John H. Froehlich via Wikimedia Commons

Robert A. Strong, University of Virginia

When the Supreme Court ruled on March 4, 2024, that former President Donald Trump could appear on state presidential ballots for the 2024 election, it did not address an idea that seemed simple and compelling when Justice Brett Kavanaugh raised it during the Feb. 8, 2024, oral arguments in the case:

“What about the idea that we should think about democracy, think about the right of the people to elect candidates of their choice, of letting the people decide?”

In essence, he was asking whether it would be better to let the people, rather than a court or a state official, decide whether a controversial candidate should return to the White House.

Kavanaugh had a point. Under the Constitution, the people can be – and are – trusted to make a great many important decisions.

But Kavanaugh also missed a key point that I learned in years of teaching about the presidency, the Constitution and impeachment. Right from the very beginning of the nation, and persisting until today, there have been rules that limit the ability of the people to choose their leaders.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787

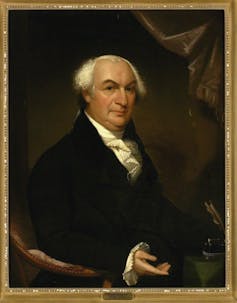

Ezra Ames via Wikimedia Commons

The drafters of the Constitution already had the discussion Kavanaugh was trying to start during the oral arguments.

In July 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention, where the Constitution was written, were discussing impeachment. Gouverneur Morris – a Pennsylvania delegate who wrote the preamble to the Constitution, including its opening phrase, “We the People of the United States” – made an argument Kavanaugh’s question would echo 237 years later.

When discussing whether it should be possible for Congress to remove the president, Morris said no.

The people could decide for themselves, he said. Making the president subject to impeachment, Morris said, “will hold him in such dependence that he will be no check on the Legislature, (nor) a firm guardian of the people and of the public interest.” With regular national elections, Morris said, a flawed chief executive could be removed from office by the voters. Morris added, “In case he should be reelected, that will be sufficient proof of his innocence.”

Dominic W. Boudet after John Hesselius via Wikimedia Commons

But George Mason, a Virginia delegate and slaveholder who championed the idea for the Bill of Rights, was ready with a response. Pointing out that true and fair elections were key to the new nation’s success, Mason noted that if criminal conduct by some future president involved corruption of the election process, the people might have trouble deciding the culprit’s fate in a subsequent election:

“Shall any man be above Justice? Above all shall that man be above it, who can commit the most extensive injustice? … Shall the man who has practised corruption and by that means procured his appointment in the first instance, be suffered to escape punishment, by repeating his guilt?”

Others chimed in with similar replies: Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania; James Madison of Virginia, a future president; Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, a future vice president; and Edmund Randolph of Virginia, a future U.S. attorney general and secretary of state.

The records of the Constitutional Convention say this at the conclusion of that section of debate:

“Mr. Gouverneur Morris’s opinion had been changed by the arguments used in the discussion. … Our Executive was not like a Magistrate having a life interest, much less like one having an hereditary interest in his office. He may be bribed by a greater interest to betray his trust … The Executive ought therefore to be impeachable for treachery; Corrupting his electors, and incapacity.”

The outcome of that discussion resulted in the first of several rules that prevent the American people from choosing just anyone as the president.

Key restrictions

Section 3 of Article 1 of the Constitution is the most direct result of the debate between Morris and Mason. It says that people, including the president, who are impeached and convicted can be barred from office.

Section 1 of Article 2 of the Constitution imposes more limits. It declares that some people simply can’t be president – those not born U.S. citizens, those under age 35 and those who have lived less than 14 years of their lives in the U.S.

Eight decades later, Congress and the states agreed to add a new restriction: Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, says those seeking to hold federal and state offices who have previously taken an oath to support the Constitution may not have attemped to subvert or overthrow the Constitution.

And in 1951, the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, declaring that nobody who had been president for two terms could become president again.

All of these rules stand in the way of simply “letting the people decide,” as Kavanaugh suggested. Strictly speaking, those rules are not democratic. But they are intended to protect democracy itself.

U.S. Senate via Wikimedia Commons

Democracy isn’t always democratic

There are plenty of provisions in the Constitution that run counter to simple democracy.

The Senate and the Electoral College give extra power to states with relatively small populations.

No Congress – even one whose members were each elected by huge majorities – can pass a law abridging freedom of religion or freedom of speech. If a Congress were to pass such a law, the Supreme Court, which has been called the nation’s least democratic branch, could declare it unconstitutional.

Democratic majorities in America are both empowered and constrained by the Constitution. The founders wanted the will of the people to be heard and respected but never given absolute power. Absolute power of any kind was to be checked by a complicated set of prohibitions and procedures.

Kavanaugh was wise to call attention to the fact that in a democracy, the preferences of the people get a high level of deference. Voters certainly can judge the conduct and character of Donald Trump – and many have done so, both favorably and unfavorably.

But George Mason was also right. When politicians corrupt the electoral process, or try to do so, it makes little sense to use elections as the mechanism to fix the problem.

The constitutional provisions for impeachment and the 14th Amendment make clear that people who are found guilty of serious wrongdoing while in office, or violate an oath to support the Constitution, are ineligible to hold high office thereafter. In short, the people can’t choose a Senate-convicted official or an oath-breaking insurrectionist, even if they want to.

America’s Constitution has long acknowledged that the preservation of the republic may, in some cases, require the disqualification of candidates and officeholders who commit crimes while in positions of power or participate in insurrection against the very government they have sworn to serve.

The Supreme Court has sidestepped the question of whether Trump’s actions disqualify him from office and declared instead that Congress must make that determination, under the various constitutional restrictions that continue to exist about who is allowed to serve as president. The practical effect of its decision will be to let the people decide this vital question in the coming presidential election.![]()

Robert A. Strong, Emeritus Professor of Politics, Washington and Lee University; Senior Fellow, Miller Center, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.