Update II:

Jelani Cobb at The New Yorker has an excellent piece about Dr. Carson’s gaffe in particular:

This is roughly akin to arguing that it is technically possible to refer to a kidnapping victim as a “house guest,” presuming the latter term refers to a temporary visitor to one’s home.

But more importantly, about Carson’s previously displayed “propensity for gaffes during his maladroit Presidential candidacy,” and how such a phenomenon might be “a stand-in for a broader set of concerns about the Trump Administration”:

[T]he reluctance to countenance anything that runs contrary to the habitual optimism and self-anointed sense of the exceptionalism of American life.

Read it all here.

Update I:

This is not the first time Ben Carson has referred to Africans, who were cruelly and sometimes violently torn away from their families and homes to become slaves to Americans, as “immigrants.”

He did so in his 2000 book, “The Big Picture,” and in his 2012 book, “America the Beautiful,” not only referring to them as “immigrants,” but also repeating his claim — in slightly different language — that these “immigrants” came to America so that their children and grandchildren might pursue freedom, opportunity and happiness in their new land.

Original Post:

Speaking to his Housing and Urban Development (HUD) staff of Monday, the newly confirmed HUD Secretary painted a glowing picture about the hopes and dreams of our first “immigrants” from Africa as they sailed to the “land of dreams and opportunity.”

Having heard and read different stories about the circumstances surrounding the recruitment and transportation of these passengers and of their reception and fortunes in the land of dreams and opportunity, I decided to check it out.

And lo and behold there is some merit to Dr. Carson’s remarks, worthy of the “prolonged standing ovation,” he claims he received from his audience.

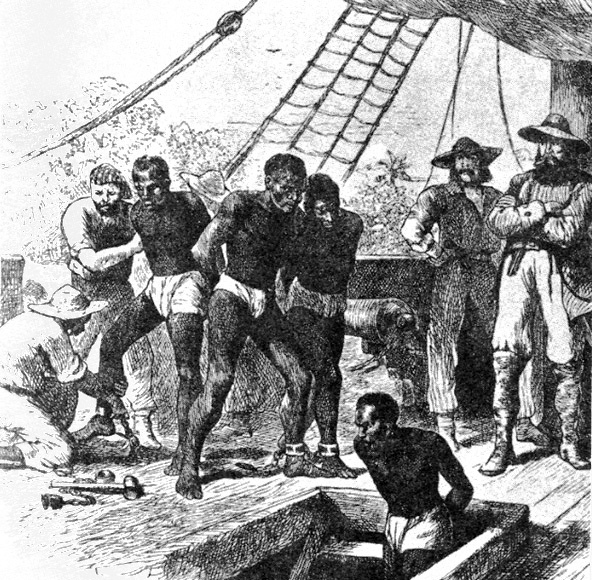

The nearly 12.5 million African immigrants who sailed the Atlantic — called the “Middle Passage” — to the promised land spent several weeks aboard ships owned by companies with romantic names such as the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa — companies first dominated by the Portuguese, and then taken over by more experienced British and American companies.

Some of the ships were home-away-from-home to as many as 700 passengers and some even included luxuries such as portholes for better airflow to the lower decks.

The fare for such a voyage was modest even for those days, sometimes as low as £5 to £6 per passenger and, best of all, the fares were paid by others.

During the leisurely six-to-eight-week Atlantic crossing, passengers had plenty of time to dream about what to expect in the promised land, to dream about “that one day their sons, daughters, grandsons, granddaughters, great grandsons, great granddaughters might pursue prosperity and happiness in this land.”

Upon their arrival at ports in South Carolina, Virginia and elsewhere, the new immigrants had the opportunity to see firsthand free trade in action in the New World. A “free trade” that in today’s terms would be worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Finally, we are all familiar with how these immigrants fared in their new home.

Also on Monday, after his glowing description of the hopes and dreams of those “immigrants who came here in the bottom of slave ships, [who] worked even longer, even harder for less,” Carson backtracked somewhat and referred to them as “involuntary immigrants.”

There are numerous writings on the shameful period in American history, writings where these unfortunate “immigrants” are called by their real name and their story is told in less idealistic terms.

One of them is “Slave Ships and the Middle Passage,” contributed by Brendan Wolfeby.

Please read it here.

Lead image credit: https://www.flickr.com/