If you’ve ever visited Normandy, where the American-led freedom crusade launched the multifaceted assaults that ultimately vanquished fascism, you surely know – as I’ve just learned – that nouns and verbs and adjectives can’t begin to encapsulate the experience. I won’t even try.

Last week, I found that it was sufficient, on the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, to commune with our resting heroes in the American cemetery on the eastern end of Omaha Beach, and reflect on what it meant to be an American when America was at its best.

At home these days I feel nothing but shame, thanks to the fascists who are trampling our traditional verities and doing their very worst, but on this verdant patch of northwestern France I feel nothing but pride. We are loved over here for what we did so selflessly – American flags festoon front yards at every turn – and I can only hope the locals’ long memories, their fervent gratitude, will continue to trump whatever concerns they may harbor about a treasured ally that has lost its mind.

But I need to point out the pride I feel here is intertwined with sorrow. The cold statistics – 9,389 U.S. soldiers are interred in the aforementioned cemetery, spread over 172 immaculate acres suffused in birdsong. The names of 1,557 soldiers missing in action are emblazoned on a semicircular wall – subsume the human dimension.

Each of those kids (average age 24) had a family back home and was just a few years removed from high school sock hops and soda fountain meetups before metastasizing fascism on faraway soil hijacked their budding lives. To see a marble headstone bearing the name of a kid killed on the very first day, barely off the boat, prompted me to reflect on the hard years of training that preceded his one fateful moment.

Wilbert F. Lucka of New Jersey, a private in the 26th Infantry, I salute you.

I learned, too, about a lieutenant from Pennsylvania who was long believed to be missing forever, and whose name was thus etched on the MIA wall – until he was unearthed from a mass grave that he shared with Nazi soldiers. Which was particularly grotesque, because the lieutenant was Jewish.

Nathan Baskind, I salute you.

I learned about a U.S. Ranger from California who had just completed a grueling commando training course in Scotland, famous for its brutal hill runs and use of live ammunition, capped by weeks of amphibious landings along the English coastline. On D-Day this lieutenant made it to the sand on Omaha Beach after struggling through the surging waves. He ran toward the sea wall but machine gun fire snuffed his last conscious instant.

Robert Brice, I salute you.

I learned about one of Brice’s Ranger comrades, a sergeant from Pennsylvania who was celebrating his third wedding anniversary on D-Day. Shortly before landing on Omaha, his buddies sang songs to celebrate the occasion. Minutes later he was cut down. He is not interred in Normandy, but his widow, who survived him by 58 years, requested that she be buried beside him.

Walter Geldon, I salute you.

And I thought about Mildred Reed, a wife and mother from Manhattan, Kansas. Her husband Ollie and her son Ollie Jr. rest side by side in Normandy. The junior Ollie, an Army lieutenant, was killed in Italy on July 6. The senior Ollie, an Army colonel, was killed in Normandy on July 30. Mildred learned of her husband’s death and her son’s death in separate telegrams that arrived at her home 45 minutes apart.

Needless to say, I salute her too.

None of these Americans were “suckers” and “losers.” They answered the call because they took it on faith that their country was good and that whoever was president would follow the Constitution. I bet they never could’ve imagined a time when a president, queried as to whether he’ll honor our founding document, would respond by saying “I don’t know.”

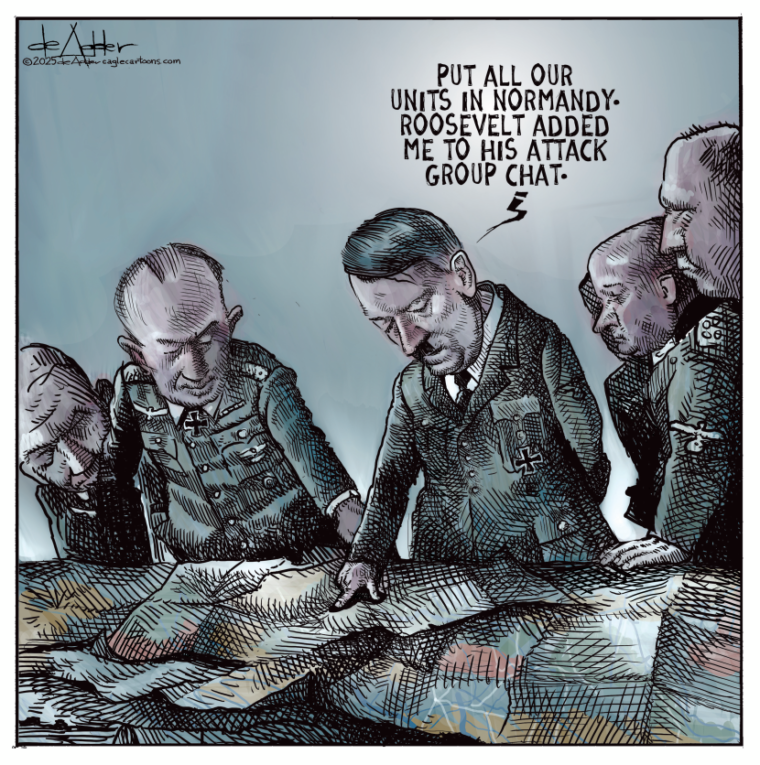

On V-E Day, our Normandy guide, a font of historical wisdom named Marie, quoted the philosopher George Santayana, who famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Marie thinks that’s an apt remark, “given what we see going on in the world.” I think it’s especially apt given that a certain individual is too stupid to have even learned of the past, much less to have drawn any lessons from it.

Now the fight against fascism has reached our shores. We who recognize this existential threat must ensure that those who died for democracy did not do so in vain.

Copyright 2025 Dick Polman, distributed exclusively by Cagle Cartoons newspaper syndicate. Dick Polman, a veteran national political columnist based in Philadelphia and a Writer in Residence at the University of Pennsylvania, writes the Subject to Change newsletter. Email him at [email protected]