AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

Lincoln Mitchell, Columbia University

Democrat Dianne Feinstein, the 90-year-old senior senator from California, died on Sept. 28, 2023.

Feinstein had an extraordinary political career that began when she won her first election only a few months after Neil Armstrong walked on the Moon.

Then came the day that changed Dianne Feinstein and her hometown of San Francisco forever and made her a national figure.

On Nov. 27, 1978, Feinstein, then the 45-year-old president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and two-time failed mayoral candidate, greeted reporters at City Hall by telling them she would not seek reelection to the Board of Supervisors, San Francisco’s equivalent to the city council.

This was understood to mean she was leaving politics when her term expired. The resignation of one person from the 11-member board earlier that month had given Mayor George Moscone an opportunity to put a progressive on the board, tipping the balance to 6-5 against Feinstein in her bid to retain leadership.

Feinstein’s plan didn’t last long. By the end of the day, she was the mayor of San Francisco, and had the dreadful responsibility of telling the city that both Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk had been assassinated – by a former member of the board.

“It is my duty to make this announcement,” she said, looking straight into the camera, amid audible gasps and screams, adding, “The suspect is Supervisor Dan White.”

Feinstein handled this tragic announcement with poise – a quality that would characterize the nine years she went on to spend as San Francisco’s first female mayor and, later, as California’s first woman senator.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein

Even though Feinstein was a fixture in Washington, D.C., for more than three decades, San Francisco was always her home.

“When you become mayor because of an assassination and the horrific events that catapulted Feinstein into the mayor’s office, you will be forever linked to that city,” says Corey Busch in 2022, Moscone’s press secretary and an advisor on Feinstein’s campaign when she ran for mayor in 1979.

Feinstein was not from the San Francisco of hippies, new tech wealth, radical politics or LGBTQ activism. She was born to an affluent Jewish family and attended the Convent of the Sacred Heart, the city’s elite Catholic girls school. Feinstein’s mother was emotionally distant, according to her biographer Jerry Roberts, but she was close with her father, a prominent doctor who encouraged her ambition.

Underwood Archives/Getty Images

Feinstein won her first election to the Board of Supervisors in 1969 after serving several years on the state women’s parole board. She remained on the board until that dreadful day in November 1978.

As mayor, living primarily in tony Pacific Heights and Presidio Heights, Feinstein led the city through a tumultuous time of change. The period between 1978 and 1987 included Mayor Moscone’s assassination, the horrors of a mysterious plague – HIV/AIDS – cutbacks in state and federal funding and a panoply of urban problems like crime, traffic, homelessness and rising rents.

During that same period, San Francisco went from being a somewhat typical American city to becoming a major politically progressive hub. That transformation left the city deeply divided. Feinstein was able to govern it by combining social liberalism with strong support for business, development and real estate.

This kind of urban governance – later exemplified in Michael Bloomberg’s 12-year mayorship of New York City – is pretty common now. But Feinstein was one of the first politicians to embrace it, and her leadership from the center frequently angered San Franciscans who believed she was not doing enough about AIDS, or was too close to real estate interests, or just wasn’t sufficiently progressive.

“Feinstein was very supportive of gay people that she knew,” Art Agnos, the mayor after Feinstein, told me, “but struggled to relate to LGBTQ equality as an abstract civil rights issue.”

In lefty San Francisco, “a lot of people think that Dianne is more suited as a moderate Republican than as a Democrat,” said Busch, Feinstein’s former campaign advisor.

For me, as Feinstein’s teenage constituent, it was her crackdown on the punk music scene – which frequently included allowing the police to harass punks attending shows at venues like the Mabuhay Gardens, which was usually called the Mab – that bothered me. When I was 16, I climbed the flagpole in front of her stately and expensive house to amuse my friends. There’s a photo of this caper in my high school yearbook.

Mayor Feinstein’s generally conservative demeanor was also a target of our teenage derision – and other people’s as well. The legendary San Francisco columnist Herb Caen occasionally called her “Princess Di,” a reference to Feinstein’s formal, even imperious style.

Bettmann/Contributor via Getty

Feinstein’s legacy

After leaving the San Francisco mayor’s office in 1987, Feinstein ran for governor of California in 1990. She lost to Republican Pete Wilson, but in 1992 won a special election to the U.S. Senate.

As senator, Feinstein’s moderation sometimes frustrated progressives in the Democratic Party, as it had her hometown constituents.

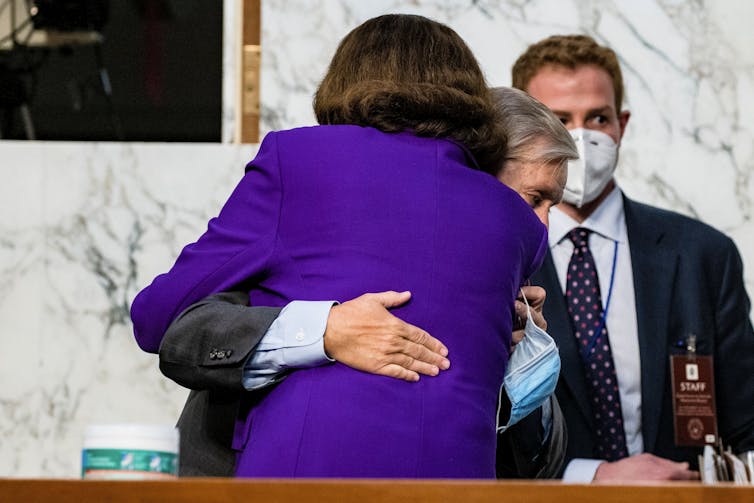

She voted for the war in Iraq in 2002 and for George W. Bush’s major tax-cutting legislation in 2001. In 2020, she literally embraced the Republican Sen. Lindsay Graham of South Carolina at the conclusion of Amy Coney Barrett’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

Samuel Corum / POOL / AFP via Getty

But Feinstein was well liked, an electoral powerhouse and a generally reliable Democratic vote on major legislation long before California took on its current political shade of deep blue. She supported the Affordable Care Act, voted against Donald Trump’s tax bill in 2017 and opposed all three of Trump’s Supreme Court nominees. She has also been a committed fighter for California’s economic interests, from winemaking to desert conservation.

In her last reelection to the Senate, in 2018, the 85-year-old Feinstein brushed off the kind of progressive primary challenge that felled other moderates in her party to win her fifth full term in office.

She had announced her intent to retire in 2024, at the end of her current term, in the face of growing concerns about whether she still had the cognitive abilities required of a U.S. senator.

This issue was raised not by Republicans seeking to score political points, but also by Democratic colleagues and congressional staff. Her death requires California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who considered Feinstein a mentor, to appoint her successor.

Feinstein was a trailblazer and one of the most successful women in American political history, but not one of its greatest senators. Feinstein was never connected to a singular important issue, as the late Ted Kennedy was with health care. Nor did she author any landmark legislation, as John McCain and Russ Feingold did with their namesake 2002 campaign finance reform bill. Her greatest legislative accomplishment remains her work on the assault weapons ban in 1994.

During a career that lasted almost 50 years in public office, her leadership after the City Hall killings remains Feinstein’s finest moment in politics – the one that made her long career possible. For San Franciscans of a certain age, she will forever be known as the woman who stepped in at one extraordinary and tragic moment and helped us believe our city would survive.

This story is an updated version of a story published on Feb. 14, 2023.![]()

Lincoln Mitchell, Associate Adjunct Research Scholar, Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies, Columbia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.