Several years ago, a relative in Ecuador gave me a beautiful, white, straw hat (below). The hat is so finely and delicately hand woven that it can be rolled up tightly enough that it can almost pass through a wedding ring. Some say it can even hold water, although I have never put mine through that test.

Already in 1869, an article in Scientific American Magazine described such hats, made in Ecuador, as being distinguishable “from all others by consisting only of a single piece, and by their lightness and flexibility.” It also points out that the hats would be equally used in Europe (as in the American continent and the West Indies) were it not for “their high price, varying from two to one hundred and fifty dollars…” The CPI Inflation Calculator says, “$150 in 1869 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $3,401.66 today.”

I don’t remember if my relative called the hat a Montecristi hat, a Jipijapa hat, a Toquilla hat, or just a “sombrero de paja toquilla.” I am pretty sure, however, he did not call it a “Panama Hat,” although it is traditionally yet incorrectly called that.

Let me explain.

As far back as the 16th century, when the Spanish conquistadores arrived in Latin America, natives in the coastal regions of Ecuador were weaving head covers resembling toques (“Tocas” in Spanish), using the dried fibers from a plant abundant in the Ecuadorean lowlands with the scientific name of Cardulovica palmata. The plant came to be locally known as the Toquilla palm plant and, more recently, as the Jipijapa palm. “Toquilla,” the diminutive of “toca,” means little toca or little headdress.

As an interesting sidenote, in the late 18th century botanists gave the tropical plant that Latin name in honor of Spanish King, Carlos IV and his wife Queen María Luisa (“Ludovica’) of Parma, “who promoted the botanical cataloging of South America.”

The weaving of hats became a family occupation in small villages on the slopes of the Andes mountains and along the Ecuadorian coast where the palm plant grows abundantly.

In fact, the Jipijapa palm is named after the small town of Jipijapa in the coastal province of Manabí where many of the great Jipijapa hats are still being made today. They are also made in Montecristi — also in Manabí province — and in the beautiful colonial, Andean city of Cuenca.

Some believe that the famous Ecuadorian hats began to be called “Panama Hats” when, in 1906, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Panama Canal that was under construction at the time.

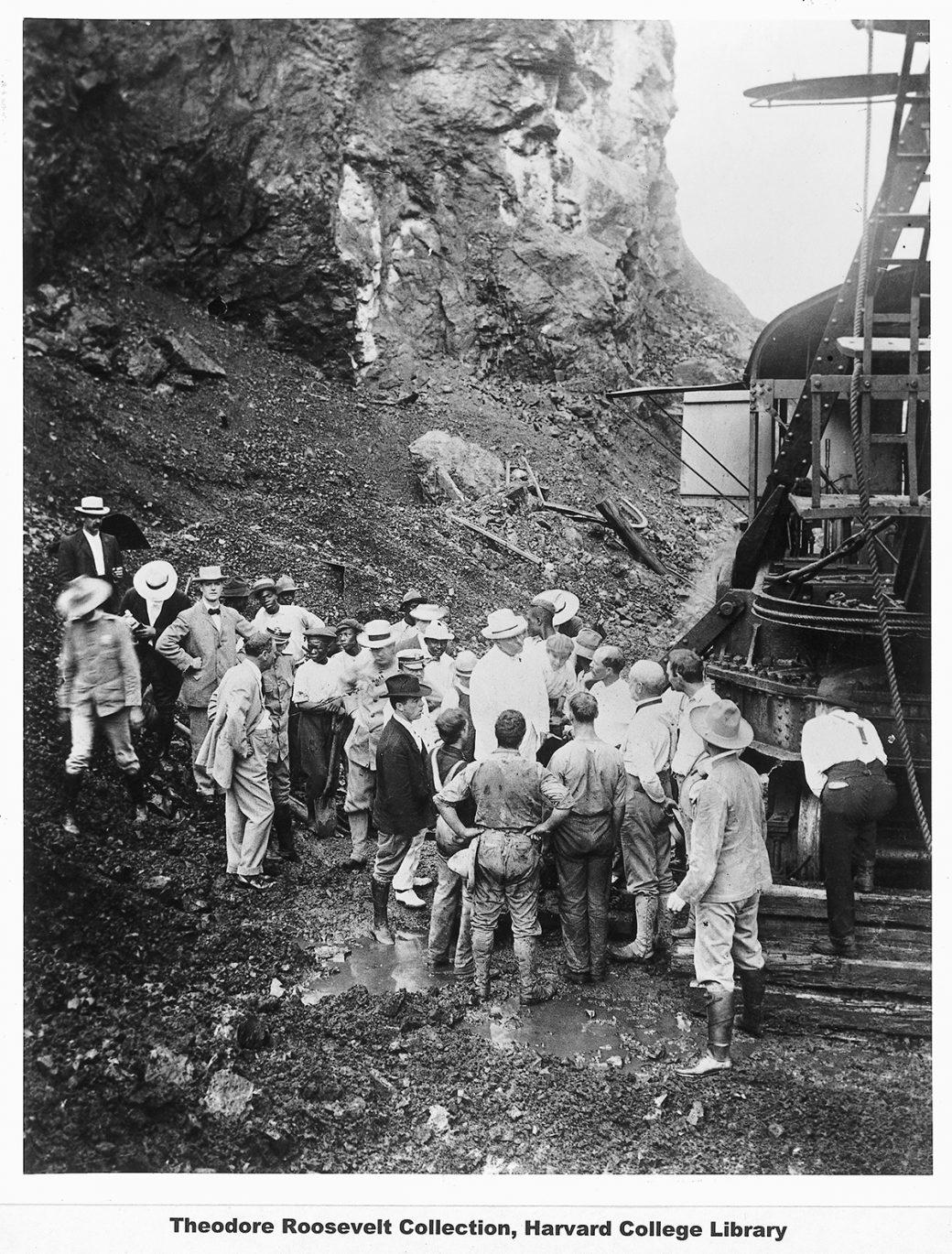

Photos of the president dapperly dressed in a white linen suit and sporting a stylish, white, straw fedora (below) went “viral” (1906 style). Such publicity, on one hand, helped reinforce the perception that the hats originated in Panama, and on the other hand caused the popularity — and the sales – of the Ecuadorian hats to soar.

Credit:Underwood & Underwood, U. & U. (1906).

Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

As can be seen in the photo, “Panama Hats” were already very popular with the workers at the Canal. In fact, Ecuadorian entrepreneurs had been exporting the toquilla hats to and through Panama for nearly a century before Roosevelt’s Panama visit.

In 1835, Manuel Alfaro, a Spanish immigrant, settled in Montecristi, Ecuador, and quickly transformed the artisan, small-town, family toquilla hat-making craft into a thriving business.

Soon, ships loaded with toquilla hats were plying from ports in Ecuador to the Gulf of Panama and beyond, delivering much-needed hats to the thousands of east coast prospectors who were traveling through the hot and humid Isthmus of Panama on their way to California gold rush fortunes.

In 1849, Alfaro shipped over 200,000 hats to Panama, significantly expanding the trade into North America.

Helping his father in the hat business was young José Eloy Alfaro Delgado. Eloy Alfaro would go on to serve as Ecuador’s president from 1895 to 1901 and from 1906 to 1911, becoming “a driving force for fairness, justice and liberty.”

Remember the hat President Roosevelt wore in Panama? It is rumored that the hat was a gift from Manuel Alfaro himself.

Panama hats became even more popular after they appeared at the 1855 Paris World Fair. It probably helped that Napoleon III was presented with a finely woven Panama hat which “His Highness loved…and wore everywhere.”

Soon, the export of toquilla straw hats surpassed Ecuador’s cocoa exports.

In the early 1860s, Ecuador exported 500,000 hats to the United States and Europe.

A little more than three decades later, during the Spanish-American War, the U.S. government bought 50,000 “Panama Hats” for troops based in Panama.

The production and export of the hats gradually expanded until the 1940s, reaching a peak in 1944 when, at 14.8% of total exports, the export of these hats beat cocoa, coffee and banana exports.

To this day, the Panama hat industry (It seems inappropriate to call such a culture, craft and heritage an “industry”) continues to modestly contribute to Ecuador’s economic growth.

Although similar hats are now made in other countries, including in Panama, and although – even in Ecuador – some production has been “modernized,” the Ecuadorian Toquilla hats are still considered the finest and most-sought-after straw hats in the world.

How much does a Panama Hat cost?

One can pay from several hundred to several thousand dollars for a genuine, handmade, quality Toquilla hat, depending on workmanship, quality of materials and authenticity.

Some hats are made in a few days, some in a few months.

Some have as many as 4,000 “weaves” per square inch (“a weave so fine it takes a jeweler’s loupe to count the rows.” ), others a few hundred.

While the quality and price of a Panama hat may vary, there is nothing ephemeral about this Ecuadorian heritage.

In 2012, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognized the traditional weaving of the Ecuadorian toquilla straw hat as “an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.”

Watch an excellent UNESCO video – “Una Historia de Toquilla/A History of Toquilla” – on the making of Panama Hats in Ecuador HERE.