Victoria Jones/Pool via AP

Laura Beers, American University

When Queen Elizabeth II agreed to suspend Parliament, she gave British Prime Minister Boris Johnson what he wanted.

Opponents of Johnson’s move view it as a cynical and perhaps unconstitutional maneuver. Johnson, they say, is trying to quash growing opposition to his efforts to leave the European Union. Johnson took office July 24, promising to pull the U.K. out of the EU by Oct. 31 even if his government and the European Union hadn’t agreed to terms by then. British voters approved a referendum to leave the EU in June 2016.

The day before Johnson asked the queen to suspend Parliament, opposition leaders announced a plan to force Johnson to ask the EU for an extension to the Halloween deadline, if no deal had yet been struck.

Now they may not get the chance, as a result of Johnson’s actions, and the queen’s. The situation raises thorny questions over who actually represents the will of the British people.

A ‘constitutional outrage’

Speaker of the House John Bercow condemned Johnson’s move as a “constitutional outrage.”

Johnson’s political opponents are already working to challenge the suspension. They have argued that the prime minister’s request to the queen was “both unlawful and unconstitutional” and that the move would have “irreversible legal, constitutional and practical implications for the United Kingdom.”

Johnson’s move was not a complete surprise. In July, former Conservative Prime Minister John Major threatened a legal challenge if Johnson asked for a suspension. Major acknowledged that the queen’s decision could not be challenged, but argued that Johnson’s request could be.

The queen’s power to suspend – or even dismiss – Parliament is unquestioned. The buck stops with her. So why isn’t she taking more criticism for giving Johnson what he wanted?

Constitutional monarchy

One answer is that she had no choice.

That’s the position taken by several British constitutional scholars. Major, too, argued that it would have been “almost inconceivable” for the queen to have defied her prime minister’s request.

Elizabeth is technically the sovereign and free to decide on her own. But the legitimacy of her rule derives from the will of the British people – which is normally assumed to be represented by the elected government. So her independence is actually fairly limited.

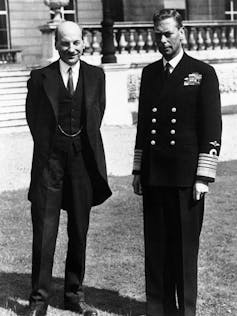

AP Photo

Certainly the queen’s father, King George VI, did not refuse Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s request to suspend Parliament in October 1948, in an effort to ram legal reforms through an obstructionist House of Lords.

That situation is not an exact parallel to current events. Attlee was seeking to override objections from the unelected House of Lords to a bill proposed and passed in the popularly elected House of Commons. Johnson, by contrast, is looking to escape opposition from the people’s elected representatives.

By 1948, there was a general consensus that the real governing power lay with the House of Commons. There were complaints from Attlee’s political opponents, including former Prime Minister Winston Churchill, but nobody suggested George should have refused the request and no attempts to challenge it were made in court.

Parliament or the popular will?

Johnson’s request, by contrast, raises the much thornier question of whether Britain should be governed by Parliament as a whole, or by what one person, the prime minister, says the people want. British opinion on Brexit has always been closely divided, and there have been calls to redo the 2016 referendum that approved it. In addition, Brexit will affect Britain much more – and be harder to amend in the future – than the 1948 legislative changes.

The issue’s importance has led opposition leaders Jeremy Corbyn and Jo Swinson to take the rare step of seeking a personal audience with the queen to present their views. While Elizabeth may hear them out, she has already granted Johnson’s request.

A near-impossible choice

Had the queen refused Johnson, she would have effectively inserted the monarchy into a power struggle between the prime minister and Parliament. That would likely have sparked a greater constitutional crisis – one even bigger than the chaos now erupting in Britain’s political halls.

The last time a monarch went against the advice and requests of elected officials was in 1708, and was justified by worries about a foreign invasion.

Such a dramatic move by Elizabeth now could have been seen as the monarch subverting the government. Instead, she approved Johnson’s request and left to the courts the question of whether Johnson could – or should – have made it.

The queen’s prerogative may be above the law, but the U.K. legal system will decide whether the prime minister can circumvent the country’s elected representatives by claiming to represent the will of the British people.![]()

Laura Beers, Associate Professor of History, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.