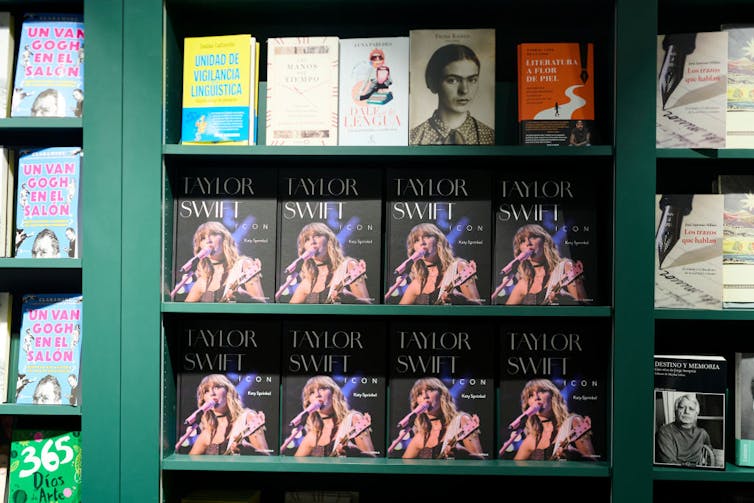

Ashok Kumar/TAS24/Getty Images for TAS Rights Management

Jessica Flanigan, University of Richmond

Taylor Swift isn’t just a billionaire songwriter and performer. She’s also a philosopher.

As a Swiftie and a philosopher, I’ve found that this claim surprises Swifties and philosophers alike. But once her fans learn a bit more about philosophy – and philosophers learn a bit more about Swift’s work – both groups can appreciate her songwriting in new ways.

Looking in the mirror

When one of the greatest philosophers, Socrates, famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living,” he was arguing that people cannot even know whether they are living a meaningful life unless they subject their choices and their values to scrutiny.

Like other great writers, Swift’s songwriting consistently involves just the kind of introspective scrutiny about choices and values that Socrates had in mind. Several songs address the value of self-understanding, even when it’s difficult.

Amid a breakup, the narrator in “Happiness” sings, “Honey, when I’m above the trees I see this for what it is.” Yet she describes how it can be hard to maintain an objective perspective on a relationship while also navigating the end of it. “And in the disbelief I can’t face reinvention / I haven’t met the new me yet,” she sings. Her partner is looking for “the green light of forgiveness,” when she tells them that “You haven’t met the new me yet / And I think she’ll give you that.”

The Swift-like narrator in “Anti-hero” makes a similar point about the challenges of self-awareness. “I’ll stare directly at the sun, but never in the mirror,” she sings, referencing how it’s often easier to identify truths about the external world than to face facts about oneself, and that her tendency toward self-deception limits her ability to become wiser with age.

Everyone inherits a set of beliefs and assumptions from their parents, peers and culture, which can inhibit our ability to truly understand others and ourselves.

In Swift’s “Daylight,” she describes how she once viewed relationships as “black and white” or “burning red.” Letting go of those old, reductive narratives enabled her to see her relationships – and herself – more clearly. She’s emerged from what she describes as a “twenty-year dark night” to see the more complicated, liberating truth: daylight.

Argue toward truth

Socrates showed that the best way to scrutinize one’s choices and values is through sustained, sometimes argumentative, conversation with others. To a nonphilosopher, philosophy often looks like devil’s advocacy or trolling – arguing just for the sake of it. But to philosophers, disagreeableness is a virtue that helps counteract reflexive dogmatism and conformity.

Swift, too, is argumentative in her songwriting, often making a moral argument to an imagined listener – frequently, a romantic partner. In other lyrics, Swift rebuts unfair critics and record executives.

Recently, her lyrics have begun to address more public issues, like the promise and futility of politics. At first glance, “Miss Americana & The Heartbreak Prince,” released in 2019, is a coming-of-age song about teenage relationship drama. However, Swift is also describing her own political awakening and disillusionment when she writes, “My team is losing, battered and bruising.” Lyrics like, “American stories burning before me” and “You play stupid games, you win stupid prizes” further reinforce a parable about political despair.

Graham Denholm/TAS24/Getty Images for TAS Rights Management

At the same time, other songs develop arguments for the promise of advocating for political change. In “Only The Young” she addresses someone who sees that “The game was rigged,” reminding them “They aren’t gonna change this / We gotta do it ourselves … Only the young can run.”

Swift’s nonpolitical songwriting also has implications for long-standing ethical debates. In “Gorgias,” a dialogue written by Socrates’ student Plato, the philosopher asks whether it is better to suffer injustice than to commit it – a theme that appears in several Swift songs.

Socrates argued it is better to suffer injustice, because committing injustice is an affront to one’s own dignity and integrity. In her 2022 song “Karma,” Swift seemingly agrees: “Don’t you know that cash ain’t the only price?” of immorality, before she warns her listener that karma’s “coming back around.”

True ? and false

For philosophers, every aspect of the human experience is fair game for further analysis. As the 20th century American philosopher Wilfrid Sellars wrote, the purpose of philosophy should be “to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.”

By holding people’s beliefs to logical standards of consistency and coherence, philosophical analysis reveals contradictions in an effort to discover what’s really true.

Swift’s songwriting addresses some of the trickiest paradoxes, such as whether there is even such a thing as a true, authentic self.

Borja B. Hojas/Getty Images

Tackling the question in “Mirrorball,” she seems to endorse the view that one’s sense of self is largely strategic, socially constructed to fit the situation. “I’m a mirrorball, I’ll show you every version of yourself,” she sings before stating, “I can change everything about me to fit in” and “I’ve never been a natural. All I do is try, try, try.”

Similarly, in “Mastermind,” Swift describes calculatedly trying to win someone’s affection when she sings, “I swear I’m only cryptic and Machiavellian ‘cause I care.” In both songs, Swift points out how authentic displays of vulnerability can also be a form of strategic speech, prompting the listener to wonder whether genuine authenticity is possible.

Another tricky paradox in philosophy involves the idea of supererogation, which refers to acts that are morally good but not morally required. This idea also allows that acts can be “suberogatory,” meaning that they are morally bad but nevertheless permissible.

Songs like “Champagne Problems” and “Would’ve Could’ve Should’ve” explore this paradoxical space, describing cases where someone made a morally criticizable choice that they were nevertheless entirely within their rights to make.

Relatedly, Swift is also interested in paradoxes of moral psychology. Songs like “This Is Me Trying,” “Illicit Affairs” and “False God” reflect on the philosophical concept of akrasia: cases where people seemingly know they shouldn’t do something but do it anyway.

A lot of the philosophical literature about akrasia asks whether it’s even possible: If someone believes their decision is wrong or bad for them, why would they do it? But through her lyrics, Swift sketches psychologically realistic vignettes that suggest genuine akrasia is at least possible and probably happening all the time – from sabotaging a loving relationship to pursuing one that “we were crazy to think … could work.”

Philosophy uses the conventions of logic and poetry to help people see the world more clearly. A successful philosophical conversation will involve making rational appeals – logic – that are also emotionally resonant – poetry.

But academic philosophers cannot claim to be the only people who deploy logic and poetry to advance understanding of the human condition, the world around us and the nature of justice. Songwriters like Taylor Swift can be philosophers too.![]()

Jessica Flanigan, Professor of Leadership Studies and Philosophy, Politics, Economics and Law, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.