Mark Reinstein/MediaPunch /IPX

Paul Manafort, President Donald Trump’s former campaign manager, may be hoping for a presidential pardon.

In September, Manafort pleaded guilty to conspiracy to obstruct justice and conspiracy against the U.S. He also agreed to cooperate with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation. However, Mueller recently filed papers in the federal district court for the District of Columbia alleging that Manafort had violated his cooperation agreement by repeatedly lying to the FBI and to Mueller’s investigators.

In addition, one of Manafort’s lawyers has been repeatedly briefing President Trump’s lawyers about his client’s discussions with the special counsel’s team.

Manafort may have been trying to please two masters in this period by both claiming to cooperate with Mueller, yet at the same time providing Trump with back-channel information about Mueller’s investigation that would benefit him. As a legal scholar, this incident raises a crucial question: Was this Manafort’s play for a pardon?

My research on clemency shows how chief executives have used this power, in particular the power to pardon, to halt criminal prosecutions, sometimes even before they begin.

‘For any reason at all’

The pardoning power, as Founding Father Alexander Hamilton explained, is very broad, applying even to cases of treason against the United States. As Hamilton put it, “The benign prerogative of pardoning should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed.”

Throughout our history, courts have taken a similarly expansive view. In 1977, Florida’s State Supreme Court said that “an executive may grant a pardon for good reasons or bad, or for any reason at all, and his act is final and irrevocable.”

In 1837, the United States Supreme Court held that the president’s pardon power “extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken, or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment.”

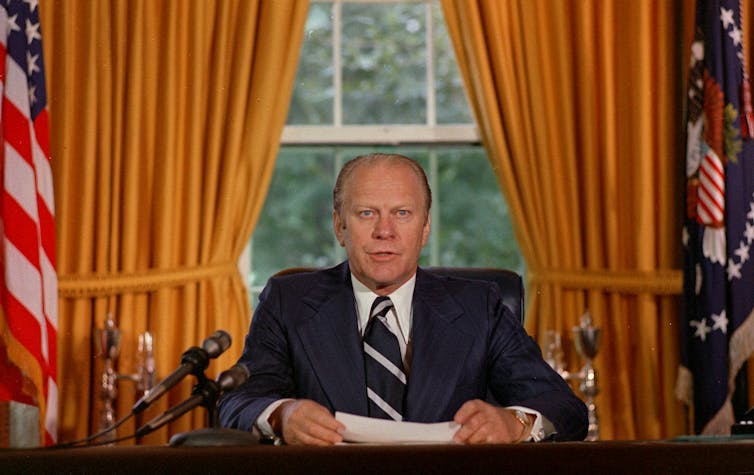

AP Photo

Yet prospective pardons are quite rare. The most famous prospective pardon in American history was granted by President Gerald Ford in September 1974. He pardoned former President Richard Nixon after he was forced to resign in the face of the Watergate scandal. Ford pardoned Nixon for “all offenses against the United States which he … has committed or may have committed or taken part in” between the date of his inauguration in 1969 and his resignation.

In other cases, presidents have halted criminal proceedings immediately after they began. President George H.W. Bush pardoned former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger just after Weinberger had been indicted for lying to Congress about the sale of arms to Iran by the Reagan administration.

Those pardons evoked public outcry against what was perceived to be an arrogant interference with the legal process. Ford’s action may have contributed to his defeat in the 1976 presidential election against Jimmy Carter. And Bush’s pardon of Weinberger prompted accusations that he was engaging in a cover-up. Critics said that his action demonstrated that “powerful people with powerful allies can commit serious crimes in high office – deliberately abusing the public trust without consequence.”

Rule of law

Given such controversies about pardons and the the fear of being labeled soft on crime, presidents until recently have been increasingly reticent about using their clemency power before or after conviction. Thus, while President Nixon granted clemency to more than 36 percent of those who sought it during his eight years in office, the comparable number for George W. Bush was 2 percent. President Obama reversed that trend, granting more pardons and commutations than anyone since Harry Truman.

And President Trump, despite his commitment to being a law-and-order president, already has demonstrated his fondness for the pardon power.

In July 2017 Democratic Congressman Adam Schiff predicted a negative public reaction if Trump granted pardons in the context of the Mueller investigation. He said: “The impressions the country, certainly, would get from that is the president was trying to shield people from liability for telling the truth about what happened in the Russia investigation or Russian contacts.”

With the prospect of a pardon for Manafort in the news, Rep. Jerry Nadler, the incoming Democratic chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, reiterated Schiff’s warning. As he put it, “The President should understand that even dangling a pardon in front of a witness like Manafort is dangerously close to obstruction of justice and would just fortify a claim or a charge of obstruction of justice against the President.”

Trump is seldom dissuaded from his preferred course of action by such warnings and threats. He seems confident that Senate Republicans will provide a firewall against conviction on any impeachment charges. In this context, the prospect of sparing his former campaign chairman any more jail time could provide a plausible cover for “buying” Manafort’s silence with a pardon.

Pardoning Manafort would not only hamper the Russia investigations, it would also deliver another serious blow to American democracy and the rule of law.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on July 19, 2017.![]()

Austin Sarat, Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.