Everyone knows the old saw, attributed to George Bernard Shaw, “Britain and America are two countries, divided by a common language.” [icopyright one button toolbar]

Fortunately, there is a simple formula for translating between them: the British understate, while the Americans overstate. (The word, “Everyone” in the preceding paragraph is a nice example of the latter.)

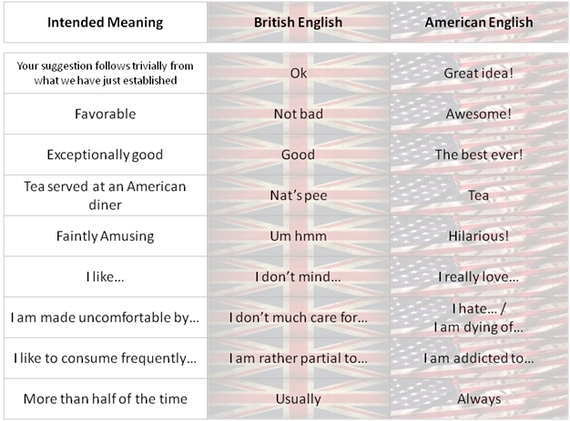

If a Briton finds something to be good, he will declare it “not bad”. An American will declare it to be “awesome”. A translation table between the two cultures could therefore include,

“Good (Actual) = Not Bad (Brit.) = Awesome (Amer.)”

It’s an easy enough formula to grasp, but sometimes it’s not an easy difference to bear.

My first experience of corporate America was a month of staff training in Palo Alto for a consulting company that I joined as my first job out of university. Some time into the month, one of the company’s partners was giving a speech to the new staff, and, during the question and answer session, someone indicated that it was lunch time. A little later, the speaking partner suggested “let’s go and get some food”.

Another partner, standing across the room, declared this “a great idea”.

After a couple of weeks of exposure to such overstatements, my English ears had taken just about as much of this abuse of the language as they could take and, risking getting fired before I had begun my first day on the job, I foolhardily blurted, “That isn’t a great idea. General relativity was a great idea. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle — also a great idea. Having lunch: not great and probably not even an idea”.

I lasted a couple of years in the job. Considering how I started, that wasn’t bad going. (And there is an example of British understatement.)

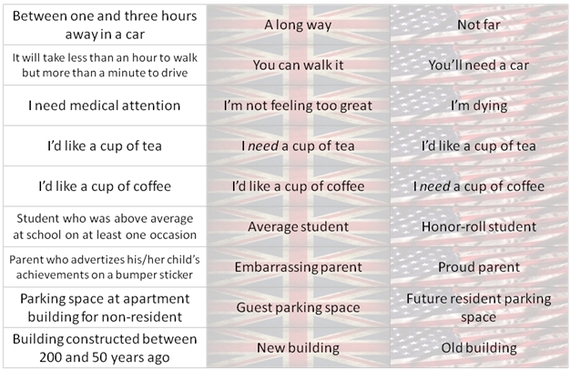

About four years later, I was back in the States, and found myself visiting someone in an apartment complex. Upon arrival, I drove around the parking lot, looking for guest parking. They had none. I ended up putting my vehicle in a “future resident parking” space.

I told my friend what I had done and asked to where I should move the vehicle. And from his confused response — that I should leave it exactly where it is — I learned that in the USA, it’s ok to lie for marketing purposes, as long as those lies are also overstatements, of a kind.

I will soon have been living in the USA for 10 years, at which time I shall be eligible for citizenship, which I will be proud to take. The idea of being proud to be part of a nation is decidedly unEnglish but extremely American and so, I hope, stands as proof of my enculturation. During this last decade, I have been learning by osmosis American English — or rather, the American use of English — and, while still far from bilingual, I can understand most of what I hear.

So for the benefit of those Brits who may come after me as new Americans, and for the benefit of any American friends and British family who may have to communicate with each other at my citizenship ceremony’s after-party, I offer the following British-American translation table — with a special bonus table for my political friends.

Call it my contribution to the Anglosphere.

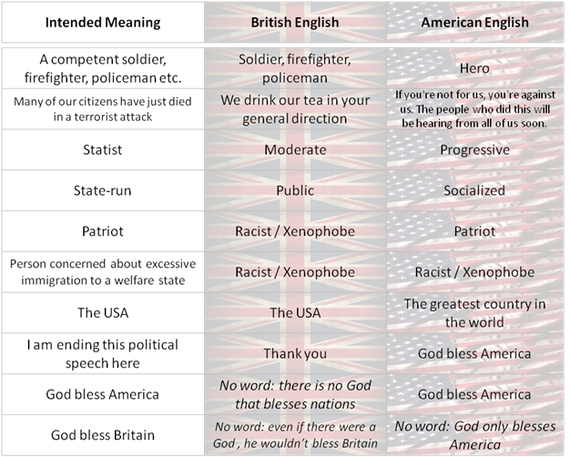

And here’s the bonus for my political friends…

Robin Koerner is a British-born citizen of the USA, who currently serves as Academic Dean of the John Locke Institute. He holds graduate degrees in both Physics and the Philosophy of Science from the University of Cambridge (U.K.). He is also the founder of WatchingAmerica.com, an organization of over 100 volunteers that translates and posts in English views about the USA from all over the world.

Robin may be best known for having coined the term “Blue Republican” to refer to liberals and independents who joined the GOP to support Ron Paul’s bid for the presidency in 2012 (and, in so doing, launching the largest coalition that existed for that candidate).

Robin’s current work as a trainer and a consultant, and his book If You Can Keep It , focus on overcoming distrust and bridging ideological division to improve politics and lives. His current project, Humilitarian, promotes humility and civility as a basis for improved political discourse and outcomes.