinating on that “almost” line.

At the end of the last day that the Army of Northern Virginia would ever fight, Robert E. Lee surveyed the disaster. Of a force of barely 30.000, 8.000 had been lost in a single, disastrous engagement:

Upon seeing the survivors streaming along the road, Lee exclaimed in front of Maj. Gen. William Mahone, “My God, has the army dissolved?” to which General Mahone replied, “No, General, here are troops ready to do their duty.” Touched by the faithful duty of his men, Lee told Mahone, “Yes, there are still some true men left … Will you please keep those people back?” [Wikipedia]

In the end, Robert E. Lee was betrayed by logistics: at the fall of Richmond, he had requested that rations be sent by rail to Amelia Court House, about thirty miles to the west of the fallen Confederate capital. When the troops reached the Court House rail junction on April 4th, there were supplies waiting, but it was all ordnance. Lots of it, in fact.

Macon State Park North Carolina, recreation of Confederate rations storeroom

But no food. In the panic of evacuating the capital, the message never reached the Confederate Commissary General, and no food was waiting for the exhausted, wet and dispirited remnants of the once-mighty Army of Northern Virginia. Lee was forced to send out foraging wagons, to literally beg for whatever food might be got. As the wagons returned, there was little if any provender, and Lee had fatally lost his one day’s head start on the Army of the Potomac.

The retreat had also been stymied by April showers, which had lifted the rivers and streams of the coastal plain that defines Richmond and the surrounding countryside to near flood levels. One crossing was impassable, and an alternate, which was supposed to be crossed by pontoon bridge also proved impossible because (logistics, again) the pontoons had never arrived at the crossing.

Lee lost a fatal day that way, without gaining any advantage and only starving his exhausted troops further.

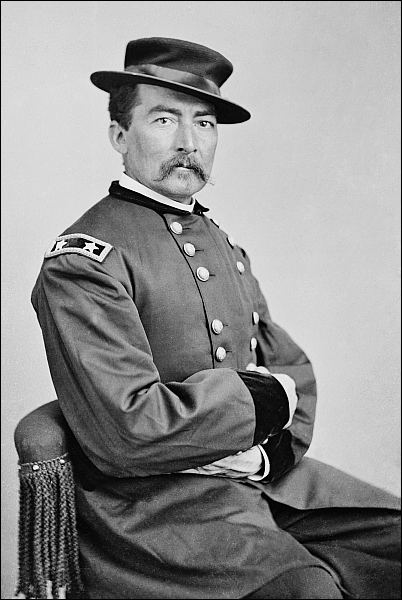

Sheridan was in hot pursuit, as were the II and VI Corps. And then, George Armstrong Custer managed to be, once again, as at Gettysburg, in the right place at the right time.

General Philip Sheridan

For various reasons, one-third of Longstreet’s corps became separated from the main body. Evidently, they had seen the Federal cavalry, and stopped, to make a stand against attack, but the Federals didn’t attack. But Ewell lost an hour’s march.

Custer saw that, and positioned his cavalry between Ewell’s corps (there are details I’m skipping here) and the main body of the retreating army.

This is where logistics betrayed Lee’s army for the last, and probably worst time.

Remember all that ordnance? Ewell, realizing that Custer was about to attack sent the precious wagons north, to evade the battle that seemed imminent, Earlier, Custer had captured a lightly guarded wagon train of supplies, including Confederate artillery ammunition.

As supporting troops came up to reinforce the Federal cavalry, a unit of Federal artillery set up on the hill and began slicing the Confederates to pieces,

Though they still had the guns, the Confederate artillery had no ammunition.

Shorn of various details, the bottom line was this: the Confederate commanders began to surrender. Eight generals and eight thousand men, and guns, artillery, and huge portion of the supplies that the Army of Northern Virginia had left.

They’d marched for food and got only ammunition. Now without food, when the ammunition was needed, they didn’t have that, either.

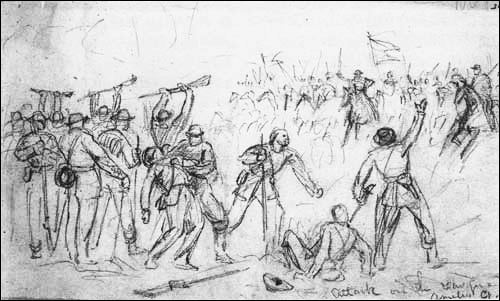

Civil War battlefield artist Alfred Waud sketched this surrender

of Ewell’s corps at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek. Waud’s drawings would

be courier’ed to New York, where woodcut artists, like Thomas Nast

would translate them into woodcuts for the newspapers. Nast would

sometimes sign them as “Thos. Nast” rather than credit “Alfred Waud.”

Nobody realized it yet, but the battle of Sailor’s Creek (which was actually three separate engagements that happened nearly simultaneously, but which were unconnected militarily, save, perhaps, in a thematic sense) was the last time that the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia would ever face each other. For the South, it was an unqualified disaster. For the bumbling Army of the Potomac, who had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory so often before, it was a smashing victory that left no doubt as to the final outcome of that most vicious tug of war over the seventy miles between Washington D.C. and Richmond, Virginia.

It had been Lee’s plan to make it to Danville, railroad South into North Carolina to join with Johnston’s forces and continue the war,

Now, that was impossible.

Lee would think about it for a couple of days, but on the ninth he would surrender at Appomatox Court House. And with that surrender, the steam would come out of the Southern cause. There were a few more battles, but the loss of Robert E. Lee and his army was the death knell for the South and everyone knew it The desperate gamble had failed, finally, to pay off, and the Army of Northern Virginia would huddle forlornly on wet and soggy ground in the rain for two days until surrender — AND RATIONS! — appeared.

This was the last meaningful day of the American Civil War.

THE SKIRMISH NEAR AMELIA COURT HOUSE

AS SKETCHED BY ALFRED WAUD. (Library of Congress)

And, as noted, Lee was betrayed by logistics in the end: you can have the best army, the best tactics and the best strategy, but without bullets and butter, it all comes to naught,

At the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Major General George Washington Custis Lee, Robert E. Lee’s eldest son, would see his first combat of the war, and then he would surrender, after a war spent in garrison duty in Richmond, away from the fighting.

And this image, which perhaps sums up the force of nature that the Army of the Potomac finally became under Ulysses S. Grant and Phil Sheridan, courtesy of History Net (whose recounting I urge the reader to click on and read — really one of the best online histories of this fateful day 150 years ago):

Custer ready for his 3rd charge at Sailors Creek 1865, Alfred Waud sketch

The general [Ewell] surrendered himself and his staff to a cavalry officer, who then had a note from Ewell forwarded to Custis Lee, informing him that he was cut off and suggesting that to prevent further loss of life he should surrender. In all, the Federal attack had bagged six Confederate generals and more than 3,000 men.

Farther to the south, meanwhile, Merritt’s cavalry prepared for their mounted attack against Anderson’s Confederates. Some of the Union troopers, having previously worn out their usual mounts during the campaign, had acquired mules to ride in their stead. One rider remembered: ‘It took my mule just about four jumps to show he would outclass all others. He laid back his ears and frisked over [the] logs and flattened out like a jackrabbit….He switched his tail and sailed right over among the rebs, landing near a rebel color-bearer of the 12th Virginia Infantry…a big brawny chap and he put up a game fight, but that mule had some new side and posterior uppercuts that put the reb out of the game.’ (Originally appeared in Civil War Times magazine, by Chris M. Calkins)

Spanish-American War officer on a mule (1898)

In another bit of historical farce, the battle is often reported as the “Battle of Saylor’s Creek” and was even designated as such by the USGS body empowered to name stuff, but historians have found that, no, it’s a typo. It was “Sailor’s Creek” at the time, but the typo remains enshrined in present day atlases, maps and gazetteers, and, because of such, many histories.

Retreating with Ewell’s corps was a group of Confederate sailors (unshipped, obviously), just to add irony to the debacle of Sailor’s Creek.

This was the last day, the last battle, the last glimmer of forlorn hope for the Lost Cause. Lee’s army was whipped. After four long years, from First Bull Run to Sailor’s Creek, two great armies had mauled each other horrifically, staining nearly every inch of the road between Washington and Richmond with the blood of Americans. And like the Welsh Red Dragon, the Army of the Potomac had triumphed after long sufferance.

The Army of the Potomac, sketch by Waud, as it appeared in final form,

in Harper’s Weekly, bearing his ‘signature.’ Click to enlarge.

The last soldier killed in the war would be Private John J. Williams of Jay County (Eastern) Indiana–who may well be a distant relative of mine, since my brood had originally settled there but then moved in the next generation to northern Indiana. Private Williams died in Texas in the last skirmish of the war, which the South won.

The long national nightmare is nearly over, but April of 1865 held one more unspeakable horror in the Good Friday to come.

Here’s “10 Facts About Sailor’s Creek“, from the Civil War Trust. And some information on preserving the battlefield.

The normally placid Sailor’s Creek had risen above its banks,

choked by April rains, and was between two and four feet deep,

as many soldiers found out the hard way.

Courage.

This is cross posted from his vorpal sword.

Hart Williams has been a journalist and author for nearly four decades. He has written for innumerable publications, from the Washington Post and Kansas City Star to Locus Magazine and The Tutuveni, the Newspaper of the Hopi Tribe.

A writer, published author, novelist, literary critic and political observer for a quarter of a quarter-century more than a quarter-century, Hart Williams has lived in the American West for his entire life. Having grown up in Wyoming, Kansas and New Mexico, a survivor of Texas and a veteran of Hollywood, Mr. Williams currently lives in Oregon, along with an astonishing amount of pollen. He has a lively blog, His Vorpal Sword (no spaces) dot com.