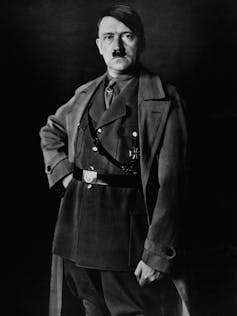

History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Michael Scott Bryant, Bryant University

Late in 1938, Nazis across Germany attacked Jews and their homes, businesses and places of worship and arrested about 30,000 Jewish men. The attacks became known as Kristallnacht – the “Night of Broken Glass” – for the streets littered with broken glass from the vandalism.

But the pogrom of Nov. 9-10, 1938, went beyond the broken glass of Jewish-owned shops on the streets of German cities and has rightly been called a major turning point in the history of the Holocaust.

As a scholar specializing in the impact of the Holocaust on the law, human rights, German criminal law and international humanitarian law, I believe it’s important to see Kristallnacht as the logical culmination of Hitler’s malevolent intentions going back many years before 1938. Seeing it that way allows us to view the two different kinds of antisemitism in Hitler’s thinking, one involving emotions and the other involving the law and reason.

Indeed, the November pogrom and its aftermath foreshadowed the mass shooting squads and death camps of the early 1940s – institutions that were likewise products of a willful malice toward Jews.

Hitler’s two kinds of antisemitism

From early in his political career, Hitler’s thinking about Jews vacillated between attacking them violently or through patient, step-by-step legal measures. He even had terms to describe these two approaches.

In a September 1919 letter, Hitler recommended that the status and treatment of Jews could best be addressed through the “antisemitism of reason” rather than the “antisemitism of emotion.”

Hitler wrote that emotional antisemitism, which was expressed in the episodic violence of pogroms, would not have lasting effect.

In contrast, he wrote, the “antisemitism of reason” would work through law to achieve an enduring solution to what he called the “Jewish problem.” The “final objective” of rational antisemitism, according to Hitler, “must be the total removal of all Jews from our midst.”

Much of Hitler’s career reflected his adherence to this antisemitism of reason.

This ideological conviction, however, clashed with the antisemitism of emotion also in Hitler’s thinking. In interviews with journalists in the early 1920s, Hitler sometimes said he would attack and eradicate German Jews when he came to power.

Corbis via Getty Images

In one interview in 1920, he vowed to hold public hangings of Jews throughout Germany. In another interview, he admitted the best solution was to “murder” the Jews “in the night.”

These violent, pogrom-style musings conflicted with Hitler’s legal approach.

This tension would continue through the 1930s as the Nazis passed laws to remove Jews from German public life. Even as Jews were banned from the civil service, legal profession and medicine, wildcat attacks on them by the SA, the paramilitary arm of the Nazi party, were common.

Less radical Nazi leaders worried that such attacks would undermine Germany’s foreign relations. To allay these concerns, Hitler forbade anti-Jewish violence that could be inopportune for his government. Thus, attacks on Jews were suspended before and during the 1936 Olympics as well as during the Munich crisis, in which Great Britain and France agreed to allow Germany to annex the Sudetenland in western Czechoslovakia.

In both cases, pogrom violence against Jews resumed after the regime had achieved its goals.

Hitler sets pogrom in motion

On Nov. 7, 1938, a German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath, was mortally wounded in Paris by a distraught Jewish shooter, Herschel Grynszpan.

The nationwide pogrom that ensued was novel only in its intensity and scale. In fact, violence against Jews had already rippled across southern and central Germany during the summer of 1938. At this time, the synagogues in Nuremberg and Munich were both destroyed.

History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A Security Service report in October 1938 described this earlier violence as having “a semi-pogrom character.”

When the pogrom of Nov. 9-10, 1938, erupted, it was anything but a bolt out of the blue.

Like the destruction on his order of the Munich synagogue in August 1938, Hitler set the November pogrom in motion. He then distanced himself from the event to avoid being seen as the instigator, blaming the violence on the “people’s rage.”

Clearly, however, the pogrom took place on Hitler’s orders.

The November pogrom in Holocaust history

This is one of the most important truths of the November pogrom: Hitler finally resolved his internal conflicts over the most effective way to rid Jews from Germany.

In the November pogrom, the antisemitisms of reason and emotion, of dispassionate law and thuggish violence, were brought into alignment for Hitler. Pogrom-style violence would be channeled not through the paramilitary SA but through government channels controlled by the Nazis.

In short, extreme violence against Jews would no longer be left to the Nazi brownshirts. Rather, it would be wielded by the German government.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In a hastily convened meeting of Nazi leaders on Nov. 12, 1938, the participants recommitted themselves to the antisemitism of reason. A raft of anti-Jewish laws would soon be passed.

In late January 1939, a Central Office for Jewish Emigration was set up under Reinhard Heydrich, second in command within the SS to Heinrich Himmler. The role of his new office was to force Jewish emigration from Germany through terror and intimidation.

With the November pogrom, Hitler overcame the split between the two types of antisemitism that had pervaded his thinking since 1919.

The “rational” antisemitism of laws, decrees and orders would be combined with the destructive violence of emotional antisemitism. The fate of the Jews would henceforth be entrusted to the cold racial vanguard of the Nazi movement, the SS.

By 1941, their actions would surpass the comparatively modest mayhem of the Nazi paramilitary soldiers as Nazi violence moved from fists and clubs to the “Final Solution” of genocide.![]()

Michael Scott Bryant, Professor of History and Legal Studies, Bryant University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.