Chesnot/Getty Images

Pamela S. Nadell, American University

Since buying Twitter, rebranded as X, billionaire Elon Musk, who calls himself a “free speech absolutist,” has welcomed hatemongers to the platform, including one who recently coined the trending hashtag #BanTheADL.

The ADL, the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, was founded in 1913 during the trial of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory manager wrongly convicted of murdering one of his young workers. After Georgia Gov. John Slaton commuted Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment, Frank was lynched. Since then, the ADL has aimed to fight antisemitism and secure “justice not only for Jews but for all people.”

Musk attacked the ADL on Sept. 4, 2023, saying that “Our US advertising revenue is still down 60%, primarily due to pressure on advertisers by @ADL.”

As #BanTheADL trended on X, users tweeted that it is “anti-Christian.” One said, “When you say #BanTheADL, what you really mean is #BanTheJews from power and organizing against white western civilization.”

The tweets may be new; as a scholar of Jewish history, I know the ideas they contain are not.

Religious antisemitism

The belief that Jews are “anti-Christian” comes from the Gospels, where Jews are blamed for the crucifixion of Jesus. As Christianity became the dominant faith in the Roman Empire in the late fourth century, Jews, condemned by the church for their treachery, faced discrimination. Beginning with restrictive legislation, it led eventually to locked ghetto walls and brutal attacks.

Immigrants to America carried ideas about Jewish enmity along with their rucksacks. In 1654, New Amsterdam Gov. Peter Stuyvesant tried to expel 23 Jews fleeing persecution who had just landed in the colony. He called them a “deceitful race – such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ.”

In October 2022, when white supremacists hung banners over Highway 405 in Los Angeles, some news sites blurred one. That particular banner pointed to the Gospel of John, where Jesus tells the Jews, “You are from your father the devil.”

And a few days after Musk blamed the ADL for ad revenue losses, a user of X posted a video of ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt and wrote, “Watch his demonic face recoil when he says the word Christian.”

Jews and money

The antisemites attacking the ADL dredged up old stereotypes falsely depicting the Jews as a people interested only in money, malevolently employing their wealth to undermine the political order.

A maliciously false tweet on Sept. 9, 2023, proved that #BanTheADL was not just about attacking one Jewish organization, which no one could accuse of being “the richest group in the world.” It expanded beyond the ADL and targeted all Jews: “The richest group in the world, who owns 99% of the media, controls the monetary system and started every war on Earth – is portrayed as the *victims* … under assault by ‘antisemitism.’”

Since Judas betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver in 33 C.E. – depicted in Matthew 26:14-15 – Christians have cast Jews as venally corrupted by money. Judas, the Greek version of Judah, refers to the tribe of ancient Israelites who became known as Jews. Shakespeare propelled that idea forward with the wicked moneylender Shylock in his 16th-century play “The Merchant of Venice.”

Shylock’s name has come to signify Jewish greed and villainy, a charge that spills over to other wealthy Jews. Mississippi Gov. Alexander Gallatin McNutt raged in 1841 about the power of the British Baron Rothschild, a member of the international Jewish banking family: “The blood of Judas and of Shylock flows in his veins.”

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of the Katz Family

Money buys power

After Musk’s targeting of the ADL, contemporary antisemites jumped to targeting the Hungarian Holocaust survivor and billionaire philanthropist George Soros, with a Sept. 7, 2023, post on X quoting Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban saying that Soros “has an ARMY at his service, MONEY, #NGO’s, Universities, research institutions and he OWNS half the bureaucrats in BRUSSELS!!”

Conspiracy theories about Jewish leaders using their money to acquire political power predated the notorious forgery, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” First published in an obscure newspaper in Russia in 1903, it was brought to America by a Russian émigré determined to restore the Romanov monarchy. It described an imagined meeting of Jewish elders who reported on their progress in fomenting revolutions to destroy western Christian civilization and seize control of the world.

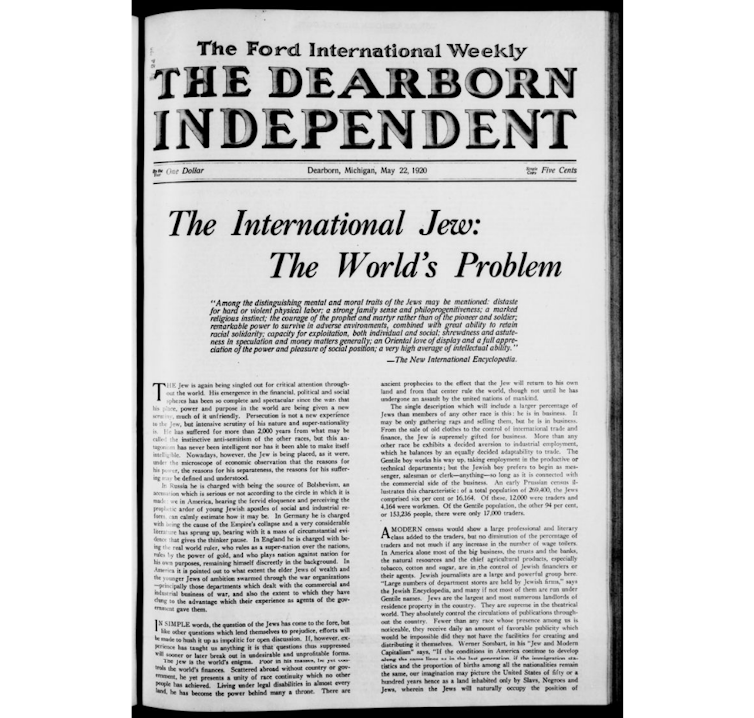

In the early 1920s, this version of antisemitism – claiming a world Jewish conspiracy – found a home in America thanks to the publication of “The International Jew – The World’s Foremost Problem.” A compilation of the articles that ran for 91 weeks in the newspaper Dearborn Independent, “The International Jew,” financed and published by Henry Ford, charged that Jews exercised outsize influence in America, that they controlled the world’s finances and that they were the “power behind many a throne.”

The Protocols’ antisemitic fantasies of Jewish leaders plotting to destroy Christianity and control the world also inspired Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” written in 1924 while he was in jail for trying to overthrow Germany’s government. There, referring to World War I, Hitler said if “during the War twelve or fifteen thousand of these Hebrew corrupters of the people had been held under poison gas … the sacrifice of millions at the front would not have been in vain.”

Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress

Victim blaming: Jews cause antisemitism

Elon Musk has tweeted that ADL’s aggression against antisemites posting on X makes them the “biggest generators of anti-Semitism on this platform.”

Blaming Jewish behavior for triggering antisemitism also has deep roots. The second-century Greek Bishop Father Melito of Sardis made it clear that the Jews had not only killed Jesus, they had stubbornly failed to recognize that he was God. Over the centuries, his words would be used to justify violence against the Jews.

During the Civil War, when Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant expelled Jews from his military district, called the Department of the Tennessee, which stretched from the southern tip of Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico, he charged that the punishment fit their crime: “The Jews, as a class, [were] violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department.”

In 1890, the editors of the New York Jewish newspaper the American Hebrew were so distressed by the prevalence of antisemitism that they asked more than 50 American leaders about antisemistism, collected in a volume entitled, “Prejudice against the Jews: Its Nature, Its Causes and Remedies. A Consensus of Opinion by non-Jews.” Rev. Morgan Dix, minister of Episcopal Trinity Church, made it clear in his response that, if only Jews would stop being so obstinate and convert to Christianity, antisemitic persecution would end.

In 1938, on the eve of the Holocaust, when Germany’s Jews were being targeted with antisemitic regulations but had not yet experienced the horror of the death camps, 65% of Americans told the polling firm Gallup that these victims were either “partly” or “entirely” responsible for the persecution they faced.

The hashtag #BanTheADL recycles variations on old antisemitic themes. X’s users write nothing new. What is new is the bigger megaphone X gives them.![]()

Pamela S. Nadell, Professor and Patrick Clendenen Chair in Women’s & Gender History and Director of the Jewish Studies Program, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.