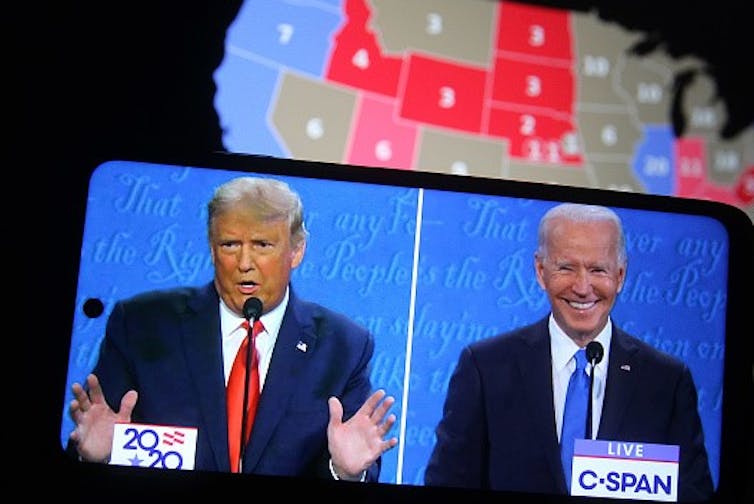

Pavlo Conchar/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Leo Gugerty, Clemson University

Some Americans are questioning whether elderly people like Joe Biden and Donald Trump are cognitively competent to be president amid reports of the candidates mixing up names while speaking and having trouble recalling details of past personal events.

I believe these reports are clearly concerning. However, it’s problematic to evaluate the candidates’ cognition based only on the critiques that have gained traction in the popular press.

I’m a cognitive psychologist who studies decision-making and causal reasoning. I argue that it’s just as important to assess candidates on the cognitive capacities that are actually required for performing a complex leadership job such as the presidency.

Research shows that these capacities mainly involve decision-making skills grounded in extensive job-related knowledge, and that the types of errors made by Biden and Trump do increase with age, but that doesn’t mean either candidate is unfit for office.

Intuitive vs. deliberative decision-making

There are two types of decision-making: intuitive and deliberative.

In intuitive decision-making, people quickly and easily recognize a complex situation and recall an effective solution from memory. For example, physicians’ knowledge of how diseases and symptoms are causally related allows them to quickly recognize a complex set of patient symptoms as matching a familiar disease stored in memory and then recall effective treatments.

A large body of research on fields from medicine to military leadership shows that it takes years – and often decades – of effortful deliberate practice in one’s field to build up the knowledge that allows effective intuitive decisions.

In contrast to the ease and speed of intuitive decisions, the most complex decisions – often the kinds that confront a president – require conscious deliberation and mental effort at each stage of the decision-making process. These are the hallmarks of deliberative decision-making.

For example, a deliberative approach to creating an immigration bill might start with causal reasoning to understand the multiple factors influencing the current border surge and the positive and negative effects of immigration. Next, generating possible bills may involve negotiating among multiple groups of decision-makers and stakeholders who have divergent values and objectives, such as reducing the number of undocumented immigrants but also treating them humanely. Finally, making a choice requires forecasting how proposed solutions will affect each objective, dealing with value trade-offs and often further negotiation.

Psychological scientists who study these topics agree that people need three key thinking dispositions – referred to as “ actively open-minded thinking” or “wise reasoning” – for effective deliberative decision-making:

-

Open-mindedness: Being open-minded means considering all of the choices and objectives relevant to a decision, even if they conflict with one’s own beliefs.

-

Calibrated confidence: This is the ability to express confidence in a given forecast or choice in terms of probabilities rather than as certainties. One should have high confidence only if evidence has been weighted based on its credibility and supportive evidence outweighs opposing evidence by a large margin.

-

Teamwork: This involves seeking alternative perspectives from within one’s own advisory team and from stakeholders with conflicting interests.

Presidents need to use both intuitive and deliberative decision-making. The ability to make smaller decisions effectively using intuitive decision-making frees up time to concentrate on larger ones. However, the decisions that make or break a president are exceedingly complex and highly consequential, such as how to handle climate change or international conflicts. Here is where deliberative decision-making is most needed.

Effective intuitive and deliberative decisions both rely on extensive job-related knowledge. Especially during deliberative decision-making, people use conceptual knowledge of the world that is consciously accessible, commonly referred to as semantic memory. Knowledge of concepts such as tariffs, Middle East history and diplomatic strategies allows presidents to quickly grasp new developments and understand their nuances. It also helps them fulfill an important job requirement: explaining their decisions to political opponents and the public.

What to make of forgetfulness and word mix-ups

Biden has been criticized for not recalling details of his personal past. This is an error in episodic memory, which is responsible for our ability to consciously recollect personal experiences.

Neurologists agree, however, that Biden’s episodic memory errors are within the range of normal healthy aging and that the details of one’s personal life are not especially relevant to a president’s job. That’s because episodic memory is distinct from the semantic memories and intuitive knowledge that are critical to good decision-making.

Mixing up names, as Biden and Trump occasionally do, is also unlikely to affect job performance. Rather, it simply involves a momentary error in retrieving information from semantic memory. When people make this common error, they usually still understand the concepts underlying the mixed up names, so the semantic knowledge that helps them deal with life and work is intact.

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

Making complex decisions as you age

Because all of us use a myriad of concepts to navigate the world every day, our semantic knowledge typically does not decrease with age, lasting at least until age 90. This knowledge is stored in posterior brain regions that deteriorate relatively slowly with age.

Research shows that, since intuitive decision-making is learned by extensive practice, older experts are able to maintain high performance in their field as long as they keep using and practicing their skills. As with semantic memory, experts’ intuitive decision-making is controlled by posterior brain regions that are less compromised by aging.

However, older experts must put in more practice than younger ones to maintain previous skill levels.

The thinking dispositions that are key to deliberative decision-making are influenced by early social learning, including education. Thus, they become habits, stable characteristics that capture how people typically make decisions.

Evidence is emerging that dispositions such as open-mindedness do not decline much and sometimes even increase with age. To investigate this, I looked at how well open-mindedness correlated with age, while controlling for education level, using data from 5,700 people in the 2016 British Election Study. A statistical analysis showed that individuals ages 26 to 88 had very similar levels of open-mindedness, while those with more education were more open-minded.

Applying this to the candidates

As for the 2024 presidential candidates, Biden has extensive knowledge and experience in politics from more than 44 years in political office and thoroughly investigates and discusses diverse viewpoints with his advisers before reaching a decision.

In contrast, Trump has considerably less experience in politics. He claims that he can make intuitive decisions in a field where he lacks knowledge by using “common sense” and still be more accurate than knowledgeable experts. This claim contradicts the research showing that extensive job-specific experience and knowledge is necessary for intuitive decisions to be consistently effective.

My overall interpretation from everything I’ve read about this is that both candidates show aspects of good and poor decision-making. However, I believe Biden regularly displays the deliberative dispositions that characterize good decision-making, while Trump does this less often.

So, if you’re trying to assess how or whether the candidates’ age should affect your vote, I believe you should mostly ignore the concerns about mixing up names and not recalling personal memories. Rather, ask yourself which candidate has the key cognitive capacities necessary to make complex decisions. That is, knowledge of political affairs as well as decision-making dispositions such as open-mindedness, calibrating confidence to evidence, and a willingness to have your thinking challenged by advisers and critics.

Science cannot make firm predictions about individuals. However, the research suggests that once a leader has developed these capacities, they typically do not decrease much even with advanced age, as long as they are actively used.![]()

Leo Gugerty, Professor Emeritus in Psychology, Clemson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.