Baruska/Pixabay, CC BY

Bérengère Stassin, Université de Lorraine

In France, the #MeToo movement has a livelier name: #BalanceTonPorc, or “Name and Shame Your Pig.” It inspired hundreds of women to denounce sexual harassment on the streets and in the boardroom.

The latest workplace harassment scandal, exposed online in mid-February, involved France’s so-called “LOL League” – an anonymous boys club in the media industry – that in 2010 began bullying female colleagues online.

Prominent news editors, including the managing editor of the French edition of Slate and of the venerable news daily Libération, had targeted female colleagues on Twitter and on Facebook, mocking them on their looks and ethnic origins or making sexist and racist slurs.

Many of these men had since climbed up in hierarchy in the news business, and, as #MeToo unfolded in 2017 and 2018, claimed that they were feminists.

France’s everyday sexism

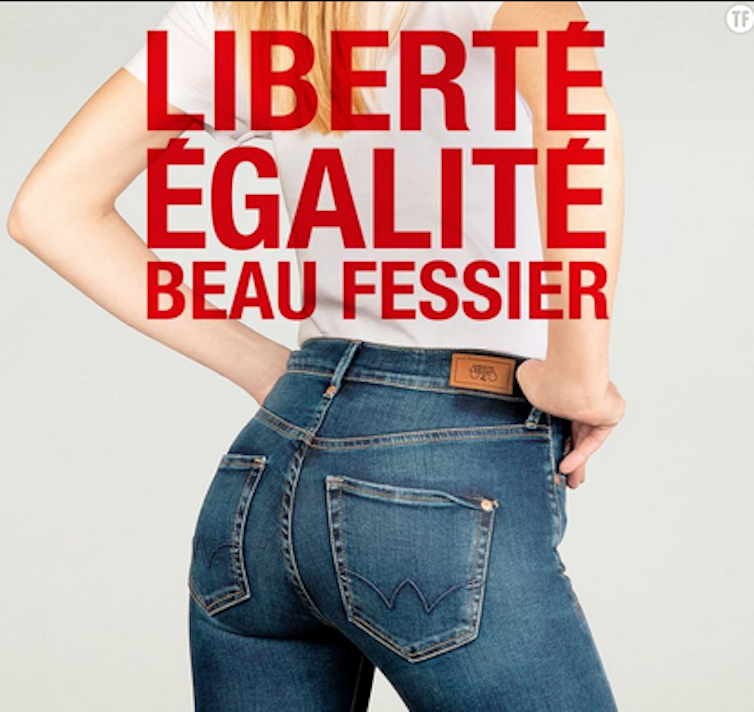

Sexism is an everyday occurrence in France, where clothing advertisements still use sex to sell products and men comment on women’s looks at the office and on the streets. Lewd comments are often defended as “just flirting.”

Flirtation was the argument some prominent French women – including actor Catherine Deneuve – have used to denounce #MeToo. In an open letter published in January 2018, 100 women denounced #MeToo as a puritan witch hunt, driven by a hatred of men, and claimed that French culture was simply different, more sexually expressive, than American culture.

Feminists across France rushed to defend #MeToo’s goals of exposing workplace misogyny and holding sexual harassers accountable. By summer 2018, thanks to their efforts, France passed a law criminalizing street harassment.

But the French backlash against #MeToo demonstrated a certain confusion in the country between what constitutes sexual freedom and what constitutes abuse.

In France, studies show, the tendency to pass off sexual harassment as harmless flirtation starts as early as primary school.

Sexual violence at school

Children do not always understand the difference between an intimate touch that is a consensual act of sexual discovery and a nonconsensual, inappropriate touch. And violence and harassment that take other forms – insults, mockery and rumors – are particularly hard for children to identify, and for adults to detect.

Both boys and girls may be subjected to sexism or sexual violence in the guise of a joke or of a game.

Recently, students in a school near Paris were all playing a game they’d learned on the social network Snapchat. It consisted of touching the other children’s private parts to earn “points.” During “Ass Day,” as the students called it, boys and girls allowed each other to touch or squeeze their genitals.

Not participating in this “game” was not really an option.

One female student told a school guard she did not consent to being touched. He looked the other way, and the groping continued. Even after school, the girl was trailed by boys trying to touch her on her way home.

She informed her parents, who went public with the story.

Cyberbullying

Other common coerced sexual encounters between students include forced kisses and voyeurism, especially spying on the boys’ or girls’ bathroom.

Smartphones and social networks put the tools of voyeurism in kids’ pockets.

Online variations of the bathroom peeping Tom include upskirting – when kids snap pictures up a girl’s skirt – and creepshotting, or taking a picture of a woman’s cleavage without her knowledge.

“Revenge porn” – when angry friends, school bullies or ex-partners post sexually explicit photos of a person without their content – is another danger children face on social networks.

In January 2018, about 50 high school girls in the eastern French region of Strasbourg discovered nude pictures of themselves – previously shared only with friends or boyfriends – published on Snapchat and Facebook groups linked to the school.

Boys are not the only ones to ridicule girls for their sexuality, a form of harassment known as slut shaming. In a bid to earn male approval and popularity, girls, too, post revenge porn and circulate upskirts at the expense of their female classmates.

Stereotypes create violence

Tension and aggressive behavior among teens is attributable to various factors in their development: puberty, identity building, peer group influence, seduction games.

But gender stereotypes are at the heart of this problem, too.

Stereotypes about how men and women should behave are conveyed by the media, at home and in the classroom. In France, teachers’ own internalized sexism may unintentionally lead them to enforce social norms about “flirtation” and the stereotypical roles of boys and girls.

This hurts boys, too. In France, where men are expected to display their sexual dominance, boys considered insufficiently “manly” can become victims of bullying and sexual violence.

“The socialization of boys draws two distinct groups,” says the French educator Eric Debarbieux. “Those who manage to show their strength, to be the strongest, the most virile; and others who risk being downgraded to the category of sub-human, or ‘fags.’”

Better sex education

Schools in France mostly address gender-based behavior and sexual violence during sex education classes.

The national sex ed curriculum, in place since 1973, is the now the subject of debate in the country.

Teachers discuss public health issues, relationships between girls and boys, the culture of equality, sexual violence, pornography and gender and homophobic prejudices.

Efforts since #MeToo to make French sex education more progressive – starting it at a younger age, for example, or to teach French elementary school children more about gender, sex and identity – have proven controversial. Last September, the French government found itself debunking accusations that it wanted to teach toddlers how to masturbate.

But if French schools contribute to national confusion about the difference between flirting and harassment, schools need to do more to develop students’ ability to think critically about gender roles as they are conveyed by the media, film, television and advertising.

Critically, younger children must be taught about consent, which will help them distinguish between seduction and aggression. France’s anti-#MeToo women wanted to protect the “freedom to bother,” which they say is necessary to give women the “freedom to say ‘no.’”

But children need to know, too, that they have the right to not be bothered.![]()

Bérengère Stassin, Maître de conférences en sciences de l’information et de la communication, membre du CREM, Université de Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.