David Eulitt/Getty Images

Aarushi Bhandari, Davidson College

This fall, I’ve been starting my sociology classes by asking my students to share some uplifting news they’ve come across.

On Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2023, they were abuzz about Taylor Swift’s appearance at the Kansas City Chiefs game on Sunday. Swift and Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce had left Arrowhead Stadium together in Kelce’s convertible, confirming dating rumors.

As a scholar of the attention economy, I wasn’t exactly surprised. Many of my students love Swift’s music, and the story had dominated major social media platforms like X, formerly known as Twitter, as a trending topic.

But I was taken aback when I learned that not a single student had heard that the Writers Guild of America had reached a deal with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, or AMPTP, after a nearly 150-day strike. This historic deal includes significant raises, improvements in health care and pension support, and – unique to our times – protections against the use of artificial intelligence to write screenplays.

Across online media platforms, the WGA announcement on Sept. 24, 2023, ended up buried under headlines and posts about the celebrity duo. To me, this disconnect felt like a microcosm of the entire online media ecosystem.

Manufacturing consent online

It almost goes without saying that news and social media platforms promote some stories and narratives over others.

This particular occurrence is fascinating, however, because the AMPTP represents some of the media conglomerates that directly disseminate news. For example, CNN is owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, a member of the AMPTP.

At the time of this writing, CNN.com has three headlines about the WGA strike and eight headlines about Swift at the Chiefs game.

Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s 1988 book “Manufacturing Consent” outlines the problem of media ownership by conglomerates. According to this theory, powerful interests control narratives, in part, by owning news sources.

There’s a free press in the U.S. But Herman and Chomsky argue that the news that reaches everyday people tends to be framed by a set of assumptions that align with the ideological interests of the media corporations and their advertisers: maintaining the economic status quo and spurring consumerism.

In the U.S. today, six conglomerates own and control 90% of media outlets.

Per Pew Research Center data, a majority of Americans get their news from online sources. Scholars have since adapted Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model to explain how social media ecosystems function.

The role of algorithms is a key focus of emergent research on manufacturing consent online. Sociologist Ruha Benjamin’s work consistently shows that algorithms are encoded with their developers’ biases. Other studies show that critiques about algorithmic biases are suppressed by corporate digital media platforms through strategies like shadow-banning, which refers to covertly banning users of concern without their knowledge. These algorithms determine what is trending on websites like X. This, in turn, influences trends on other platforms, like Google searches.

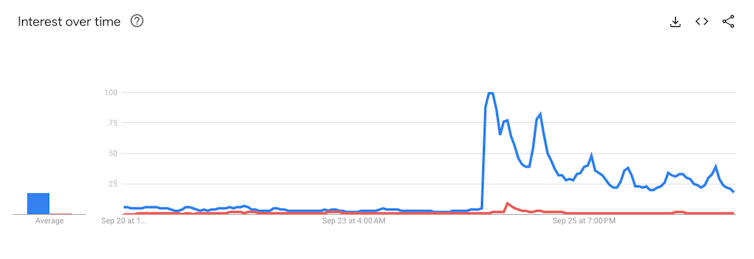

Google trend results show an enormous increase in search queries about Travis Kelce since Sept. 20, 2023, with the WGA strike victory receiving almost no interest in comparison. The massive gap in interest between these topics serves as an example of algorithms supporting trending topics over other newsworthy content.

Aarushi Bhandari/Google Trends, CC BY-SA

Another key focus of the propaganda model for social media is targeted advertising.

Unlike their predecessors in television, social media companies use “big data” to know users intimately and present ads that are personalized to each user. This strategy includes guerrilla marketing techniques like the ones employed by several companies after Swift’s appearance.

For example, the National Football League changed its X bio to read “NFL (Taylor’s Version).” Sales of Kelce’s jersey skyrocketed in the few days after Swift’s appearance at the Chiefs game. Hidden Valley Ranch changed its X handle to “Seemingly Ranch” after a Swift fan account noted that during the game, Swift had dipped her chicken fingers in “seemingly ranch.”

Corporate media coverage of labor issues

The muted coverage of the writers strike fits into a longer historical pattern of tension between labor movements and corporate media.

In many cases, corporate media has framed disproportionately negative narratives about strikes and union activities.

For example, an analysis of media coverage of tensions between the United Auto Workers and General Motors from 1991-93 found that major newspapers, including The New York Times, consistently framed GM’s position in a positive light, while crafting significantly more negative stories about the strike and autoworkers. Similar patterns are visible in media reporting on the 1993 American Airlines flight attendant strike and the 1997 United Parcel Service strike.

When not covering labor issues in a negative light, corporate media has a track record of ignoring and minimizing these issues. Communications scholar Jon Bekken’s meta-analysis of media coverage discovered substantial drops in coverage of labor issues by major outlets like the Chicago Tribune, The New York Times and CBS throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century.

This historical dynamic is beginning to change. Increasing public support for labor unions and worker action have made it difficult to ignore the bubbling currents of organized labor across many industries, from Starbucks to autoworkers.

Today, 58% of Americans support the ongoing United Auto Workers strikes against GM, Ford and Stellantis, the company that makes Chrysler, Jeep and Dodge vehicles.

Despite corporate ownership and biased algorithms, labor movements have managed to secure public support, demonstrating that Americans are increasingly aware of their own class interests. During such a fraught political climate for the economic status quo, the WGA victory is a major indicator that strikes work.

So, amid these tensions, a feel-good story about Taylor Swift and football is a gift to media executives – and one that helps sell more ranch dressing, too.![]()

Aarushi Bhandari, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Davidson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.