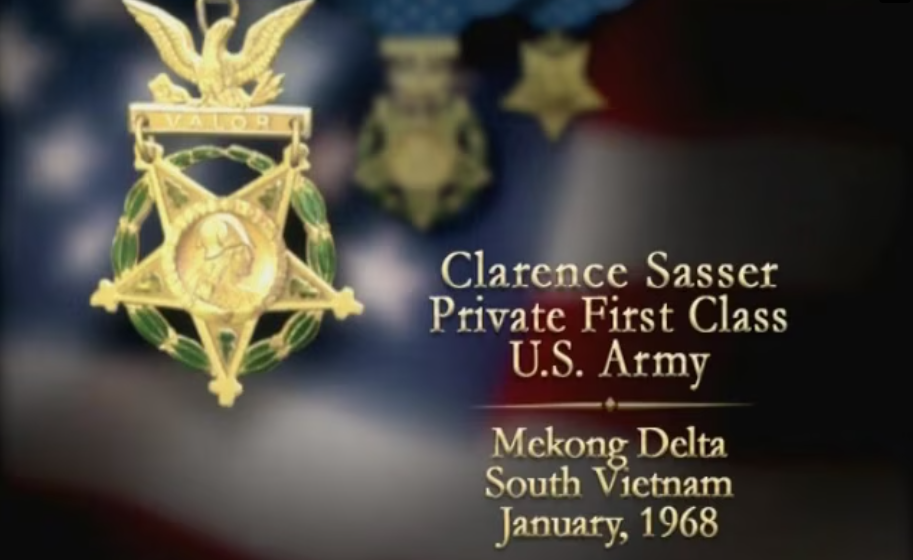

This week, I am both proud and sad to write about Spc. 5th Class* Clarence E. Sasser, Medal of Honor recipient.

Proud, because Sasser attended my alma mater, Texas A&M University.

Sad, because he passed away just over a week ago.

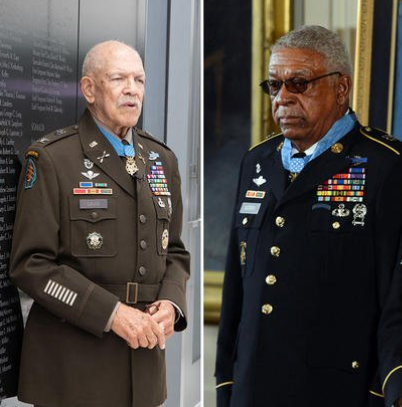

With the passing of Sasser, there are only 61 recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor alive today. Two of them Black.

Shown below, are the two remaining living Black Medal of Honor recipients.

Sasser is one of eight Aggies who have been awarded our nation’s highest military decoration for valor in combat. Seven for their heroism during World War II, one – Sasser – for valor in the Vietnam War. He is one of 23 African American servicemembers to receive the Medal of Honor for actions above and beyond the call of duty in the Vietnam War.

Clarence E, Sasser, a Brazoria County, Texas, native, passed away May 13, 2024, at Sugarland, Texas. He was 76, the last Aggie living recipient of the Medal of honor prior to his death.

Sasser was born on Sept. 12, 1947, in Chenango, Texas, a small community south of Houston.

He grew up on a farm with his mother, stepfather, a brother, sister and four stepsiblings.

In the fall of 1965, after graduating near the top of his class from one of the last segregated classes at Marshall High School, Sasser briefly attended the University of Houston, studying chemistry, but was forced to take a job to pay for classes, losing his student deferment.

In June 1967, at the height of the Vietnam War, he enlisted in the Army and was assigned to Ft. Sam Houston where he trained as a medical aidman.

Three months later he was on his way to Vietnam, assigned as a medic with the 3rd Battalion, 60th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division. He had just turned 20.

His tour of duty would last less than 60 days.

In the DoD January 17, 2022, “Medal of Honor Monday” feature, Katie Lange writes:

On Jan. 10, 1968, then-Private 1st Class Sasser was with Company A on a reconnaissance mission to the Mekong River Delta to investigate reports of enemy activity. That morning, as about a dozen company helicopters were landing, they suddenly started taking heavy fire from three sides of the landing zone. A well-entrenched enemy using rockets, machine guns and small arms managed to take down 30 American fighters in the first few minutes of the attack.

“I got grazed getting off the helicopter, in the leg,” Sasser said during a Library of Congress Veterans History Project interview in 2001. “[There was] fire all around us. With the helicopter down, there wasn’t any choice. We had to go in.”

Through a hail of gunfire, Sasser ran across an open rice paddy to help his injured comrades. As he helped one soldier to safety, he was wounded again, this time in the left shoulder by fragments of an exploding rocket.

:

Sasser ignored his injuries and ran through a barrage of rocket and automatic weapons fire to help two more men before moving on to search for others who were wounded. After suffering two more injuries that immobilized his legs, Sasser dragged himself through the mud to continue his work.

:

After crawling roughly 100 meters, Sasser treated another soldier before encouraging more men to crawl 200 meters to relative safety. Once there, he treated them over the course of the night. Sasser said if it wasn’t for Air Force close air support dropping bombs to keep the enemy off them, they likely all would have died.“We laid there that night. All you could hear was guys moaning, calling for their mama,” he remembered. “Listening to them beg all night … It was the toughest thing I’ve ever done.”

Sasser said evacuation helicopters finally came for them around 4 a.m. or 5 a.m. the next day.

“It was a relief. We were out of there, and I was still alive. I was hurting, but I wasn’t in mortal danger,” Sasser said of his feelings at that moment. “I had made it.”

Sasser was treated at a hospital before being evacuated to Japan for further recovery. During his rehabilitation, he helped out at the hospital’s dispensary, and a doctor he’d befriended was able to get him reassigned there instead of returning to Vietnam.

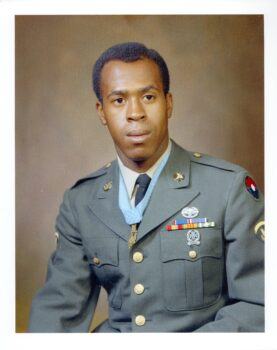

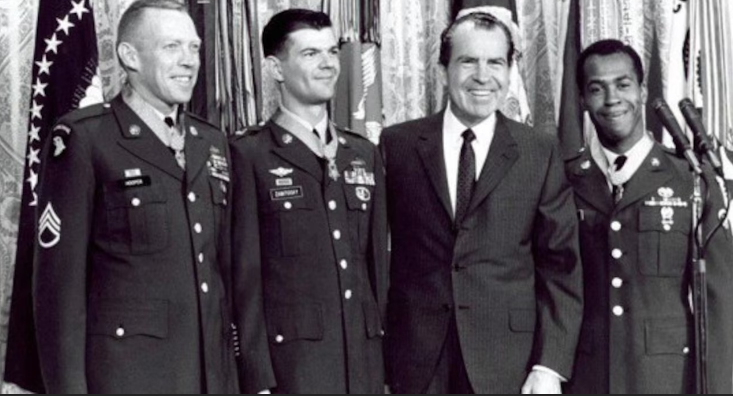

Clarence Eugene Sasser received the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon on March 7, 1969, during a White House ceremony (below).

Sasser was subsequently offered a scholarship to Texas A&M by university president and fellow Army veteran James Earl Rudder. Sasser elected to continue studies in chemistry, enrolling as a chemistry major in August of 1969.

After marrying Ethel Morant, Sasser went to work for a Houston-area oil refinery where he worked for more than five years before being employed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs where he retired.

Many additional honors have been bestowed upon Sasser:

He is a Distinguished Alumnus of Texas A&M and holds an honorary Doctorate of Letters from the university, as well as a Core Values Coin Award from The Association of Former Students.

His name is enshrined in the Memorial Student Center’s Medal of Honor Hall of Honor on the Texas A&M campus alongside the other seven other Aggie Medal of Honor recipients.

In his home county, a statue of him stands in front of the Brazoria County Courthouse and his portrait hangs in the Texas State Capitol.

In a statement on Sasser’s passing, Texas A&M President Gen. (Ret.) Mark A. Welsh III. said in part, “Aggies will celebrate him forever. Not just because he earned the Congressional Medal of Honor, but because he represented it so proudly with a life of honor, integrity and service. Rest in peace, Soldier … and thank you.”

Texas A&M System Chancellor John Sharp added, “Clarence brought honor to his country, his family and to Texas A&M. We are so proud to count him as one of our sons of Texas A&M.”

In 2013, during his Hall of Honor recognition ceremony, Sasser said, “I’m an Aggie at heart — always have been and always will be.”

Below is a video on Clarence Sasser by the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

* Note: Sasser was a Private 1st Class at the time of his Medal of Honor actions. His highest rank was Spc. 5th Class.