on an all-expense-paid trip to the Soviet Union

Donald Trump has sworn innumerable times since the Russia Scandal reared its hydra head that he has no connection to Russia, now or ever. In fact, Trump is one big Russia connection.

Beginning in 1984, over 30 years before he ran for president, Trump began tapping into what would become an extensive network of contacts with corrupt businessmen, mobsters and money launderers from the former Soviet Union, Russia and their satellite states to make deals ranging from real-estate sales to beauty pageants sponsorships to bailing out his frequently ailing enterprises.

It is tempting to say that Trump built that network himself as his business empire grew, but in reality members of the network more often used him as a convenient patsy. This has been especially true of money launderers.

In 1991, the Soviet Union fell and President Boris Yeltsin ordered the dramatic shift from a centralized economy of state ownership to a market economy, enabling cash-rich mobsters and corrupt government officials to privatize and loot state-held assets. After Vladimir Putin succeeded Yeltsin, Russia’s feared intelligence agencies joined forces with mobsters and oligarchs, and Putin has given them free hand so long as they help enrich him and strengthen his grip on the country.

Then in 1998, Russia defaulted on $40 billion in debt, which accelerated the exodus of money. By one estimate, some $1.3 trillion in illicit capital has poured out of Russia in the last 25 years, including many tens of millions of dollars that flowed into Trump’s luxury developments and Atlantic City casinos, which were used as convenient pass-throughs for laundering illicit riches.

It is not an exaggeration to say that dirty Russian money saved Trump, if only barely.

By the late 1990s, he owed $4 billion to more than 70 banks, with $800 million of it personally guaranteed. “But fortunately for Trump, his own economic crisis coincided with one in Russia,” writes Craig Unger in “Trump’s Russian Laundromat,” a recent New Republic story.

Only traces of Trump’s network can be found in his financial disclosure statements, and since his businesses are all privately held and he has refused to release his federal tax returns, his business relationships with Russians are not readily apparent.

But we do know that Trump has ventured aggressively into the former Soviet empire since his financial recovery, frequently cutting deals with bottom feeders, and at one point sought to have his name affixed atop a massive glass tower in Astana, the post-Soviet capital of Kazakhstan. He also has done business with companies that have violated U.S. sanctions against Iran and applied for a trademark in that country, which he has tried to isolate as president.

Now, as president and commander in chief, Trump makes policy decisions that have the potential to positively affect his 565 Trump Organization holdings in the U.S. and abroad, and his oft-stated determination to weaken sanctions against America’s greatest foe has resulted in a rare bipartisan agreement (by a 98-2 Senate vote, no less) that sanctions should be strengthened, not watered down.

All of this begs a very big question.

Trump’s layering of lies upon lies in refusing to acknowledge his Russia ties and continued insistence that the Russia scandal is a “hoax,” which he yet again reiterated in tweets over the weekend, is a reflection of the frightening fantasy world in which he dwells. But it also may be a consequence of members of the network being able to leverage Trump’s literal and figurative debts to them — if not blackmail him outright.

“Without the Russian mafia,” says Unger, “it is fair to say Donald Trump would not be president of the United States.

Indeed. And the list of people who have the goods on Trump surely includes the ruthless Vladimir Putin, in whose presence the other day he was notably obsequious. This is because of his biggest Russia connection of all — the cyber plot to sabotage Hillary Clinton and make him president.

in the gilded rococo penthouse at Trump Tower

The crown jewel of Trump’s business empire is Trump Tower, a 58-story glass and marble edifice at 721-725 Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan that opened in 1983 when Trump was a 38-year-old tabloid celebrity developer.

According to federal investigators and journalists who have dug into Trump’s wheeling and dealing, at least 13 people with known or suspected links to Russian mobsters or oligarchs have owned, lived in, and even run criminal enterprises out of Trump Tower and other Trump properties. This has been made easier because Trump has accepted anonymous buyers so long as they have the cash, a practice one former developer who worked with Trump calls “willful obliviousness.”

Mobsters have used Trump’s apartments and casinos to launder “untold millions in dirty money,” according to Unger, while one mobster ran a global sports betting ring using Unit 63A at Trump Tower, a condo directly below one owned by Trump, and all of the apartments on the 51st floor.

Unit 63A also served as the headquarters for a sophisticated money-laundering scheme that authorities say moved $100 million out of the former Soviet Union through shell companies in Cyprus and into investments in the U.S. The scheme operated under the protection of Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov, whom the FBI says is a top aide of Semion Mogilevhich, whom it considers the “boss of bosses” of the Russia mafia and brillian creator of innumerable money-laundering schemes.

Tokhtakhounov, who infamously tried to fix the ice-skating competition at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, fled the U.S. after the sports betting ring was busted, but was a Trump guest of honor at a Moscow beauty pageant seven months later although he was a U.S. fugitive.

David Bogatin, a retired Red Army pilot with no visible signs of income, plunked down $6 million for five Trump Tower units in 1984. Trump attended his closing.

Bogatin turned out to be a leading figure in the Russian mob in New York while his brother ran a $150 million stock scam for Mogilevhich. Bogatin pleaded guilty in 1987 to taking part in a massive gasoline bootlegging scheme with Russian mobsters and fled the country. The government seized his five Trump Tower condos.

In 2001, when Trump opened Trump World Tower, then the tallest residential building in the city, on First Avenue in Manhattan, a third of the units on the tower’s priciest floors were bought by individual buyers or limited liability companies with connections to the former Soviet Union.

Among the initial buyers were Kellyanne Conway, a future Trump campaign manager and administration adviser, and Eduard Nektalov, a diamond dealer from Uzbekistan who lived directly below Conway and was being investigated by the Treaury Department for Russian mob-connected money laundering. When word got out that Nektalov was cooperating with the feds, he was assassinated in broad daylight on Sixth Avenue.

Yet for all the bad behavior that Trump’s shady associates have exhibited, Trump has never been charged with any crime, although there are increasing calls in Congress to investigate how he built his business empire.

and Felix Sater, who were partners in Bayrock Group — and crime

The most striking aspect of Trump’s Russia connections is how many people the man who is now president has sought out and formed long-term business relationships with who have dedicated their lives to sleaze and crime. In this regard, Felix Henry Sater is at the top of the list.

Sater is a Russian émigré. His father, Mikhael Sheferovsky (aka Michael Sater) was a boss in the crime syndicate run by Mogilevich.

Son Felix has extensive mob ties of his own, and while trying to make it as a stockbroker, ended up doing prison time for stabbing a Wall Street competitor in the face with the broken stem of a margarita glass during a bar fight. The man needed 110 stitches to close the wound.

Sater became a federal informant to avoid a 20-year mandatory scheme to defraud elderly victims of $40 million, most of them Holocaust survivors, and stayed out of prison in more recent years ostensibly because of what he has done for the U.S. as opposed to against it. This includes ratting out mobsters for the FBI in two big Mafia cases, a failed effort to buy stinger missiles in Afghanistan on the black market for the CIA, as well as supposedly trying to obtain Osama bin Laden’s cell phone number.

More recently, Sater tried his hand at “diplomacy” on Trump’s behalf to give Russia a fig leaf for its invasion and illegal annexation of the Crimea region of Ukraine.

The other players in the scheme were Michael Cohen, who is Trump’s personal lawyer (as opposed to his growing roster of criminal lawyers), and Andrii Artemenko, a wealthy oligarch and member of the Ukraine Parliament. Artemenko told Sater and Cohen that Putin’s senior aides had personally blessed the plan, which Cohen delivered to none other than then-National Security Adviser Michael Flynn at the White House shortly before Flynn’s unceremonious ouster because of his own Russia connections.

The biggest Trump-Sater connection is Bayrock Group, an international real estate and investment company in which Sater was the chief operating officer. Bayrock was a co-developer of Trump SoHo, a swank 46-story condo-hotel where SoHo meets Tribeca and the West Village in Lower Manhattan, that Trump lent his name to in return for 18 percent of the profits without putting up any of his own money.

Trump SoHo was foreclosed on and resold after Trump and fellow promoters were sued by buyers who accused them of fraudulently inflating sales figures to encourage them to buy units. Trump has run the building for the new owners and he and daughter Ivanka still are listed as managers of the property.

Other Bayrock deals didn’t work out so well. International projects in Russia and Poland flopped and a Trump Tower being built in Fort Lauderdale ran out of money before it was completed.

Tevfik Ariv was a partner with Trump and Sater in Trump Soho and would seem to be an immigrant success story.

Ariv worked as a Soviet trade and commerce official for 17 years before moving to New York and founding Bayrock. Practically overnight, he became a hugely successful developer and after meeting Trump in 2002 moved Bayrock’s offices to Trump Tower.

It turned out Bayrock was financed by a notoriously corrupt group of Russian oligarchs know as The Trio who used it to develop Trump properties and then used the properties to launder money. Then in 2010, Arif was arrested by Turkish prosecutors and charged with running a prostitution ring after he was found aboard a boat chartered by one of The Trio with nine young women.

Joining Bayrock in developing Trump SoHo was the Sapir Organization.

Tamir Sapir, who introduced Trump to Arif, emigrated from the Soviet Union in the 1970s. He started out driving a cab in New York City and ended up a billionaire living in Trump Tower. His partner in the high-tech electronics firm that made him rich was a member of the Russian mob.

Trump has described Sapir as a “great friend,” bought 200 televisions from the electronics firm, and hosted the 2007 wedding of Sapir’s daughter at Mar-a-Lago.

for a luxury apartment tower on the Black Sea coast

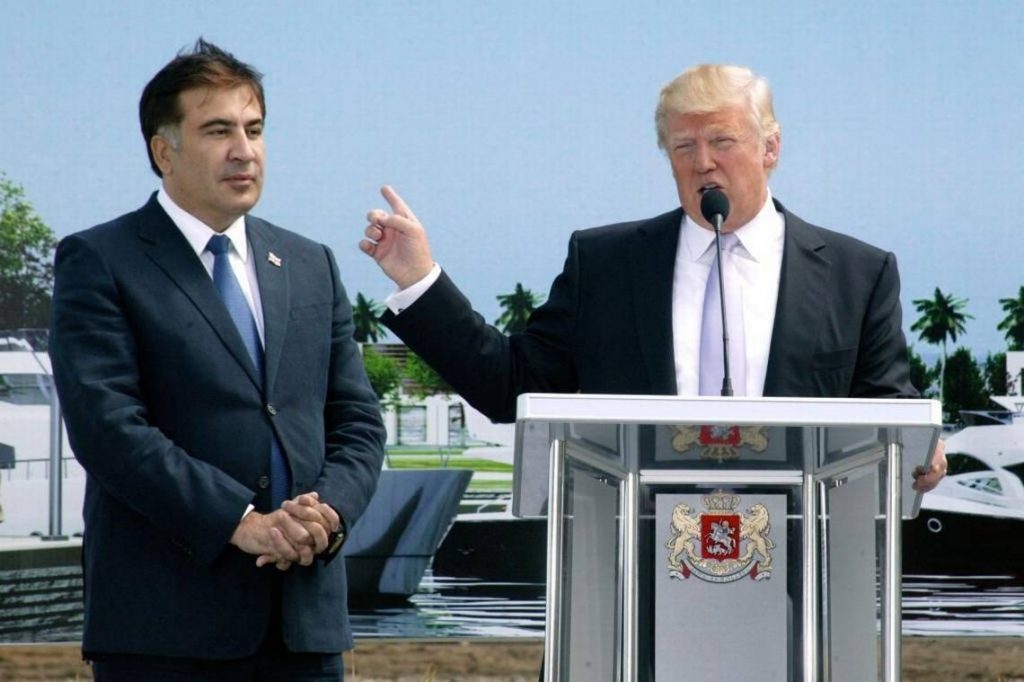

Only weeks before his inauguration, Trump allied himself with a company in the former Soviet republic of Georgia that planned to build a 47-story luxury apartment tower in the resort of Batumi.

“The whole aesthetic of Trump goes very well with Central Asia,” Asia expert Alexander Cooley of Columbia University told McClatchy News Service reporters Kevin Hall and Ben Wieder. “The emphasis on ‘the personal is political,’ the use of personal connections . . . this kind of murky world of transnational relations in real estate, relatively unregulated and unmonitored.”

Hall and Wieder found that Trump’s businesses are spread well beyond U.S. borders. At least 159 of the 565 companies Trump listed in his most recent financial disclosure report were tied to businesses abroad.

The deal for the Batumi tower fell through in January, as had an earlier 2012 deal, but had it not the edifice would have borne Trump’s name and he would have received royalties through Silk Road Group, a trading and transportation company that has deals with companies in Russia and Iran, both targets of U.S. sanctions.

Trump revealed none of this in his financial disclosure statements, nor was it mentioned that Silk Road is a strategic fuel supplier to U.S. and NATO troops in Afghanistan and had partnered with two Kazakh oligarchs and their kin who are accused of stealing billions of dollars of Kazakh money and laundering it through luxury U.S. real estate, including Trump SoHo and other Trump-branded condo towers.

Ukraine has recently asked Switzerland to extradite Ilyas Khrapunov, son of former Kazakh Energy Minister Viktor Khrapunov, for alleged computer hacking. Switzerland is where Ilyas and his wife secured unusual diplomatic posts representing the Central African Republic, which has enabled them to travel more freely.

Meanwhile, federal lawsuits have been filed by the city of Almaty against Ilyas and Viktor, who is a former mayor of Almaty, Kazakhistan’s largest city. Both Khrapunovs and Ilyas’s father-in-law, Mukhtar Ablyazov, face numerous criminal charges in Kazakhistan. Ablyazov was owner of BTA Bank until it was seized by regulators in 2009 after $10 billion went missing from the bank.

Among the dozens of companies lawyers for Almaty say the Khrapunovs created to launder money were three limited liability companies called Soho 3310, Soho 3311 and Soho 3203, all corresponding with units they bought at Trump SoHo.

(There already is evidence that a consequence of Trump’s Russia connections is that Russian money laundering cases are being treated more leniently. In May, the Justice Department abruptly settled a case against Prevezon Holdings, which was accused of laundering dirty money through Manhattan real estate, for a mere $6 million. One of Prevezon’s lawyers was Natalia Veselnitskaya, who, accompanied by a Russian spy, infamously met with Donald Trump Jr. and the Trump campaign brain trust in Trump Tower in June 2016.)

Court documents filed in conjunction with the Khrapunov extradition request list Sater as having been involved in some of the Khrapunov’s transactions at the same time he was doing deals with Trump.

But while Sater considers himself a close personal adviser to Trump, likes to say that he’s playing his “Trump card” and his business cards list him as “senior adviser to Donald Trump” with an office at Trump Tower, Trump himself has repeatedly said he barely remembers Sater.

In sworn testimony in 2013, Trump said he wouldn’t recognize Sater if they were sitting in the same room. Kind of like not recognizing his many Russia connections.