November 11, 2018, will be the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, the (official) end of World War I.

The U.S. World War I Centennial Commission, created by an Act of Congress in 2013, has been working tirelessly to fittingly commemorate that solemn anniversary.

Some of the actions include the establishment of a National World War I Memorial in Washington DC and sponsoring public programs and initiatives such as the 100 Cities / 100 Memorials project to restore World War I memorials across the country.

The commission has also been publishing scores of historical articles and videos honoring the sacrifice of the 116,516 U.S. soldiers who gave their lives in combat and another 200,000 who were wounded during that “forgotten war.”

Aware of the fact that more than 350,000 African Americans served in the U.S. military during that war, despite institutionalized segregation and prejudice, I am awed by the dedication and patriotism of those hundreds of thousands who “chose to support a nation that denied them full citizenship.”

That is why I was fascinated to watch a video shared by the Centennial Commission about “the first African American military pilot to fly in combat.”

Although admirable, it sounds uncomplicated and non-controversial enough.

But wait, there are other “sub-titles”

“The Black War Hero America Didn’t Want”

“Eugene Bullard was the only African American pilot to fly in WWI. But he never flew for the United States.”

The video and the story behind it turn out to be a fascinating look into one man’s journey through personal tragedy (the near lynching of his father) , segregation and racism, perseverance, service abroad, patriotism and heroism, sacrifice (combat injuries), even Jazz and eventually back to America and back to racism, obscurity and poverty.

Please watch the video below, and then read the full story below of “the black hero America didn’t want,” courtesy the World War I Centennial Commission.

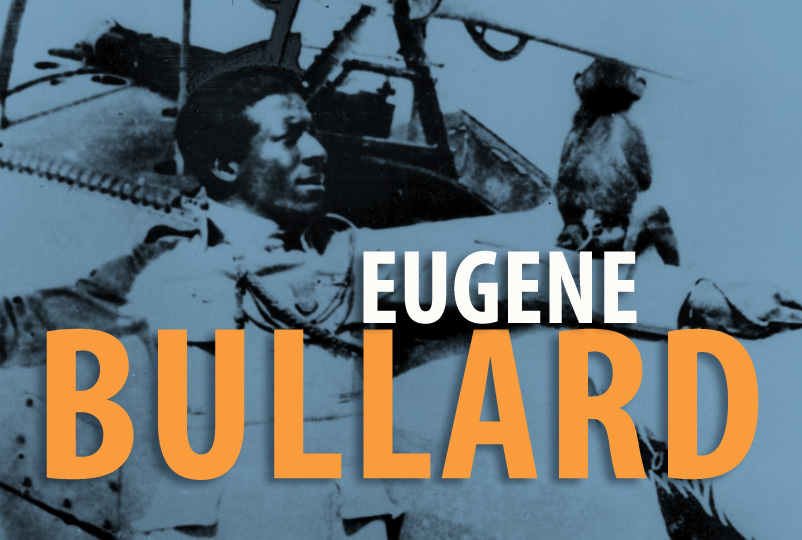

Lead image: U.S. Air Force graphic/Corey Parrish

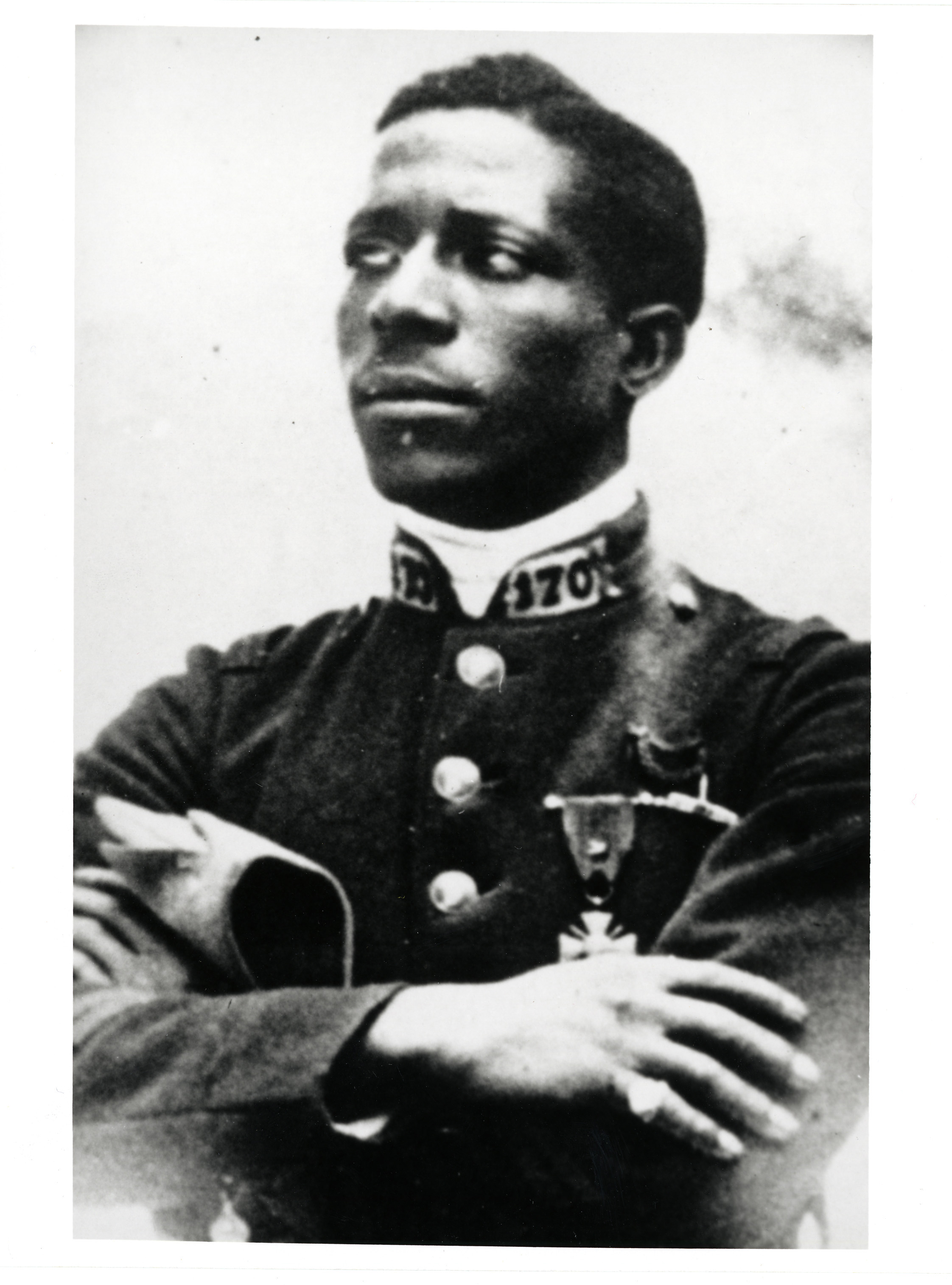

Photo below: U.S. Air Force

~.~

A historical marker commemorates the first African-American aviator from World War I. It reads: “Eugene J. Bullard, 1896-1961. Bullard grew up in a small shotgun style house near this site. His father, William, was a laborer for the W. C. Bradley Company. Eugene completed the fifth grade at the 28th Street School. Shaken by the death of his mother, Josephine, and the near lynching of his father, Bullard left Columbus as a young teenager. In 1912, he stowed-away on a merchant ship out of Norfolk, Virginia. He spent the next 28 years of his life in Europe. Erected by the Historic Columbus Foundation and Historic Chattahoochee Commission 2007”

One of ten children of a black man from Martinique and a Creek Indian mother, he stowed away on a ship to Scotland when a teenager. Settling in Paris, he became a boxer and worked in a music hall. Enlisting at the outbreak of World War I in 1914, as a volunteer from overseas he was assigned to French colonial troops. He saw combat on the Somme front as a machine gunner, and later at Artois and the second Champagne offensive. After heavy losses by the French Foreign Legion, Bullard was allowed to transfer to the 170th Line Infantry Regiment, which eventually was sent to Verdun, where he was seriously wounded in 1916. After recovering, he volunteered that fall for the French Air Service as an air gunner. Following training, he received his pilot’s license in May 1917, and flew with the LaFayette Flying Corps, Escadrille N.93 and N.85, taking part in some twenty combat missions. His reputation grew as the “Black Swallow of Death.”

When the U.S. entered the war, Bullard stood the medical examination to serve in the LaFayette Flying Corps as part of the American Expeditionary Force, but was not accepted, as only white pilots were allowed to serve. He served beyond the Armistice, not being discharged until October 24, 1919, and was awarded the Croix de guerre, among 15 awards from the French government.

Living in Paris between the wars, he worked as a drummer and nightclub manager, eventually owning his own club, gaining famous friends including Louis Armstrong and Langston Hughes. When Germany again invaded France in May 1940, Bullard fled Paris with his two surviving daughters from a marriage which had ended in divorce. Volunteering in defense of Orleans, he was wounded, but escaped to neutral Spain and then went to the United States.

Never fully recovering from his war wound, and finding that his French fame did not follow him home, he worked for a while as an interpreter for Louis Armstrong. With a financial settlement from the destruction of his Paris nightclub in the war, he bought an apartment in Harlem. He was among those attacked and injured during the infamous Peerskill riots of 1949. His final job was as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

In 1954, the French government invited him to participate in the rekindling of the eternal flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe, and in 1959 he was made a knight of the Legion of Honor. Spending his final years in relative obscurity and poverty in New York City, he died in 1961 at age 66. He is buried in the French War Veterans’ section of Flushing Cemetery in Queens, New York.

On August 23, 1994, 33 years after his death, and 77 years to the day after the physical that should have allowed him to fly for his own country, Eugene Bullard was posthumously commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Air Force.