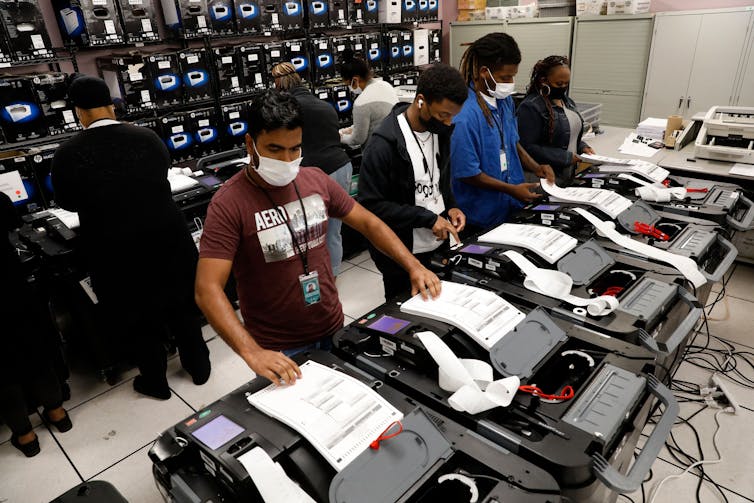

Jeff Kowalsky/AFP via Getty Images

Nicole Kraft, The Ohio State University

The aftershocks of the 2020 presidential election continue to reverberate in politics and the media, building to an crescendo in a high-profile defamation lawsuit.

The trial is slated to begin the week of April 16, 2023, in the case of U.S. Dominion, Inc. v. Fox News Network. The lawsuit rests on whether false claims Fox hosts and their guests made about Dominion’s voting machines after President Joe Biden was elected were defamatory. Dominion is suing Fox for US$1.6 billion.

Fox News hosts said on air that that there were “voting irregularities” with Dominion’s voting machines – while privately saying that such claims were baseless.

The statements have already been proved false. Delaware Superior Court Judge Eric M. Davis ruled on March 31, 2023, that it “is CRYSTAL clear that none of the Statements relating to Dominion about the 2020 election are true.”

The question now is whether the statements harmed Dominion’s reputation enough to rise to the level of defamation.

I am a longtime journalist and journalism professor who teaches the realities and challenges of defamation law as it relates to the news industry. Being accused of defamation is among a journalist’s worst nightmares, but it is far easier to throw around as an accusation than it is to actually prove fault.

Nathan Posner/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Understanding defamation

Defamation happens when someone publishes or publicly broadcasts falsehoods about a person or a corporation in a way that harms their reputation to the point of damage. When the false statements are written, it is legally considered libel. When the falsehoods are spoken or aired on a live TV broadcast, for example, it is called slander.

To be considered defamation, information or claims must be presented as fact and disseminated so others read or see it and must identify the person or business and offer the information with a reckless disregard for the truth.

Defamation plaintiffs can be private, ordinary people who must prove the reporting was done with negligence to win their suit. Public people like celebrities or politicians have a higher burden of proof, which is summed up as actual malice, or overt intention to harm a reputation.

The ultimate defense against defamation is truth, but there are others.

Opinion that is not provable fact is protected, for example.

Neutral reportage – a legal term that means the media reports fairly, if inaccurately, about public figures – can legally protect journalists.

But Davis rejected both of those arguments in the federal Dominion case.

Davis determined Fox aired falsehoods when it allowed Trump supporters to claim on air that Dominion rigged voting machines to increase President Joe Biden’s number of votes. He also said that these actions harmed the Dominion’s reputation.

Proving actual malice

The primary question for the jury will be whether Fox broadcasters knew the statements were false when they aired them. If they did, it would mean they acted with actual malice, the standard required to prove a case of defamation for a public person, entity or figure.

The U.S. Supreme Court established actual malice as a legal criterion of defamation in 1964 when L.B. Sullivan, a police commissioner in Alabama, felt his reputation had been harmed by a civil rights ad run in The New York Times that contained several inaccuracies. Sullivan sued and was awarded $500,000 by a jury. The state Supreme Court affirmed the decision and the Times appealed.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1964 that proof of defamation required evidence that the advertisement creator had serious doubts about the truth of the statement and published it anyway, with the goal to harm the subject’s reputation.

Simply put, the burden of proof shifted from the accused to the accuser.

And that is a hurdle most cannot overcome when claiming defamation.

Why proving defamation is so hard

It is incredibly hard to prove in court that someone set out do harm in publishing facts that are ultimately proved to be untrue.

Most times, falsehoods in a story are the result of insufficient information at the time of reporting.

Sometimes an article’s inaccuracies are the result of bad reporting. Other times the errors are a result of actual negligence.

This happened when Rolling Stone magazine published an article in 2014 about the gang rape of a student at the University of Virginia. It turned out that many parts of the story were not true and not properly vetted by the magazine.

Nicole Eramo, the former associate dean of students at the University of Virginia, sued Rolling Stone, claiming the story false alleged that she knew about and covered up a gang rape at a fraternity on campus. They reached a settlement on the lawsuit in 2017.

Not meeting the malice standard

There are also some recent examples of a defamation lawsuit’s not meeting the actual malice standard.

This includes Alaskan politician Sarah Palin, who sued The New York Times over publication of an editorial in 2017 that erroneously stated her political rhetoric led to a mass shooting. The jury said the information might be inaccurate, but she had not proved actual malice standard.

Long before he was president, Donald Trump had a 2011 libel suit dismissed after a New Jersey appeals court said there was no proof a book author showed actual malice when he cited three unnamed sources who estimated Trump was a millionaire, not a billionaire.

It is so difficult for public figures to meet the actual malice standard and prove defamation that most defamation defendants spend most of their legal preparation time trying to prove they are not actually in the public eye. Their reputations, according to the court, are not as fragile as that of a private person.

Private people must prove only negligence to be successful in a defamation lawsuit. That means that someone did not seriously try to consider whether a statement was true or not before publishing it.

Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Defamation cases that went ahead

Some public figures, however, have prevailed in proving defamation.

American actress Carol Burnett won the first-ever defamation suit against the National Inquirer when a jury decided a 1976 gossip column describing her as intoxicated in a restaurant encounter with former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger was known to be false when it was published.

Most recently, Cardi B won a defamation lawsuit against a celebrity news blogger who posted videos falsely stating the Grammy-winning rapper used cocaine, had herpes and took part in prostitution.

The case of Dominion

Whether Dominion can prove actual malice is up for the jury to decide, but Fox pundits have helped the plaintiff’s case by acknowledging they knew information was false before they aired it and leaving a copious trail of comments such as, “this dominion stuff is total bs.”

Fox’s position is that despite knowing claims made by guests about Dominion were false, the claims were newsworthy.

Does this qualify as actual malice or simply bad journalism?

The decision could send quivers through the political media landscape for years to come.![]()

Nicole Kraft, Associate Professor of Clinical Communication, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.