Nicolas Deloche/Godong/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

George Wittemyer, Colorado State University

CC BY-ND

Humans have been over-exploiting African elephants for centuries. More than 2,000 years ago, the Roman Empire’s demand for ivory led to the extinction of genetically distinct elephant populations in northern Africa. But in recent times, population increases among southern African elephants and declines across the rest of the continent have made it hard to clearly assess how threatened the species is overall.

I serve on a team of scientists that recently reviewed African elephants’ status for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). We compiled data from over 400 sites across Africa, spanning 50 years of conservation efforts – and our results were grim.

The number of African savanna elephants – the largest subspecies of elephants – has declined by 60% since 1990. And forest elephants, which the IUCN is treating as a separate species for the first time, have declined in number by over 86%. Based on our assessment, the IUCN has changed its listing from “vulnerable” for all African elephants to “endangered” for savanna elephants and “critically endangered” for forest elephants.

Two species

By separating savanna and forest elephants into independent assessments, our report reveals the critical state of the more elusive forest elephants, which was obscured in previous reviews that lumped all of Africa’s elephants together. Scientific evidence for separating the species has been building over the past two decades, and many taxonomists felt this recognition was long overdue.

Increased research on forest elephants highlights the dramatic declines these secretive giants are undergoing. Studies also show that they are among the slowest-reproducing mammals on the planet. This means that even if they receive adequate protection, their recovery will take decades.

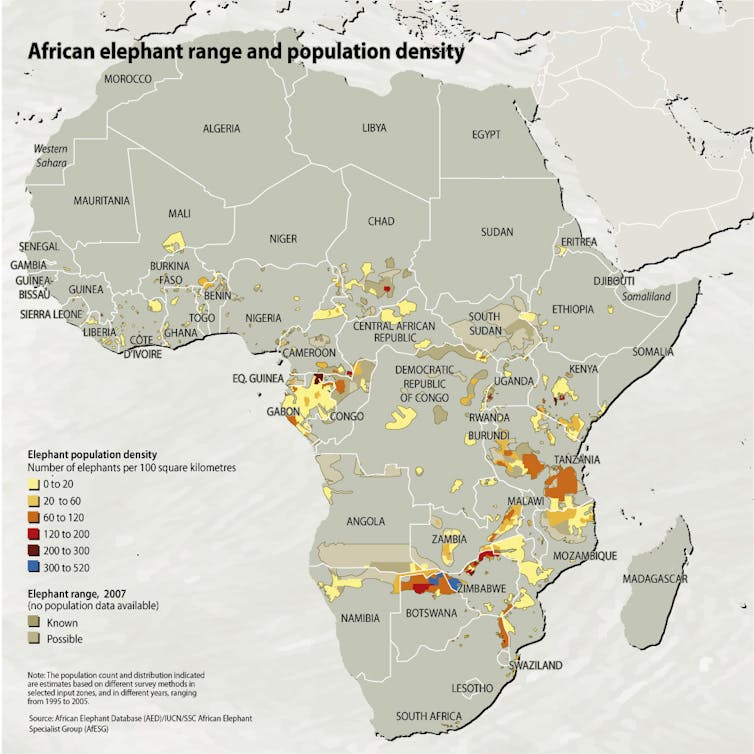

Riccardo Pravetoni for GRID-Arendal/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Global threats, global solutions

Scientists believe that elephant populations across Africa actually increased during the early 20th century, when nations were entrenched in global wars and consumption of ivory and other luxury items declined. After World War II, however, conspicuous consumption surged. Over-hunting for ivory drove severe declines in the number of elephants in the 1970s and 1980s.

Thanks to interconnected global trade networks, along with porous and unregulated borders in many parts of Africa, rising ivory demand in one part of the world quickly translates into higher black market ivory prices in Africa. And these higher prices lead to poaching.

Bernard Dupont/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Removing elephants from an area can pave the way for converting forests and grasslands to agriculture. This cycle has led to the depletion of much of African elephants’ historic range.

Habitat loss also brings elephants and humans closer together, leading to more human-elephant conflict. Such clashes lead to the direct loss of elephants. They also are a burden for local communities that can erode their interest in and support for conservation.

While the scale of decline in Africa’s elephant populations is overwhelming, there are many examples of successful conservation efforts across the continent. The KAZA (Kavango-Zambezi) Transfrontier Conservation effort, anchored by Botswana, holds the largest contiguous elephant population on the continent, and that population has experienced strong growth over the past 50 years. This success reflects government collaboration across borders and work with local communities.

Joint international efforts to reduce the illegal ivory trade are raising awareness of the problems with ivory consumption. China banned domestic ivory trade in 2017, and concurrently ivory poaching across many elephant populations in Africa declined – including in the largest populations in Tanzania and Kenya, which were under severe pressure less than 10 years ago. The core population of forest elephants in Gabon, which declined by 80% between 2004 and 2014, has stabilized with increased government investment and reduced poaching pressure.

Innovative work with communities in countries such as Namibia and Kenya to enhance people’s livelihoods by developing wildlife-supported economies has led to the protection of enormous tracts of lands as conservation areas. And researchers and conservationists are working to find solutions to conflicts between human activities and elephant needs that can be applied across Africa.

By highlighting the precarious state of Africa’s two elephant species, my colleagues and I hope that this Red List Assessment can help motivate African countries with elephant populations and the international community to invest in measures that support elephant conservation.

Elephants provide much more than just aesthetic benefits. Recent studies show forest elephants also play an important role in fighting climate change by enhancing carbon storage in central African forests, among the most important carbon reserves on the planet. The elephants disperse seeds and thin out young trees as they forage, which makes room for larger trees to thrive.

Elephants also are a linchpin of the wildlife-based economy across Africa. And elephants, in compliment with fire, are considered to be ecosystem engineers that structure the balance between trees and grass on Africa’s savannas. Along with many other conservation experts, I see reversing their decline as a global imperative that requires concerted global support.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

George Wittemyer, Associate professor of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.