[icopyright one button toolbar]

Sure glad the South lost that war.

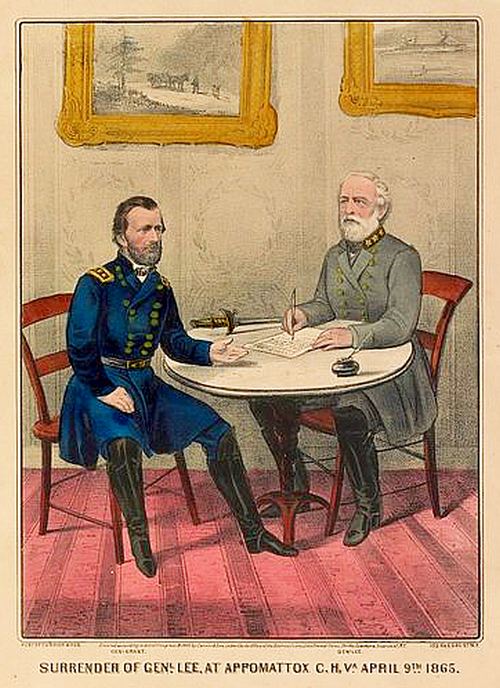

The New York Times remembers that 150 years ago, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Lee Surrendered, But His Lieutenants Kept Fighting

Elizabeth R. Varon / New York Times“If the programme which our people saw set on foot at Appomattox Court-House had been carried out … we would have no disturbance in the South,” testified the former Confederate general (and future senator) John Brown Gordon in 1871.

Well and good. The crux of the article is that Southerners almost immediately began reinterpreting (creatively misinterpreting) the terms of the Appomattox surrender in a manner wholly unintended and carried with it the seeds of the entire historical rewrite known as the “Lost Cause” that still holds large pockets of the South in thrall:

As Reconstruction got underway, former Confederates again and again invoked their interpretation of the Appomattox terms, and particularly the “remain undisturbed” clause, as a shield against social change. Republican efforts to give freedpeople a measure of equality and opportunity and protection were met by white Southern protests that such a radical agenda was a betrayal of the Appomattox agreement — that the prospect of black citizenship, as one Virginia newspaper put it, “molests and disturbs us.”

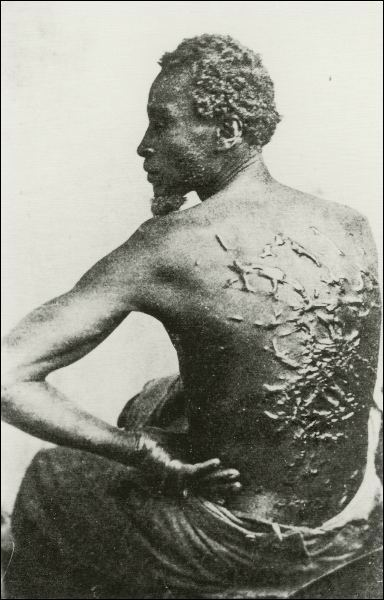

Well, mendacity was always the Southern watchword throughout the entire slavery spectacle. Remember: these were the same folk who interpreted how “beneficial” slavery was to the enslaved.

The benevolence of slavery

But what could and can be expected in a nation that does not remember its past? A quick search of TV listings reveals zero programs on today in commemoration. And only next week, on the anniversary of the assassination of Lincoln does a two part History channel piece on the war take place with multiple repeats. Has this day become so trivial that no remembrance is needed?

Where were the Civil War films? The only two movies I can recall were the dreadful Robert Redford movie attempting to exonerate some of the conspirators in the assassination, and the “third” film in the trilogy that began with the balanced “Gettysburg” and continued with the nearly unwatchable paean to Stonewall Jackson, “Gods and Generals,” the barely-released “Copperhead” recounting the experience of a Maine fellow who wanted to let the South go and thought the war was a bad idea for the North.

That was it.

Tell me that there isn’t a powerful neoConfederate underpinning

to the “patriot,” “tea party” and “libertarian” movements today.

The defining moment in Federalism, the end of slavery, the fundamental shift in American power and politics, all swept under a rug of neoconfederatism, of “libertarianism” — which restates virtually the entire Confederate view of governance minus the minor detail of slavery as long as you ignore that it’s OK, as long as it takes place outside of the territorial sovereignty of the USA — and of a silent, massive attempt to overturn the entire Civil Rights movement that flourished during the centennial anniversary of the war.

Ironically, as voting rights return to functional Jim Crow, and the second amendment has been reinterpreted by the Taney Roberts Court along with a plethora of other absurd, anti-federalist, pro-plutocrat decisions, like Dred Scott Citizens United, Hobby Lobby, etc. etc. so that battlefield weapons (AR-15s) are being carried, increasingly, in open civil society, with a majority of states approving “concealed carry” laws, including, last week, the INSANE law in Kansas that ANYONE can carry a concealed weapon without a permit (or training, or certification of any sort) so that another “Bleeding Kansas” is virtually assured, ironically, this was the moment that Americans MOST needed to remember and relearn the lessons of the first Civil War.

No use crying over spilt blood, I guess.

I do not understand it, but I damn it. I damn it as an American and as the descendant of soldiers who fought in some of the bloodiest battles of that war.

But I do understand how, with a media completely controlled by wealthy plutocrats–whose very wealth depended on slavery–the majority of non-slave-holding Confederate soldiers could have been hoodwinked into fighting to preserve the property of millionaires thinking it to be some greater cause, a/k/a “states’ rights” which was merely a tissue-thin rationalization for the “rights of states to allow slavery” and not about tariffs at all.

Because we have seen the rise of a similar set of lies in our own time.

And so I will remember Appomattox Court House if no one else will.

«o»

After the fall of Richmond, Lee has yet another daring plan (in a long line of daring plans): he will move his army 140 miles south, hook up with Joseph Johnston’s army and strike Sherman’s army in North Carolina. Then they will take to the Blue Ridge mountains, and fight a guerrilla war, seemingly, until the end of time. There is plenty of precedent for this — witness Mosby in the Shenandoah Valley, and Quantrill in Missouri and Kansas (indeed Missouri is almost nothing BUT guerrilla war after the opening years of the war, and “bleeding Kansas” was a guerrilla war for a decade before the Civil War that never really went away). Lincoln himself called what was happening in Missouri the “very visitation of evil.” Today, we’d call it “terrorism.” And that was what Jefferson Davis was calling for, after all.

That was the strategy: recast the war from armies vying with armies to guerrillas taking on the flatfooted armies that they’d hit and run for decades, if needs be.

The tactics were to a) get the troops to rations (which failed at Amelie Court House) and thence to trains down to Danville, Virginia, where the Confederate government had already hied their hences, three miles north of the North Carolina border.

And, as I pointed out previously, logistics did them in. When they needed butter, they got guns. When they had guns, they lost the ammunition.

On the seventh and eighth, after the disaster at Sailor’s Creek, several Confederate generals had held private talks, finally deputizing one of their ranks to broach surrender to Lee. They could all see that they were in a trap, with the bottleneck at Appomattox station, a few miles beyond the “courthouse.”

Lee was not entertaining any notions of surrender. Grant corresponded with him, but Lee, while asking terms, refused to entertain surrender.

He had a plan to get to the Appomattox station and get his army away. He knew that Sheridan had gotten there first — although he may not have known that Custer’s men had torn up the railroad tracks for a few miles below the station. Three trains got away, but four were captured.

Robert E. Lee became part and parcel to

the “Lost Cause” myth after the war, and

has been canonized as a secular saint in

Southern mythology.

After a brutal and chilling night of fitful rest, Lee ordered 9,000 up at 1 am under General Gordon to take the Appomattox station. They knew there were some cavalry there, but had not realized (Lee utterly discounted the notion) that regular troops from Ord’s Army of the James had been marching hard to catch up with the fleeing Rebels and had arrived to back up the cavalry.

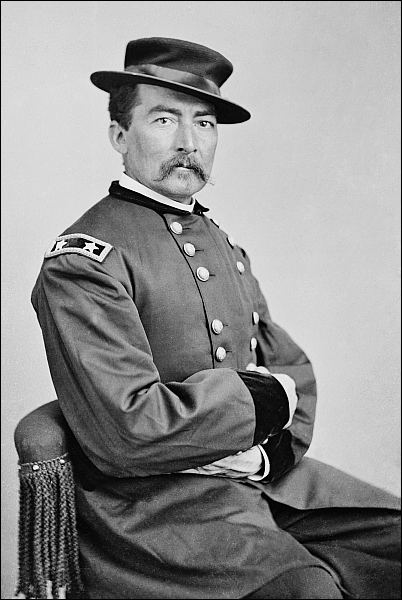

Philip Sheridan’s cavalry was instrumental

in the pursuit and final defeat of the

Army of Northern Virginia

Grant relates this in his memoirs, differing slightly from modern accounts:

Sheridan sent Custer with his division to move south of Appomattox Station, which is about five miles south-west of the Court House, to get west of the trains and destroy the roads to the rear. They got there the night of the 8th, and succeeded partially; but some of the train men had just discovered the movement of our troops and succeeded in running off three of the trains. The other four were held by Custer.

The head of Lee’s column came marching up there on the morning of the 9th, not dreaming, I suppose, that there were any Union soldiers near. The Confederates were surprised to find our cavalry had possession of the trains. However, they were desperate and at once assaulted, hoping to recover them. In the melee that ensued they succeeded in burning one of the trains, but not in getting anything from it. Custer then ordered the other trains run back on the road towards Farmville, and the fight continued.

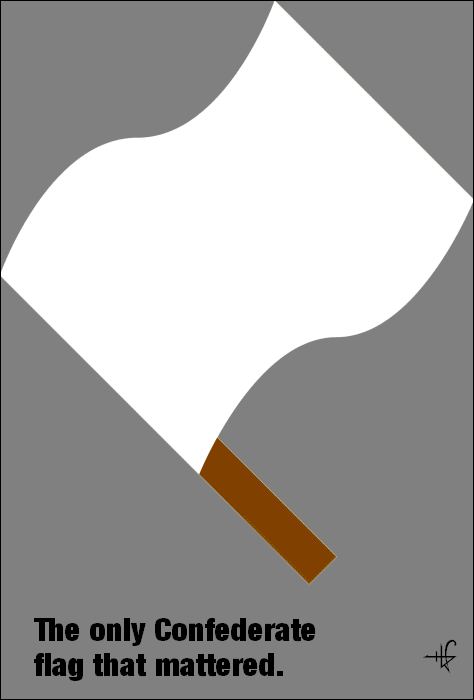

So far, only our cavalry and the advance of Lee’s army were engaged. Soon, however, Lee’s men were brought up from the rear, no doubt expecting they had nothing to meet but our cavalry. But our infantry had pushed forward so rapidly that by the time the enemy got up they found Griffin’s corps and the Army of the James confronting them. A sharp engagement ensued, but Lee quickly set up a white flag.

And, one last time, logistics failed Lee: Longstreet was marching to support Gordon, but his men got stuck behind the supply wagon trains, delaying them beyond any useful time that they might have arrived and altered the outcome. General Grimes attacked and captured one salient, and even messaged Gordon that the road to Lynchburg was now open. The fata morgana shimmered in the early morning light. The daring attack might just work.

And then it all went to hell.

Appomattox Station is at bottom left. Union forces completely cut

Appomattox Station is at bottom left. Union forces completely cut

Lee’s forces off from reaching it. Click to enlarge.

The long and short of it was this: at first, they thought they were driving the cavalry away, like a horse’s tail shooing away flies. Then they saw the union infantry of an army Lee refused to believe was there, and realized that things were hopeless. For all the fooforaw, it was not a particularly bloody affair.

And Lee finally realized that he was irrevocably trapped. There were no more desperate plans. No more daring gambits.

“Well, write a letter to General Grant and ask him to meet me to deal with the question of the surrender of my army,” he reportedly said. And it has been famously reported for many years, “There is nothing left me but to go and see General Grant, and I had rather die a thousand deaths.”

U.S. Grant, as photographed by Matthew Brady

Grant finishes the story:

I proceeded at an early hour in the morning, still suffering with the headache, to get to the head of the column. I was not more than two or three miles from Appomattox Court House at the time, but to go direct I would have to pass through Lee’s army, or a portion of it. I had therefore to move south in order to get upon a road coming up from another direction.

When the white flag was put out by Lee, as already described, I was in this way moving towards Appomattox Court House, and consequently could not be communicated with immediately, and be informed of what Lee had done. Lee, therefore, sent a flag to the rear to advise Meade and one to the front to Sheridan, saying that he had sent a message to me for the purpose of having a meeting to consult about the surrender of his army, and asked for a suspension of hostilities until I could be communicated with. As they had heard nothing of this until the fighting had got to be severe and all going against Lee, both of these commanders hesitated very considerably about suspending hostilities at all. They were afraid it was not in good faith, and we had the Army of Northern Virginia where it could not escape except by some deception. They, however, finally consented to a suspension of hostilities for two hours to give an opportunity of communicating with me in that time, if possible. It was found that, from the route I had taken, they would probably not be able to communicate with me and get an answer back within the time fixed unless the messenger should pass through the rebel lines.Lee, therefore, sent an escort with the officer bearing this message through his lines to me.

April 9, 1865.

GENERAL: I received your note of this morning on the picket-line whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now request an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

R. E. LEE, General.

LIEUTENANT-GENERAL U. S. GRANT

Commanding U. S. Armies.When the officer reached me I was still suffering with the sick headache, but the instant I saw the contents of the note I was cured. I wrote the following note in reply and hastened on:

April 9, 1865.

GENERAL R. E. LEE,

Commanding C. S. Armies.

Your note of this date is but this moment (11.50 A.M.) received, in consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and Lynchburg road to the Farmville and Lynchburg road. I am at this writing about four miles west of Walker’s Church and will push forward to the front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent to me on this road where you wish the interview to take place will meet me.U. S. GRANT,

Lieutenant-General.

And that was it.

Thence came the famous Appomattox Court House scene (along with the irony that it was held in the parlor of a man named Wilmer McLean, who had moved from Bull Run after the first battle, to be away from the war and would supposedly claim “The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor”) which has always been held up as a model of the policy that Lincoln, Grant and Sherman had discussed earlier in the month to be generous to the defeated Confederates, but, as the New York Times piece relates, was immediately distorted by the South into a “negotiation” that Lee held with Grant and the terms of which were “obtained” by Lee, which was later used as an excuse to claim that the North had reneged on its promises (never made) and as a rationalization for continuing to pretend that Blacks had no rights. The very genesis of the “lost cause” in other words.

The site of the surrender

The North felt no need to defend its victory, while a hundred thousand scratching quills succeeded in portraying the Union victory as somehow unfair, their word unkept, their promises (never made) broken, and, ultimately, slandering Ulysses S. Grant as both a general AND a president, the latter libel of which exists to this very day, blaming Grant for a scandal which had taken place under the Johnson Administration, which Grant clearly had no part in.

If you’ve ever tried an alcoholic intervention, multiply that exponentially. The weaseling and lying about the causes and outcomes of the Civil War continues to this very day.

And today, it has been so successful that virtually no one in the plutocrats’ media has a word to say about it.

The Lost Cause today, on its Facebook page

At 3 PM Eastern time, Lee surrendered, and in so doing, did us all an incalculable service: he told his men to go home and be good citizens. For so many Southerners, who saw Robert E. Lee and NOT Jefferson Davis as the personification of the Confederacy, the guerrilla war ceased to exist as an option. A few weeks later, after the assassination of Lincoln, Sherman offered essentially the same general terms to Johnston (as he and Grant discussed with Lincoln) but with Lincoln dead and the radical Republicans in charge, Sherman was not lionized, as Grant had been, for his compassion, but, rather was repudiated and different terms dictated by Congress.

And Sherman’s unfortunate line “forty acres and a mule” was permanently enshrined in the mythology of the “reparations” movement, which continues to this very day.

Either way, for all practical intents and purposes, the Civil War, the Confederacy and the Army of Northern Virginia ended on this day, one hundred and fifty years ago.

Newsworthy?

Lost Cause meme posted today. Still trying to distort history.

Not to our comatose news media.

Or, perhaps, our lapdog news media, who do not want to offend their new masters.

The six companies that control virtually all mass media in the United States of America.

God bless her.

Courage.

This is crossposted from his vorpal sword.

A writer, published author, novelist, literary critic and political observer for a quarter of a quarter-century more than a quarter-century, Hart Williams has lived in the American West for his entire life. Having grown up in Wyoming, Kansas and New Mexico, a survivor of Texas and a veteran of Hollywood, Mr. Williams currently lives in Oregon, along with an astonishing amount of pollen. He has a lively blog, His Vorpal Sword (no spaces) dot com.