More than three years before the Allies launched the single largest, most epic amphibious invasion in the history of mankind — the Normandy Invasion — the mission was already a twinkle in British eyes.

In March 1942, on the BBC evening news, an urgent call went out to the British people on behalf of the Royal Navy. It was asking Britons to send to the government any photos they had taken on the French coast, no matter how boring, trivial or mundane.

You see, unknown to the public, the Inter Services Topographical Department (ISTD) was assembling a detailed picture of the entire French coast and the Low Countries.

Why? Because “to plan an invasion, the navy had to render a depiction of the country from wave height, from the prow of an incoming landing craft…The navy had to know what the harbor and beaches looked like, the gradient of each sloping dune…”

The British people responded immediately, sending the government “some thirty thousand envelopes, including ten million vacation snaps.”

The ISTD was able to build “a photo mosaic, a montage of family memories, and stitched the panorama together for a colossal topographical quilt [that became] the platform for a battle plan of the Allied invasion of Europe.”

But even before this, while America was still on the sidelines, Winston Churchill foresaw the day when England, hopefully with the help of existing and future allies, would launch an attack on the Nazis on the Continent.

For the invasion and follow-on campaign to be successful, it was essential to gather crucial intelligence, deceive, soften the occupying force, cripple its infrastructure through espionage, deception, sabotage, targeted raids. In other words, through clandestine warfare, covert operations.

To this end, Churchill created a new, secret agency “for insurgency,” a professional fifth column. It was called the Special Operations Executive (SOE), or “the Firm,” whose agents were trained in everything from sabotage and demolition to sharpshooting. It would wage “…the dirtiest war, beyond the rules of engagement—warfare by every available means, including murder, kidnappings, demolitions, ransoms, and torture.”

SOE would need men, lots of them, on the ground in Europe, especially in France.

There was only one problem: With so many men already involved in the war effort, Britain was running out of men.

A young British Captain, Selwyn Jepson, was able to convince Winston Churchill of the appropriateness, ethics and legality of the then-unprecedented use of women for such dangerous war roles, especially considering the fact that women would be exposed to the worst of Nazi cruelties and depravations, should they be captured.

And so, more than three dozen brave and daring women were recruited, trained and parachuted into France during full moons or surreptitiously landed by sea onto French shores in pitch black darkness.

Their “job”: To gather intelligence, establish and operate drop zones for weapons, explosives and agents (“parachutages“); destroy railways and railway tunnels; blow up power lines; ambush Nazis, plot prison breaks; run safe houses, extract downed Allied fliers, rotate agents to and from England. All towards one purpose; to pave the way for the D-Day invasion and the ensuing Allied advance into occupied Europe.

A job so dangerous that one of the items in their “survival kits” was the “L-Pill,” “…the very last pill anyone would ever take…coated in rubber, sewn into the lining of a sleeve…filled with cyanide. If swallowed, it was harmless. If bitten, it was fatal.”

A job so dangerous that, of the thirty-nine women who answered the call, half were caught and imprisoned and a third did not return home alive.

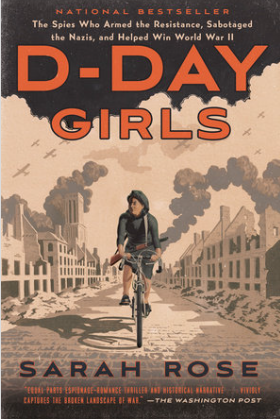

In her meticulously researched and documented (80 pages of notes and references), D-Day Girls, journalist and bestselling author Sarah Rose follows a handful of these heroines through thick and thin; trough success and failure; through romances, double agents and double-crossings; through capture, imprisonment, interrogation, torture, unspeakable atrocities, sickness and even death for some.

Rose published her book just before the 75th anniversary of D-Day. At the time she wrote:

Thirty-nine women of SOE went to war, and fourteen of them never came home. These women broke barriers, smashed taboos, and altered the course of history…They were sent undercover, so they never expected glory, and their story was classified for almost seventy years after the war. With the seventy-fifth anniversary of D-Day approaching this June, it is an honor to tell their story now.

Also praising her book at the time, Karen Abbott, author of Sin in the Second City, wrote, “…this is the Day book the world has been waiting for.”

D-Day Girls is not only a book that should be read on the 80th anniversary of that epic day, but a must-read book for any day of the year.