I have often pointed out many of the conservative views of Hillary Clinton, including on foreign policy, civil liberties, and social issues. In a new book, Listen Liberal, Thomas Frank points out how conservative Bill Clinton’s administration was. Salon has some excerpts:

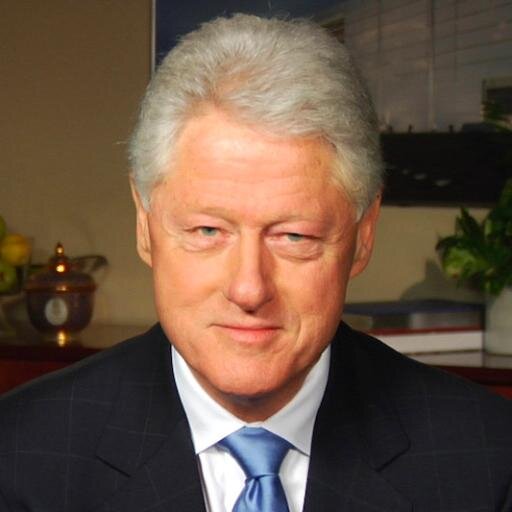

What did Clinton actually do in his eight years on Pennsylvania Avenue? While writing this book, I would periodically ask my liberal friends if they could recall the progressive laws he got passed, the high-minded policies he fought for—you know, the good things Bill Clinton got done while he was president. Why was it, I wondered, that we were supposed to think so highly of him—apart from his obvious personal charm, I mean?

It proved difficult for my libs. People mentioned the obvious things: Clinton once raised the minimum wage and expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit. He balanced the budget. He secured a modest tax increase on the rich. And he did propose a national health program, although it didn’t get very far and was in fact so poorly designed it could be a model of how not to do big policy initiatives.

Other than that, not much. No one could think of any great but hopeless Clintonian stands on principle; after all, this is the guy who once took a poll to decide where to go on vacation. His presidency was all about campaign donations, not personal bravery—he basically rented out the Lincoln Bedroom, for chrissake, and at the end of his time in office he even appeared to sell a presidential pardon…

After the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000, the corporate scandals of the Enron period, and the collapse of the real estate racket, our view of the prosperous Nineties has changed quite a bit. Now we remember that it was Bill Clinton’s administration that deregulated derivatives, that deregulated telecom, and that put our country’s only strong banking laws in the grave. He’s the one who rammed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) through Congress and who taught the world that the way you respond to a recession is by paying off the federal deficit. Mass incarceration and the repeal of welfare, two of Clinton’s other major achievements, are the pillars of the disciplinary state that has made life so miserable for Americans in the lower reaches of society. He would have put a huge dent in Social Security, too, had the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal not stopped him. If we take inequality as our measure, the Clinton administration looks not heroic but odious.

…Someday we will understand that the punitive hysteria of the mid-1990s was not an accident; it was essential to Clintonism. Taken as a whole with NAFTA, with welfare reform, with his plan for privatizing Social Security and, of course, with Clinton’s celebrated lifting of the rules governing banks and telecoms, it all fits perfectly within the new, class-based framework of liberalism. Clinton simply treated different groups of Americans in radically different ways—crushing some in the iron fist of the state, exposing others to ruinous corporate power, while showering the favored stratum with bailouts, deregulation, and a frolicking celebration of Think Different business innovation.

Some got bailouts, others got “zero tolerance.” There was really no contradiction between these things. Lenience and forgiveness and joyous creativity for Wall Street bankers while another group gets a biblical-style beatdown—these things actually fit together quite nicely. Indeed, the ascendance of the first group requires that the second be lowered gradually into hell. When you take Clintonism all together, it makes sense, and the sense it makes has to do with social class. What the poor get is discipline; what the professionals get is endless indulgence.

Of course this is not new information. Howard Zinn described many of the same problems in A People’s History Of The United States, Chapter 23: The Clinton Presidency and the Crisis of Democracy:

Clinton had become the Democratic Party candidate in 1992 with a formula not for social change but for electoral victory: Move the party closer to the center. This meant doing just enough for blacks, women, and working people to keep their support, while trying to win over white conservative voters with a program of toughness on crime and a strong military…

He showed the same timidity in the two appointments he made to the Supreme Court, making sure that Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer would be moderate enough to be acceptable to Republicans as well as to Democrats. He was not willing to fight for a strong liberal to follow in the footsteps of Thurgood Marshall or William Brennan, who had recently left the Court. Breyer and Ginsburg both defended the constitutionality of capital punishment, and upheld drastic restrictions on the use of habeas corpus. Both voted with the most conservative judges on the Court to uphold the “constitutional right” of Boston’s St. Patrick’s Day parade organizers to exclude gay marchers.

In choosing judges for the lower federal courts, Clinton showed himself no more likely to appoint liberals than the Republican Gerald Ford had in the seventies. According to a three-year study published in the Fordham Law Review in early 1996, Clinton’s appointments made “liberal” decisions in less than half their cases. The New York Times noted that, while Reagan and Bush had been willing to fight for judges who would reflect their philosophies, “Mr. Clinton, in contrast, has been quick to drop judicial candidates if there is even a hint of controversy.”

Clinton was eager to show he was “tough” on matters of “law and order.” Running for president in 1992 while still governor of Arkansas, he flew back to Arkansas to oversee the execution of a mentally retarded man on death row. And early in his administration, he and Attorney General Janet Reno approved an FBI attack on a group of religious zealots who were armed and ensconced in a building complex in Waco, Texas. The attack resulted in a fire that swept through the compound, killing at least 86 men, women, and children…

The “Crime Bill” of 1996, which both Republicans and Democrats in Congress voted for overwhelmingly, and which Clinton endorsed with enthusiasm, dealt with the problem of crime by emphasizing punishment, not prevention. It extended the death penalty to a whole range of criminal offenses, and provided $8 billion for the building of new prisons.

All this was to persuade voters that politicians were “tough on crime.” But, as criminologist Todd Clear wrote in the New York Times (“Tougher Is Dumber”) about the new crime bill, harsher sentencing since 1973 had added 1 million people to the prison population, giving the United States the highest rate of incarceration in the world, and yet violent crime continued to increase. “Why,” Clear asked, “do harsh penalties seem to have so little to do with crime?” A crucial reason is that “police and prisons have virtually no effect on the sources of criminal behavior.” He pointed to those sources: “About 70 percent of prisoners in New York State come from eight neighborhoods in New York City. These neighborhoods suffer profound poverty, exclusion, marginalization and despair. All these things nourish crime.”

Those holding political power—whether Clinton or his Republican predecessors—had something in common. They sought to keep their power by diverting the anger of citizens to groups without the resources to defend themselves. As H. L. Mencken, the acerbic social critic of the 1920s, put it: “The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.”

Criminals were among these hobgoblins. Also immigrants, people on “welfare,” and certain governments—Iraq, North Korea, Cuba. By turning attention to them, by inventing or exaggerating their dangers, the failures of the American system could be concealed…

Both major political parties joined to pass legislation, which Clinton then signed, to remove welfare benefits (food stamps, payments to elderly and disabled people) from not only illegal but legal immigrants. By early 1997, letters were going out to close to 1 million legal immigrants, who were poor, old, or disabled, warning them that their food stamps and cash payments would be cut off in a few months unless they became citizens…

The use of force was still central to U.S. foreign policy. Clinton had been in office barely six months when he sent the Air Force to drop bombs on Baghdad, presumably in retaliation for an assassination plot against George Bush on the occasion of the former president’s visit to Kuwait. The evidence for such a plot was very weak, coming as it did from the notoriously corrupt Kuwaiti police. Nevertheless, U.S. planes, claiming to target “Intelligence Headquarters” in the Iraqi capital, bombed a suburban neighborhood, killing at least six people, including a prominent artist and her husband.

Originally posted at Liberal Values