Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Jacob L. Nelson, University of Utah

Journalism faces a credibility crisis. Only 32% of Americans report having “a great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in news reporting – a historical low.

Journalists generally assume that their lack of credibility is a result of what people believe to be reporters’ and editors’ political bias. So they believe the key to improving public trust is to banish any traces of political bias from their reporting.

That explains why newsroom leaders routinely advocate for maintaining “objectivity” as a journalistic value and admonish journalists for sharing their own opinions on social media.

The underlying assumption is straightforward: News organizations are struggling to maintain public trust because journalists keep giving people reasons to distrust the people who bring them the news. Newsroom managers appear to believe that if the public perceives their journalists as politically neutral, objectively minded reporters, they will be more likely to trust – and perhaps even pay for – the journalism they produce.

Yet, a study I recently published with journalism scholars Seth Lewis and Brent Cowley in Journalism, a scholarly publication, suggests this path of distrust stems from an entirely different problem.

Drawing on 34 Zoom-based interviews with adults representing a cross-section of age, political leaning, socioeconomic status and gender, we found that people’s distrust of journalism does not stem from fears of ideological brainwashing. Instead, it stems from assumptions that the news industry as a whole values profits above truth or public service.

The Americans we interviewed believe that news organizations report the news inaccurately not because they want to persuade their audiences to support specific political ideologies, candidates or causes, but rather because they simply want to generate larger audiences — and therefore larger profits.

Mensent Photography/Getty Images

Commercial interests undermine trust

The business of journalism depends primarily on audience attention. News organizations make money from this attention indirectly, by profiting off the advertisements – historically print and broadcast, now increasingly digital – that accompany news stories. They also monetize this attention directly, by charging audiences for subscriptions to their offerings.

Many news organizations pursue revenue models that combine both of these approaches, despite serious concerns about the likelihood of either leading to financial stability.

Although news organizations depend on revenue to survive, journalism as a profession has long maintained a “firewall” between its editorial decisions and business interests. One of journalism’s long-standing values is that journalists should cover whatever they want without worrying about the financial implications for their news organization. NPR’s Ethics Handbook, for example, states that “the purpose of our firewall is to hold in check the influence our funders have over our journalism.”

What does this look like in practice? It means that journalists at the Washington Post should, according to these principles, feel encouraged to pursue investigative reporting into Amazon despite the fact that the newspaper is owned by Amazon founder and executive chairman Jeff Bezos.

While the effectiveness of this firewall in the real world is far from assured, its existence as a principle within the profession suggests that many working journalists pride themselves on following the story wherever it leads, regardless of its financial ramifications for their organization.

Yet despite the importance of this principle to journalists, the people we interviewed seemed unaware of its importance – indeed, its very existence.

Bias toward profits

The people we spoke with tended to assume that news organizations made money primarily through advertising instead of also from subscribers. That led many to believe that news organizations are pressured to pursue large audiences so that they can generate more advertising revenue.

Consequently, many of the people interviewed described journalists as being enlisted in an ongoing, never-ending struggle to capture public attention in an incredibly crowded media environment.

“If you don’t get a certain number of views, you’re not making enough money,” said one of our interviewees, “and then that doesn’t end well for the company.”

People we spoke with tended to agree that journalism is biased, and assumed that such bias exists for profit-oriented rather than strictly ideologically oriented reasons. Some see a convergence in these reasons.

“[Journalists] get money from various support groups that want to see a particular agenda pushed, like George Soros,” said another interviewee. “It’s profits over journalism and over truth.”

Others we spoke with understood that some news organizations depend primarily on their audiences for financial support in the form of subscriptions, donations or memberships. Although these interviewees saw news organizations’ means of generating revenue differently from those who assumed that the money mostly came from advertising, they still described deep distrust toward the news that stemmed from concerns about the news industry’s commercial interests.

“That’s how they make money,” one person said about subscriptions. “They want to entice you with a different version of the news that is not, I personally believe, overall going to be accurate. They get you to pay for that and – poof – you’re a sucker.”

Misplaced concern about bias

In light of these findings, it appears that journalists’ concerns that they must defend themselves against accusations of ideological bias might be misplaced.

Many news organizations have pursued efforts at transparency as an overarching approach to earning public trust, with the implicit goal being to demonstrate that they are doing their work with integrity and free from any ideological bias.

Since 2020, for example, The New York Times has maintained a “Behind the Journalism” page that describes how the newspaper’s reporters and editors approach everything, from when they use anonymous sources to how they confirm breaking crime news and how they are covering the Israel-Hamas War. The Washington Post similarly began maintaining a “Behind the Story” page in 2022.

Yet these displays do not address the chief cause for concern among the people we interviewed: the influence of profit-chasing on journalistic work.

David Livingston/Getty Images

Instead of worrying quite so much about perceptions of journalists’ political biases, it might be more beneficial for newsroom managers to shift their energies to pushing back against perceptions of economic bias.

Perhaps a more effective demonstration of transparency would focus less on how journalists do their jobs and more on how news organizations’ financial concerns are kept separate from evaluations of journalists’ work.

Cable news as a stand-in

The people we interviewed also often appeared to conflate television news with other forms of news production, such as print, digital and radio. And there is ample evidence that television news managers do indeed appear to privilege profits over journalistic integrity.

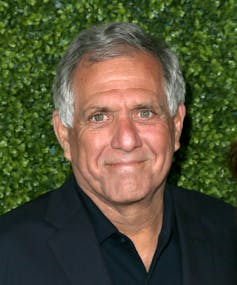

“It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said CBS chairman Leslie Moonves of the massive coverage of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump in 2016. “The money’s rolling in.”

With that in mind, perhaps discussions about improving trust in journalism could begin by acknowledging the extent to which the public’s skepticism toward the media is well-founded – or, at the very least, by more explicitly distinguishing between different kinds of news production.

In short, people are skeptical of the news and distrustful of journalists, not because they think journalists want to brainwash them into voting certain ways, but because they think journalists want to make money off their attention above all else.

For journalists to seriously address the root causes of the public’s distrust in their work, they will need to acknowledge the economic nature of that distrust and reckon with their role in its perpetuation.![]()

Jacob L. Nelson, Associate Professor of Communication, University of Utah

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.